The first encounter as a founding moment

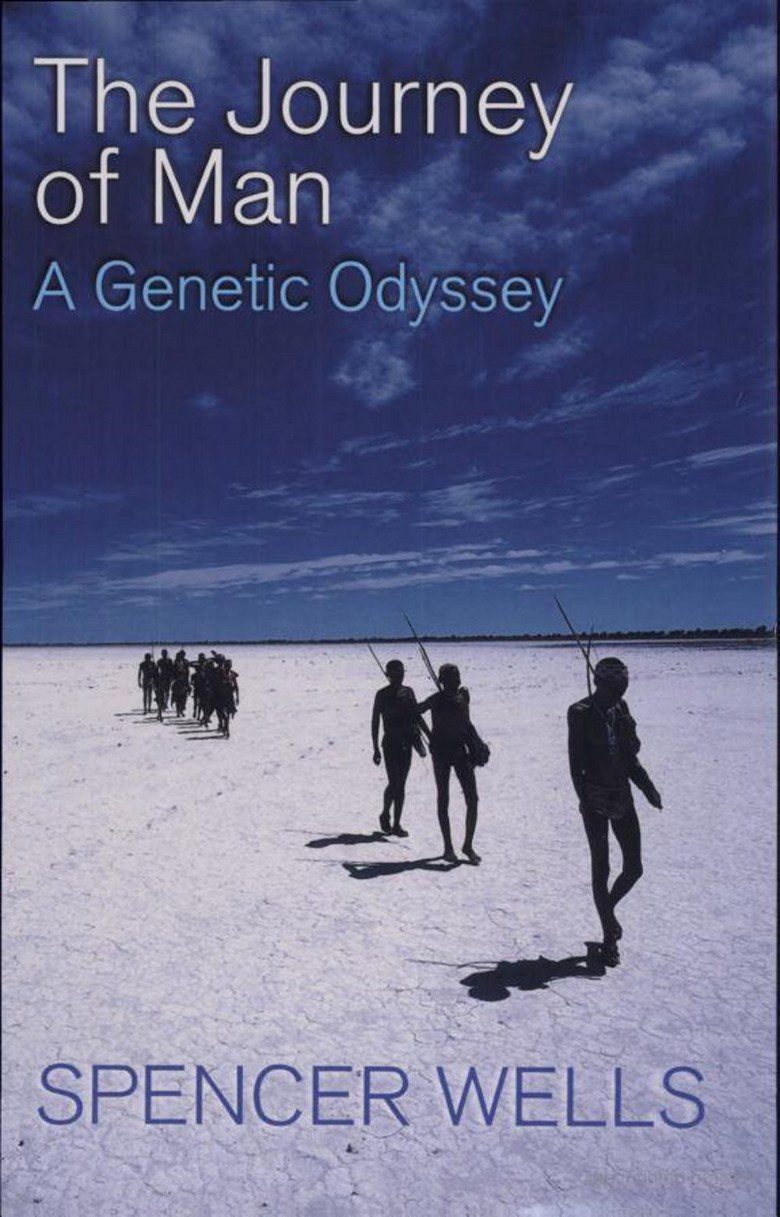

In order to rethink and problematise the origins of what we understand by ‘international relations’, the time has come to take a fresh look at our remote past. Scientific hypotheses about prehistoric life are often built upon fossils, archaeological findings and, thanks to breakthroughs in genetics, DNA analyses. They also stem from either sociological research or ethnographic analogies, prompted by fieldwork observations of extant hunter-gatherer communities and nomadic tribes by present-day anthropologists, such as the Inuit in North America, Australian aboriginal peoples, and African Bushmen from the Kalahari Desert. Fossil evidence and scientific knowledge available to date hint towards the anatomical appearance of Homo sapiens somewhere in Africa, approximately 200-250 000 years ago, in the Middle Palaeolithic. Such an estimate is obviously tentative, as is almost all that can be said about prehistory. This is not the place for a debate on the origin of the human species, that investigation belongs to the realm of evolutionary biology and palaeoanthropology. As the anatomical constitution preceded the symbolic thought, which came into being thousands of years later, the first encounter between two bands, duly recognised as humans by cognitive criteria, could have occurred between 100-150 000 years ago. And if we adopt an even stricter benchmark, full behavioural modernity, including the development of articulate language, our chronological account might well reach up to 40-50 000 BC, already in the Upper Palaeolithic. It is nevertheless conceptually irrelevant (and for all practical purposes impossible) to determine the exact date or place in prehistory for the founding moment we are looking for. Our imagined first encounter does not have to be precisely located in time and space. There is no need to frame it either as ‘before’ or ‘after’. Doing so would be useless and would be bound to contradict the very idea of perennial change in history. More important is the perception that this original interaction launched the underpinnings of the phenomenon called thereafter ‘international’, viewed here in its most elementary form.The primal era of hunter-gatherer bands

Bands, or hordes of hunter-gatherers, are mobile units originating from a nuclear family and based on kinship. They are organised into relatively self-sufficient groups comprising around 25-50 individuals (numbers may vary). Their itinerant life was circumscribed within a loose territory, from which they extracted their daily sustenance by means of hunting prey animals and catching fish, in addition to gathering vegetables, fruits, seeds, roots and anything else fit to be eaten. Fire was used, as well as rudimentary artefacts such as cutting and perforating tools made of bones, wood, stones, and flint (silex). The band was the most basic form of political organisation, the smallest social unit of a stateless society without writing. There was barely any division of labour, rank, or surplus accumulation. The differences were confined above all to age and sex. But having a non-stratified, horizontal, essentially egalitarian social structure did not imply an absolute absence of leaders. Much as in the case of bands of wild apes, where some animals do take the lead, there was an informal, contingent leadership, which derived its strength from particular individual attributes (physical prowess, intelligence, seniority). Authority is believed to have been relatively diffuse. Also, no established procedure was in place for choosing who should formally represent the community as a whole externally. The success of each unit relied upon three essential pillars: resources (all that the environment could provide), organisation (the way individuals coordinated socially to fulfil their potential), and technology (the technical ability to exploit available resources in an organised way). A cooperative lifestyle prevailed most of the time, crucial for the group’s subsistence. Organisation for hunting game, for instance, traditionally depicted as a male task, required a minimum degree of coordination, teamwork, dexterity, and knowledge about the habits of prey. Collaborative sharing within the band also had an important social function, made even more pressing when resources were scarce. Much as with family solidarity, the exchange of goods, information, favours, and services among peers contributed to cementing relationships.Fight or flight, or cooperate?

Back in the Palaeolithic, what might have happened during our mythical original encounter? Could an instinctive reaction of suspicion have triggered impulses of retreat or self-defence? What would the likelihood be of friendly communication that did not end up in violence? Does this interaction have any theoretical significance? In this hypothetical scenario, four particular relationships may be contemplated, with an emphasis on the modalities of non-contact, conflict, cooperation, and subjugation: 1. Absence of relations. Meeting total strangers for the very first time could have been a shocking, terrifying scene. If fear is a feeling that human beings usually experience whenever confronted with the unknown, one cannot completely discard the hypothesis of escape, the most reflexive attitude animals take to protect themselves from situations of real and imminent danger. Such behaviour is much more common when the adversary is considered stronger. If for whatever reason the band left the area or consciously refused to have any sort of contact with the Other, possibly migrating to other lands, a condition of non-relationship may have come to the fore. Withdrawal into indifference and mutual alienation would have been the foreseeable consequence. Isolation in this case would have been an alternative to avoiding or deferring conflict, but at a price: the abandonment of their own habitat to face new challenges in uncharted territories and even risk starvation in the process. 2. Hostile relations. Another instinctive reaction involves putting oneself into a state of alertness for defence and self-preservation. The first face-to-face contact could have been tense, hesitant, and full of distrust and bewilderment. Animosity should be expected if the other side is perceived as an intruder or a competitor. Threatening gestures could have been used as a deterrence mechanism to intimidate or induce submission without resorting to force. In cases of escalation, the outcome could have been a violent showdown, which might have been regarded as a primitive awakening of war. It is useful to bear in mind Quincy Wright’s definition in his book A Study of War: ‘In the broadest sense war is a violent contact of distinct but similar entities’. Hence, a state of war exists when ‘two or more hostile groups’ carry on a conflict by armed force. This minimum definition is compatible with the idea of little-differentiated bands of Homo sapiens clashing in the Palaeolithic, even if only sticks and stones were used to inflict damage on the enemy. 3. Friendly relations. Following the initial hesitation, it cannot be taken for granted that the aftermath would have been necessarily conflictive, violent, or lethal. One may concede that band B was regarded as a threat by band A, but it is a long shot to categorically affirm that the very collective survival of both bands would have been at stake on that early occasion. In other historical first encounters, such as between New World peoples and European conquistadors, there is a record of immediate, friendly contact precisely because, irrespective of any forthcoming tension, the natives did not suspect that the visitors’ intentions might turn contentious or antagonistic. A good-will gesture from band A could consist in offering some object readily at hand. If reciprocated by band B, an ‘exchange of gifts’ would have taken place. This transaction may be understood either as a pioneering modality of intergroup barter (beginning of trade) or as a ‘diplomatic’ exchange avant la lettre, i.e., a manifestation of embryonic protocol that would in the future be associated with customary practices of civility. 4. Merging together. The fourth scenario would be one of subjugation by conquest or assimilation. On occasion, conquest could have culminated in annihilation. Or one of the bands could have merged peacefully with the other. In all these cases, though, the outcome would have led to the disappearance of one of the parties, either physically or as an ‘independent’ entity, which is why this fourth alternative is different from both the second (hostile) and third (friendly) scenarios. In practice, this means that the ‘international’ strictly speaking would have ceased to be present or at best remained in a latent state until further developments affected a change in the relationship status between the parties. In this fortuitous encounter, it cannot be asserted whether the entire bands met one another or whether an advanced team of men, whilst hunting, spotted other men by accident doing the same thing in the same place. If these hunters were the first to engage with each other, a gender-aware observer should ask how far the outcome was affected by the male condition of the parties. That being the case, could the process of socialisation that emphasised force, virility and the protecting role of the male, have stimulated the combative side of the contenders, as a preparation for the fight? It is true that, endowed with reasoning and culture, the predictable reactions of Homo sapiens cannot be reduced to animal instinct. Any communication, albeit non-verbal, would have conveyed, from A to B and vice-versa, their expectations arising out of the interaction. If A initiated an action seen as offensive, B could have emulated the behaviour of A through imitation or mirroring and responded in the same way, eventually creating a mutual negative representation of the roles to be re-enacted later. It is clear that the tit-for-tat strategy is devoid of content as long as the first behaviour is not known. Thus, if a given action from A was regarded as sympathetic by B, a positive dynamic of reciprocal altruism could have emerged, boosted by the promise of shared gains if cooperation-oriented actions were continuously sustained by both parties. Accurately foreseeing which path would have been chosen in any given instance is difficult, if not impossible. Since we will never know for sure what happened (fight, flight, or something else), essential questions requiring investigation are those connected to post-contact developments starting from this ‘year zero’. To what degree would a prehistoric band have been willing to cooperate with strangers, instead of pursuing an isolated trajectory or plunging into physical confrontation? Confidence-building takes much more time than merely unleashing hatred. Throughout this process, however, the emergence of certain negotiating skills would have paved the way for non-violent coexistence.The post-contact period

Assuming the first encounter occurred, relations would have become increasingly imbricated and complex. Over time, the level of external interaction grew, otherness developed, and contact zones between bands spread considerably, apace with the dispersal of the species throughout the planet in the wake of the out-of-Africa migrations. Territorial rivalries may have played a role in driving migratory movements. In keeping with the retreat hypothesis described above in scenario one, some groups could have preferred (or were forced into) isolation, but their numbers tended to fall. Historically, gregarious impulses were paramount, and humans came together to form larger units, from bands to tribes, chiefdoms, city-states, and empires. Foreign relations for prehistoric foragers were not exclusively of a military or warrior nature. Your neighbour is not inescapably your enemy. On the one hand, war could bring tangible benefits: prestige within the group, access to resources, possession of territory, or the capture of women (and later slaves as well). On the other hand, peace also had its advantages: the containment of lethal violence to acceptable limits, lower risk of extermination in the event of defeat, better predictability for activities needed for survival, trade development, and incentives for other exchanges. Under certain conditions, cooperation with other bands could be desirable or even necessary. The higher the frequency of contact with distant groups, the more likely your neighbour could become an ally when resisting attack from hostile bands. In addition to alliances for mutual protection against common enemies, neighbouring bands could also provide mates for procreation, have resources to be exchanged, or even lend assistance in situations of major climatic and environmental adversity. If contacts were friendly, the transmission of ideas, customs, or technical innovations was facilitated in great measure. Symbolic emulation allowed for the imitation of imported behaviours, integrated in due course into the social organisation and daily life of the group. It should come as no surprise that acceptance of outsiders as members of the group, visits, intermarriage, religious ceremonies, celebrations, and other manifestations of organised hospitality became increasingly common. Reciprocity within the groups was vital for their welfare in a challenging natural environment. That same precept spurred the first exchanges between distinct bands, which needed a non-bellicose channel of communication to succeed. The act of cooperating with others presupposes trust, that is, treating strangers in ways usually enjoyed by a family member, relative, or kin-related person. Anthropological studies testify that some isolated indigenous peoples do not see strangers as ‘humans’, thereby making it difficult to treat them as ‘equals’. For some tribes, the Other may be called by degrading names and dubbed savage, barbarian, infidel, vicious, or bestial. The stranger will often arouse fear, hate or contempt, enjoy no rights, have alien customs and unintelligible language. They are either an enemy or a potential threat. Group loyalty hinders the granting of equal status to outsiders. These dynamics lead to the situations of ingroup favouritism and outgroup derogation. For empathy to develop, first the aforementioned obstacles had to be overcome. As a prerequisite for conflict resolution, any negotiation or dialogue could only take place if the Other was acknowledged as a counterpart with rights as well. Their foreignness should not be taken as insurmountable. Before any peaceful exchange, the foreigner/enemy had to be accepted up to a certain point as a potential partner/friend, a transitional process meant to be necessarily gradual. Although elements of a socially-constructed identity contribute to separating one group from another, the internal/external dichotomy does not subsist for long in a pure, ideal-type state. Interaction with the Other changes the group’s perception of itself and its place in the world. The entrenched assumption of order and homogeneity at home becomes untenable in contrast to the prevailing belief of anarchy and heterogeneity abroad. Moreover, as soon as the stranger is no longer unknown, the original distinction between Us and Them begins to fade away. Dissolution, followed by the intermixing of bands, reproductive bonds, exogamy, and other forces of integration, all echoed this paradox: an evolving recognition of differences among larger groups alongside a drive towards amalgamation.Growing amalgamation and webs of relationship

In order to illustrate the scenario of the foreigner-who-becomes-partner transition, one among other possible post-contact developments, it is worth investigating the genesis of diplomacy, a practice normally associated with nation states. According to a recurring view, modern diplomacy had its birth with the exchange of resident ambassadors among the principalities of Renaissance Italy. However, there were certainly much earlier lato sensu diplomatic interactions dating back to antiquity, in Egypt and Mesopotamia, for example. A long, cumulative process of evolution occurred between anthropoids dominated by the instincts of culturally-adaptive, meaning-producing, human beings. If we admit that there were messengers between and across Palaeolithic bands or envoys with specific duties, then the first ‘proto-diplomat’ would have been a band ‘representative’ to whom an informal mission was trusted. He or she would have carried a message to the other party to seek truce, reconciliation, or to deliver warnings and threats. If accompanied by a gift, it could have been interpreted as a signal of peaceful intentions. At times, the same person plausibly performed a number of simultaneous functions (courier, merchant, broker, spy). The preparation, socialisation, and modus operandi, for both hunting and war, were basically the same. Yet negotiation demanded more complex abilities of communication with the other side, only achieved after prolonged maturation. By attributing meaning to existing and abstract things, the development of articulate language expanded the means available for managing conflicts. Likewise, as practical needs preceded symbolic representations in the evolution of prehistoric humans, chances are that the first interaction of a ‘diplomatic’ nature was worked out to settle a concrete question, whatever it was (perhaps a dispute over a large animal or access to water?). Ritual procedures developed subsequently. Over time, protocol became more sophisticated in order to mitigate uncertainty and secure agreements, thus heightening the solemn character of the deal both sides wished to make. A fortiori, in the absence of a writing system, a carefully crafted ritual would properly convey and reinforce the deeper meaning of what had been agreed. To remain viable in the long run, in evolutionary terms, bands had to secure their reproductive capacity by reaching out to other populations. For a tiny group, isolating itself completely could end in demographic suicide. Aiming both at minimising risk and reducing genetic vulnerability, these units set up exchange systems reaching well-beyond their contiguous territories, including information networks to facilitate communication. Against a backdrop of multilevel interconnections and regular communication activity, prehistoric heralds of each unit helped sustain these intergroup networks. Thousands of years later, the Neolithic revolution altered the nature of the hunter-gatherer system. As bands organised into tribes and settled in villages, 10000 years ago, the ‘pre-international’ dynamics changed substantially. The process of population build-up, the advent of agriculture, the domestication of plants and animals, in addition to other technological innovations, led to the appearance of sedentary societies that would displace in importance, but not entirely eclipse, Palaeolithic nomadic bands. Economic, social, and cultural progress had the effect of widening the diplomatic repertoire, based on reciprocity, which now included meaningful advances in communication, formal negotiations conducted by envoys, regular exchange of gifts to signify friendship, more refined peace ceremonies, and the inception of the custom of granting foreign agents some degree of immunity (‘do not kill the messenger’). Such displays of embryonic diplomacy evolved along with the strengthening of socio-cultural contacts among tribes. Their range extended later by means of exogamy, joint religious ritual, pagan festivals, pilgrimage to holy places, trade flows, migration, and expeditions undertaken by missionaries, explorers, and adventurers. Growing imbrication would have eventually resulted in the relative enlargement and reshaping of foreignness, between what belonged to the domestic realm and what was foreign, strange, or different, but which could ideally be transfigured if those ‘outsiders’ had their humanity fully acknowledged. It is not imperative that the Other should be either eradicated or obliterated by sheer assimilation.A final thought

Although sharply differing from the sedentary societies that dominate the present human landscape, the nomadic ‘pre-international’ life of our hunter-gatherer ancestors encompasses a much longer historical period (at least 90% of Homo sapiens history), which might give us a good reason to pay more attention to it in our enquiries about the fundamentals of diplomacy. Bands were never hermetically sealed units operating independently across the planet. But imagining the first-ever encounter works better as a founding myth than picking a date to call it ‘the beginning’. * * *[1] Excerpts from the original article «Back to prehistory: the quest for an alternative IR founding myth», published by Cambridge Review of International Affairs, vol. 31, issue 6, p. 473-493, 2018, available at: https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2018.1539948. See also, by the same author, «The prehistoric origins of international relations», CRIA Views, In the Long Run, 22 December 2018, available at: https://www.inthelongrun.org/criaviews/article/the-prehistoric-origins-of-international-relations. [2] Diplomat, PhD in History of International Relations from the University of Brasilia, currently based in Guinea-Conakry. The views expressed herein are those of the author. Email: egarcia.virtual@gmail.com.