Authors: Lichia Saner-Yiu | Raymond Saner

Value from Training: A Requisite Management System ISO 10015 and Its Application

The scope of diplomacy has broadened from traditional state-to-state relations to also include non-state actors (Saner and Yiu, 2003), thereby resulting in a multitude of new challenges for Ministries of Foreign Affairs and traditional diplomats. Learning new skills and acquiring new knowledge is no longer a ‘nice to have’; it has become an absolute necessity for today’s diplomats.

As stated by Kinney (2006), the continued growth and increasing complexity of international and regional diplomatic processes and negotiations requires that more diplomats are given training and provided with learning experiences in the diplomatic tradecraft in the coming decade. A view shared by Rana (2006) who suggests that ‘training is more important than ever for diplomats’.

As most Ministries of Foreign Affairs face budget cuts or frozen budgets, meeting these new challenges through training becomes increasingly difficult, particularly as proper training for effective management is often the first item to be cut from the MFA’s shrinking budget. Hence, proper utilization of scarce training resources is a must, requiring more effective and more efficient management of training processes and training systems.

In the past, the training of diplomats was either outsourced to universities or organized internally within governments through a School of Public Administration, a Diplomatic Academy attached to Ministries of Foreign Affairs, or a training unit within the MFA utilizing external and internal speakers and trainers.

Traditional diplomatic training tends to be academic in orientation and less application-and management-focused, but in today’s dynamic and crisis-prone international arena where new complex problems emerge in sometimes rapid succession and where alliances form, shift, and dissolve quickly, much of the pre-programmed and predominantly history-oriented learning and curricula of traditional diplomatic training no longer ensures the acquisition of new competencies (defined as the ability to apply knowledge, skills, and behaviors in meeting requirements) to fit today’s performance demands of contemporary diplomacy. Diplomatic schools and institutions have not been perceived as responding to these new challenges and work requirements in a timely and apt manner.

WHY CONSIDER QUALITY ASSURANCE?

The need for improving the cost structure for delivering diplomatic training and the need to increase the effectiveness of diplomatic training have become more pressing these days as budgets are being cut, but the demand for training is increasing. At the same time, the customers (MFAs), are demanding greater accountability from the service providers (diplomatic training institutions).

Matteucci (2006) in considering ways and means of enhancing the performance of MFAs, has put forward four major points for adoption by the diplomatic community and the MFAs. These are to:

(a) determine the cost of doing business;

(b) mobilize the know-how about best practices;

(c) establish internal checks and balances;

(d) husband the people in the organization.

While item (d) is the core business of diplomatic training institutions, the other items (a to c) have an indirect bearing on how diplomatic training institutions should manage their own affairs and practices.

In contrast to traditional training ‘administration’, a new approach is needed, based on managing training activities, namely ‘training management’. Training management is designed to make sure that the training results in the acquisition of new and relevant competencies is subsequently applied to the field of work to ensure the improvement of organizational performance of the diplomatic service.

Such a managerial approach to training has to be considered seriously and adopted by the diplomatic community if the service providers want to survive and thrive in these times of great turbulence and partial breakdown of diplomatic processes.

Some diplomatic training institutions have improved their training content and methodology, but most of today’s diplomatic training has not gone far enough and does not yet ensure that the training offered relates to actual performance improvement in our Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Embassies.

On the institutional governance and management front, little has changed. Matteucci suggests (2006) that Quality circles could be adopted which have been used in Japan to mobilize institutional know-how. However, quality circles have their limitations in ensuring a truly comprehensive training quality management system and in delivering the expected results.

High organizational performance depends on high human competence. As Rana (2005) stated: ‘Human talent is the only real resource in a foreign ministry’ (italic added). Hence, the higher the competencies of its employees (diplomats), the higher are the levels of the respective organization’s performance (Jacobs, 2001). According to Noe (2005), training is ‘a planned effort by (an organization) to facilitate employees’ learning of job-related competencies’. Therefore, training should help employees/diplomats to develop competencies which in turn contribute to the organizational performance of their respective MFAs.

The old notion that training is routine business is no longer adequate; instead, quality assurance (QA) should be an integral part of the internal management of diplomatic education and training institutions so that continuous improvement becomes the norm rather than the exception.

TRAINING WITHOUT QUALITY ASSURANCE IS A HIGH-RISK INVESTMENT

Capacity building for training is crucial to ensure the successful performance of diplomats and of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs. However, ministers also need to take into account that training as an instrument for change and improvement often does not provide expected results. Many times, investments in training are not successful and intended objectives through training are not met, leading to disappointments and unhelpful attributions of blame. Worst of all, ineffective training can easily provide the constituencies with a false sense of confidence, thinking that competence deficits have been effectively improved, when in fact the opposite might be the case. Inefficient and ineffective systems of education and in-service training exist in many countries (Saner, Strehl, Yiu, 1997).1The results of our comparative research involving 10 central governments and two provincial governments were published by the International Institute of Administrative Science, Brussels, 1997. However, it would be misleading to look at the education and training sector as if it were a beauty contest. What matters most are the results (skills acquisition, know-how acquisition and increased behavioral competencies of trainees), not output figures (number of trainers, number of training programmes or number of training Centers etc.). At the final end it is the outcome measures, which determine whether or not a given training system is effective or ineffective.

WHAT IS A QUALITY ASSURANCE IN DIPLOMATIC TRAINING?

To be effective, efforts to build individual skills and knowledge must be embedded in an overall framework to ensure that diplomats can apply their new skills on the job, be it at headquarters, or at larger or smaller missions, to improve their performance and productivity in international relations and in regard to the operations of a field office; otherwise, individual competencies might improve, while organizational performance stagnates or declines.

MFAs that want to take advantage of the opportunities offered by the information and telecommunication technologies, for example, do not just need to train a few diplomats on how to use e-mail and search engines to monitor current events. On the contrary, a whole suite of inputs is required, including: (i) skills in public diplomacy in a virtual online environment (e.g. an interactive approach to online communication for the general public, rather than simply putting up a few statements on a website), (ii) performance management (e.g. how to assess productivity and performance results), and (iii) organizational values and norms concerning transparency and the sharing of information.

Quality assurance in this context is about making sure that learning will close reported competence gaps and prepare diplomats for future challenges. It is about ensuring that individual learning will be transferred back to the ministry and will impact the MFA’s overall performance, measured in productivity, quality and impact. Quality assurance therefore requires a management system and involvement of the stakeholders in determining the training needs, selecting the appropriate training modality and approach, and monitoring the delivery of diplomatic training before, during and after the training takes place.

A ‘canned’ diplomatic training program might be sufficient for the general orientation of the new diplomats-to-be, but is no longer sufficient for mid-career and senior diplomats who not only have diplomatic roles and functions, but also perform leadership, supervisory, and managerial roles and functions of a department at an embassy or a consulate. Training programs for these categories of diplomatic personnel require differentiation, tailoring, and context-specific application in order to be

meaningful and effective.

In order to achieve real results, diplomatic training must go beyond an ‘event’ type of approach that focuses on providing short topical seminars or focusing on traditional basic generalist courses. Instead, diplomatic schools and training units within MFAs need to be more closely integrated into the service delivery (or production) of diplomacy and international

relations and involve seasoned diplomats—not only as occasional speakers but also as key partners with regard to the identification of training needs, training design, monitoring, evaluation and post-training support and mentoring. In other words, the full impact of diplomatic training can only be accomplished if there is a learning culture ingrained within the

MFA, if there is line-management involvement, and if there is a diplomatic training function which drives this learning and development process. Otherwise, diplomatic training remains academic, abstract and decoupled from the day-to-day operational challenge of practicing diplomatic tradecraft and managing the MFAs.

WHAT ABOUT THE QUALITY OF TRAINING INVESTMENT?

What quality system could best support a Ministry of Foreign Affairs in improving the efficiency and effectiveness of its SSD training? Different quality standards and instruments are available to measure the quality of training, such as ISO 9000, the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM), or some form of Total Quality Management systems.

Several governments have used either of the three quality instruments mentioned above with mixed results. Some felt these standards were sufficient, others considered the three instruments as being too bureaucratic, too industry-oriented and not sufficiently adjusted to the peculiarities of the training process. A survey of seven countries indicated a trend away from the three traditional quality instruments.

However, none of the quality instruments mentioned address the actual pedagogical process itself, nor the interaction between organizational performance objectives and the training intervention within companies or public organizations.2Raymond Saner; ‘Quality Management in training: generic or sector-specific?’, ISO Management Systems, Geneva, July–August 2002, pp. 53–62.

ISO 10015: THE NEW SOLUTION TO THE QUALITY QUESTION

Realizing the need for more sector-specific guidance for quality assurance of training, a working group was created within ISO to draft a standard for training. Twenty-two country representatives developed the draft text over several years, culminating in the publication of a final official standard ISO 10015 issued by the ISO secretariat in December 1999 (Yiu and Saner, 2005). The new ISO standard offers two main advantages, namely:

a) being based on the process-oriented concepts of the new 9000:2000 ISO family of standards, and hence being easily understandable for administrations already used to ISO-related Quality instruments; and

b) being a sector-specific standard, that is pedagogically oriented, offering MFAs specific guidance in the field of training technology and organizational learning.

What follows is the description of two key features of the new ISO10015 standard.

WHAT IS ISO 10015?

ISO 10015 Quality Standard for Training is one of the QA instruments available that emphasizes stakeholder involvement in defining training needs, uses independent third parties for regular reviews, and focuses on the learning outcome and on-the-job transfer. Therefore, ISO 10015 ensures that the core competencies needed by the MFAs to adapt to the changing environment of world politics and to safeguard a country’s needs and interests are fostered through training.

The ISO 10015 quality standard, available since 2000, offers the most succinct quality assurance criteria for training and continuing education to date and is available for private and public organizations interested in improving their returns on training investment. The main features of the ISO 10015 quality standard for training are illustrated in Figure 1 below.

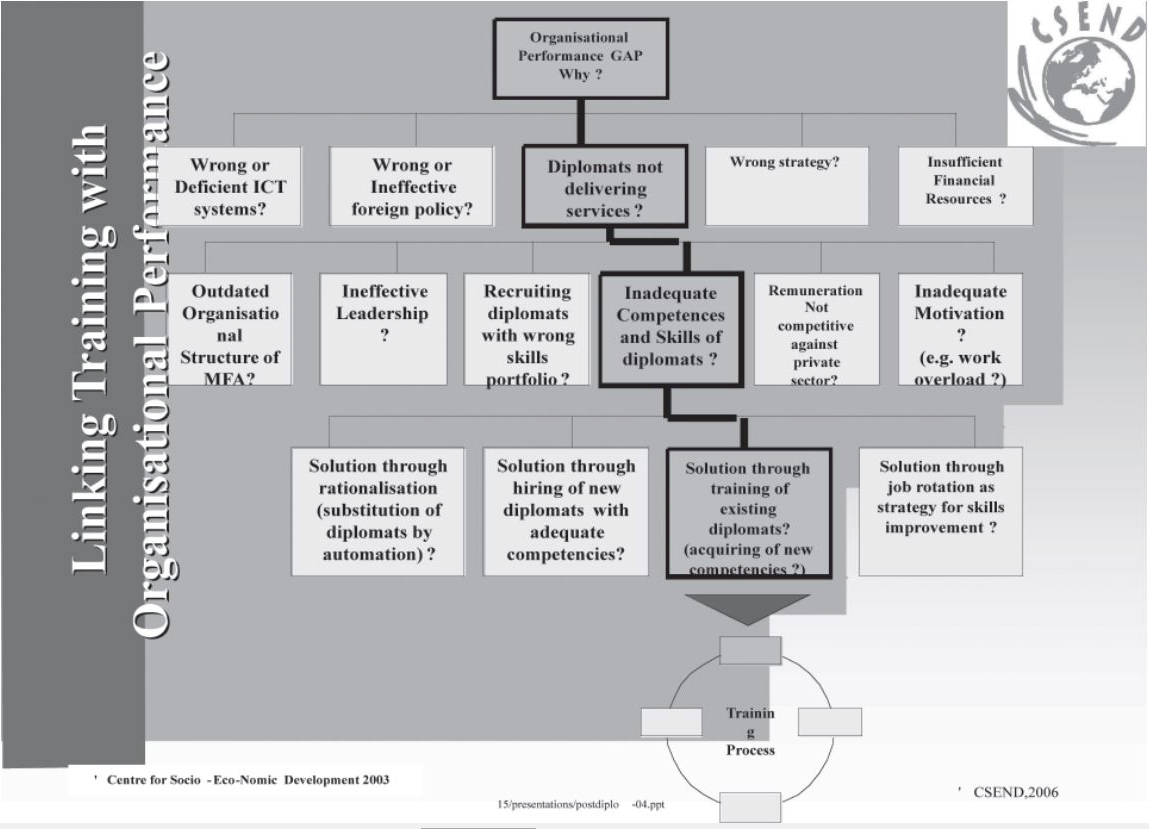

The core elements of an ISO 10015 training management system consist of the following: a decision-making tree (Part A) and a training cycle (Part B). Part A deals with the raison d’être for training (the why) and the competence gaps of MFA staff that impede on the performance of a MFA or a mission; Part B deals with the actual development and implementation of training (the how to).

Looking at the diagnostic tree below (Figure 1), a MFA has to determine first what is the performance challenge that it faces and what are the causes of this challenge. It should ask itself why it is currently not able to reach expected performance goals? Such performance goals could be set for example by a Performance Management System3For performance Management in MFAs, see Rana (2004).—is it because a

MFA is governed by inadequate laws and policies? Or might it be that the new laws and policies are in place but the procedures to apply them are missing? Is the quality of its administrative services poor because the diplomats do not know how to apply them?

If the performance gap is linked to underperforming diplomats, then the Ministry should ask itself, why do our diplomats underperform—is it because their competencies do not fit the job requirements? Are they remunerated below labor market rates and hence are demotivated or ready to switch jobs and move to the private sector? Is the current MFA’s leadership deficient, causing diplomats to feel demotivated? If none of the above is applicable, it might be that their underperformance is due to a lack of skills and/or knowledge. If so, then training would be the right solution.

ISO 10015 in this regard offers a clear road map for guiding a MFA in making sound training investment decisions by asking the top MFA line managers (department heads) to connect training to performance goals and use it as a strategic vehicle for individual and collective performance improvement. As a result, the success of training is not only measured by whether diplomats have improved their personal/individual competence, but also whether diplomats have positively contributed to the Ministry’s organizational performance.

ISO 10015 can help link Part A (organizational performance needs) with Part B (competence acquisition through training). The standard provides a systematic and transparent framework for determining how training programmes can contribute to the overall performance objectives of the organization/institution, while simultaneously identifying whether other interventions are needed (e.g. non-training-based interventions). The training management system thus leads to better design ex ante and delivers data for the continuous improvement of training systems.

ORGANIZING DIPLOMATIC EDUCATION AND TRAINING ON THE BASIS OF PEDAGOGICAL PRINCIPLES AND PROCESSES

Training as an intervention strategy is called for once the MFA has established that the training of current diplomatic staff is the optimal approach to closing the Ministry’s performance gap. Subsequently, the next critical phase for investing in people is that of establishing an appropriate training design and effective learning processes. Diplomatic training needs to be seen as a production process as indicated in Figure 2.

APPLYING ISO 10015 TO EXTERNAL TRAINING PROVIDERS (OUTSIDE OF MFA)

Applied to for instance a Diplomatic Academy or a School of International Relations located outside a MFA (e.g. attached to a university), one can visualize the educational production process in a similar manner as depicted in Figure 2 above but applied to a more formal educational setting where inputs (budget, curriculum etc.) and outputs (e.g. minimum–maximum number of students per year trained) are set by the government’s ministry of education. However, what is often missing in formal higher educational settings is an effective quality assurance system which guides and governs the pedagogical process of academic teaching. In this regard, ISO 10015 could also serve as a management tool to ensure that diplomatic schools conduct their education based on agreed high-quality pedagogical processes as depicted in Figure 3 below.

APPLYING ISO 10015 TO IN-SERVICE DIPLOMATIC TRAINING (WITHIN MFA)

Applied to in-service diplomatic training (training conducted by a unit within the MFA), ISO 10015 offers easy-to-use guidance on how to organize diplomatic training in an efficient and effective manner. Following the well-known Deming Cycle, ISO 10015 defines training as a four-step process, namely, Analyse–Plan–Do–Evaluate. Each step is connected to the next in an input and output relationship (see Figure 4). As a quality management tool, ISO 10015 helps to specify the operational requirements for each step and establishes a procedure to monitor the process. Such a transparent approach enables training management to focus more on the substantive matter of each training investment rather than merely on controlling the expenditure.

Unlike other quality management systems, ISO 10015 helps an organization link training pedagogy to performance objectives and link evaluation with the latter as well. Such a training approach provides an organization with constant feedback regarding its investment in competence development. Similarly, at a higher aggregate level, ISO 10015 offers MFAs the opportunity to examine their training models and to validate their training approaches and operating premises with the use of comprehensive data.

For procurement purposes, ISO 10015 offers practical guidance on how to prepare a training specification plan as the basis for tendering (if required) and for contracting training providers. The same document also provides the framework for training evaluation which goes beyond the ‘happiness scale’ that is commonly used to evaluate training (Kirkpatrick, 1967).

While diplomatic training schools/institutes provide most of the training through their own faculties, a significant portion of their training delivery is actually done by external trainers. These outsourced training activities tend to be either of higher level or of a more technical nature. ISO 10015 can be used to ensure the effective selection of service providers and better ‘fit’ between learning and performance improvement.

POTENTIAL BENEFITS OF AN ISO 10015-BASED DIPLOMATIC TRAINING MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

STRUCTURED APPROACH TO DIPLOMATIC TRAINING INVESTMENT AND UTILIZATION

Instead of leaving it to a diplomat’s own discretion about what to learn and how to ensure continuous self-learning, an ISO 10015 training management system allows the MFA to take a systemic approach in identifying the competence requirements of its key functions and incumbents within the ministry, and in subsequently systematically investing in their competence maintenance and skill enhancement. Instead of treating staff development and diplomatic training as de facto part of the staff benefits, an ISO 10015-based management system can support the MFA in its efforts in ‘reinventing’ itself and in strengthening its institution capability by closely linking the organization’s development needs with the individual learning of its diplomats.

INSTRUCTIONAL SYSTEMS DEVELOPMENT

In addition to the need for effective capacity-building management and quality assurance systems for 21st-century diplomacy, the process of developing instructional systems should be given greater consideration during the design phase of diplomatic training initiatives. Too often, subject matter experts, such as international relations specialists or seasoned diplomats, focus on topical issues of international relations, because this is what they know and are interested in, while overlooking or ignoring institutional and managerial issues that are crucial to ensure sustained and effective outcomes. Subject matter experts (and programs designed and managed by them) tend to undervalue the task of needs assessment and thus fail to consider the full breadth of factors that act to either enhance or inhibit performance.

PROFESSIONAL APPROACH

The adult training literature offers new models for instructional systems design that are more compatible with the real ‘business’ environment (global competition, fragmentation and decentralization of power, non-state actors and fringe groups), utilizing the ‘life case’ method4This can be in the form of a life-case study, or life-case simulation. and other interactive methods to address the changing political context of today’s world. This invariably means that diplomatic training should be seen as contributing to improving the performance of diplomats and performance of the MFAs. Adult training professionals can help subject matter experts design their instructional programs in such a way that they meet the needs of adult learners (e.g. shifting the pedagogy to a more learner-centered, experience-based and interactive approach) and their organizations.

The application of a quality assurance management tool such as ISO 10015 would bring additional benefits. Too often, outdated learning models continue to be deployed in the field of international relations and diplomatic studies. The adoption of ISO 10015-based training quality management systems would encourage diplomatic training schools and institutes and experts/trainers to pay more attention to the impact of their training and hence to adopt appropriate and innovative training methodologies and to ensure a high level of ‘teaching’ competency among instructors.

EXAMPLE OF POSSIBLE APPLICATION TO TRAINING DIPLOMATS IN PUBLIC DIPLOMACY

Based on the performance gap analysis, an MFA could for instance decide to close its diplomat’s performance gap (see Figure 5) with regard to Public Diplomacy by organizing training programs on public diplomacy. The organization of such training programs could for example consist of:

- Concrete definition of training needs for specific target groups;

- Custom-tailored training (and instructional) design and planning for training;

- Providing logistical support for training, actual delivery of training and post-training follow-ups;

- Evaluation of training at different Kirkpatrick levels

CONCLUSION

In light of the rapidly changing and increasingly complex nature of today’s international relations and diplomacy, Ministries of Foreign Affairs need more urgently than ever before to invest in diplomatic training. Only the quality of a Ministry’s human capital can ensure long-term competitive advantage in our knowledge economy and in postmodern diplomacy. In a knowledge-based economy, training is ‘mission critical’ and should not be considered as an activity ‘nice to have’ and therefore dispensable at times of budget cuts or difficulties. Instead, MFAs should aim to ensure resource optimization and greater effectiveness of training investment.

Diplomatic training, as one of the most frequently used approaches to tackle performance issues, needs to be managed carefully like any other major investment. ISO 10015 offers a new and sector-specific quality management tool to ensure the link between the training and organizational performance needs of today’s MFA. It also offers a transparent and easy-to-follow process to ensure a sound and logical link between the four steps of any diplomatic training process and an MFA’s mission and performance requirements—thereby strengthening the expected results of such training investment. The expected outcome of training investment should be two-fold, namely to increase the personal competence of diplomats and a concomitant increase of organizational performance of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Without a structured approach to training and a predictable process for continuous improvement, such expectations cannot be fulfilled.

Select Bibliography

Jacobs, Ronald L., ‘Managing employee competence in global organizations’, in Kidd, J., Li, X., and Richter, F., eds, Maximizing Human Intelligence Development in Asian Business. New York, Palgrave, 2001.

Kinney Smith, Stephanie,‘Developing Diplomats for 2010’, paper given at Diplo Conference on Challenges of Foreign Ministries, Geneva, 2006.

Kirkpatrick, Donald L., ‘Evaluation of Training’, in Training and Development Handbook, New York, McGraw-Hill, 1967.

Matteucci, Aldo, ‘How to survive Budget Cuts—and Thrive’, paper given at Diplo Conference on Challenges of Foreign Ministries, Geneva, 2006.

Noe, Raymond A., Employee Training & Development. Burr Ridge, IL, Irwin McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Rana, Kishan, ‘Performance Management in Foreign Ministries’, Discussion Paper Nr. 93, July 2004, Clingendael Institute of International Relations, The Hague, 2004.

Saner, Raymond and Lichia Yiu, ‘International Economic Diplomacy: Mutations in Post-modern Times’, Discussion Papers in Diplomacy, no. 84, Clingendael Institute of International Relations, The Hague, 2003, pp. 1–37., ‘Die neue ISO 10015: eine Norm für die Aus-und Weiterbildung’, SAS Forum, no. 1, 2003, pp. 22–5.

Saner, Raymond, Franz Strehl, and Lichia Yiu, ‘La Formation Continue Comme un Instrument pour le Changement dans l’Administration Publique.’ Institut International des Sciences Administratives, Bruxelles, 1997.

Yiu, Lichia and Raymond Saner, ‘Does it pay to train?: ISO 10015 assures the quality and return on investment of training’, ISO Management Systems, Geneva (April–May), 2005, pp. 9–13.