Authors: Lichia Saner-Yiu | Raymond Saner

Organisational culture of UN agencies: The need for diplomats to manage porous boundary phenomena

2004

Diplomats assigned to UN agencies face challenges specific to the UN system. Acting as stakeholders of the UN system and representing member states, these diplomats need to navigate through the complicated UN systems and their various informal arrangements to safeguard the interests of individual member states. At the same time, they need to allow for collaboration to deal with interdependent needs, such as preventive diplomacy 1this concept was first put forward by Butros Butros-Ghali in his Agenda for Peace to the Security Council in 1992 as a more effective approach for the UN to mediate humanitarian crises, trade, public health, humanitarian assistance, peacekeeping, environment, and development cooperation. Besides having to face intercultural complexity in their exchanges with UN staff coming from almost all possible cultural backgrounds, diplomats also need to understand the different organisational cultures of UN agencies, which are distinct and not comparable with those of any other private or public sector organisations.

The goal of this article is to introduce readers to the complexity of the organisational culture of UN agencies to limit possible misunderstandings about the functioning of the UN and its agencies and to make diplomatic interactions with UN agencies as efficient and effective as possible. Indirectly, it is hoped that this article may also contribute, however slightly, to the successful functioning of the UN community and offer support for the mutually beneficial collaboration of nations and the identification of successful solutions to meet shared global concerns.

United Nations: The Context

In September 2002, the UN system consisted of 191 member states. It includes six core bodies: the General Assembly, the UN Secretariat, the Security Council, the Economic and Social Council, the Trusteeship Council, and the International Court of Justice. In addition, the UN system has 14 specialised agencies and 12 funds and programmes. Collectively, of about 56,000 staff members, some 22,000 occupy professional positions in the UN workforce.2Freedom Alliance Exposes UN Hiring Practices: UN Commissars Continue Anti-American Bias in Staffing UN Jobs, Fred Gedrich, Freedom Alliance Issue Brief 2001-07 (September 2001), The 15 UN organisations apply a common system of salaries and pensions 3UN Personnel Policies Support World Body’s Unique Organizational Values, Terry Slater, Public Personnel Management 21.3 (Fall 1992), 383-384. (excluding the WB, IDA, IFC, and IMF) and employ people assigned to over 170 countries, working at some 600 different places throughout the world and using six major official languages. Some 52% of UN staff work for the UN Secretariat and its programmes. The remaining 48% are employed by the 14 specialised or related agencies, including the ILO, FAO, UNESCO, UNIDO, WHO, World Bank, IDA, IFC, IMF, ICAO, UPU, ITU, WMO, IMCO, WIPO, and IFAD. These agencies report annually to the Economic and Social Council in New York.

These intergovernmental agencies are separate, autonomous organisations related to the UN by special agreements. They collaborate with the UN and with each other through the coordinating machinery of the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Their secretariats, composed of international staff representing over 170 different nationalities, work under the direction of the executive head of the respective agencies. They provide either a forum for negotiations and decisions (e.g., international conventions regarding trade, labour, and human rights) or specific services (e.g., health, institution building, and agricultural development).

The Charter describes the Secretary General as “Chief Administrative Officer” of the Organisation, who shall act in that capacity and perform “such other functions as are entrusted” to him/her by the Security Council, General Assembly, ECOSOC, and other UN organs. The UN Charter also empowers the Secretary General to “bring to the attention of the Security Council any matters which in his opinion may threaten the maintenance of international peace and security.” These guidelines both define the power of the Secretary General’s office and its scope of action.

However, the interpretation of the role of the Secretary General is very much dependent on the incumbent of the office. It ranges from administration to a more dynamic and innovative role. The current Secretary General, for example, sees himself assuming a combined role with equal parts assigned to being a diplomat and an advocate, a civil servant and a CEO, and being a symbol of United Nations ideals and a spokesman for the interest of the world’s peoples, in particular the poor and the vulnerable among them.4The Role of the Secretary General. United Nations, UN Department of Public Information (2000) [website]; available at https://www.un.org/News/ossg/sg/pages/sg_office.html. In the different perceptions of the role and responsibility of the Secretary General lays another source of potential tension between the Organisation, the Security Council, and the General Assembly.

Criticism and On-Going Reform

In this world of renewed and growing conflicts, some countries express misgivings about the role of the UN and, in particular, of its Security Council. Disagreements heightened between key countries before the invasion of Iraq by the USA and its allies. In particular, the functioning of the Security Council was severely criticised and the future of the UN was put into question by some leading officials of the US government who expressed unhappiness about the multilateral decision-making process in general and the accompanying rules and conventions in particular.

Leaving the Iraq war and the related conflict between key counties aside, few would want to abolish the very existence of the UN system with all its many specialised agencies and accompanying multilateral treaties. Most countries prefer the multilateral UN system with all its imperfections to a situation based on unilateral dominance or bilateral confrontations. It is up to the member countries that exercise oversight and governance over the UN system to make it work to the benefit of the total membership.

While the large majority of the current UN membership prefers continuity of multilateralism, many countries nevertheless have expressed their wish to see efficiency and effectiveness improved within the UN system. Criticism and concerns have been raised regarding various perceived shortcomings of the UN system and its ineffective performance, especially when dealing with humanitarian crises and inter-racial/communal armed conflicts.5Secretary General Kofi Annan would be the first to acknowledge that the UN failed to respond effectively to some of the recent atrocities in places such as Rwanda (1994) or Bosnia (1995). He published two tough reports on the Srebrenica and Rwanda massacres with forthright frankness. Besides acknowledging the responsibility of the UN Peacekeeping Department, these reports also implicated the Security Council in its woeful lack of quick and active responses to clear signs that horrendous catastrophes were in the making. Criticism of some agencies has been raised in regard to lack of reform of swollen bureaucracies, tardiness in responding to the needs in the field 6United Nations: Challenge for the New Boss, Time, 3 February 1992, 28-29., and the even more grave accusation of fraud and abuse 7U.S. Policy and U.N. Reform: Past, Present, and Future, Zarrin Caldwell, [website]; available at https://www.unausa.org/publications/reformfs.asp. within some specialised agencies.

Reform of the UN system has been an ongoing process since the 1980s, focusing on budgetary, management, or structural issues. The US in particular, and other Western industrialised countries have pushed for budgetary and management reforms with visible success while the more complicated institutional changes remain limited and harder to accomplish.

Faced with the uncertainty induced by the attacks on the World Trade Towers (9/11/2001), the Iraq War, and the twin processes of global integration and local fragmentation, the UN role of offering global governance structures and facilitating social and economic development around the world has become more important than ever before. Yet, without a mandate to regulate world affairs and with no control of independent resources, the UN’s capacity to intervene, especially during times of crisis, remains rather limited.

In the words of the Secretary General, Kofi Annan, “if the UN is to effectively realize its global mission of furthering peace, development, and human rights, it must manage its human resources better.” He further stated, “We are too complicated and too slow. We are over-administered and have too many rules and too many regulations.” Calling for more investment in staff, simpler procedures, and more authority for managers, the Secretary General said that the reforms he proposed were designed to ensure that the UN could have “the right people with the right skills in the right job at the right time.”8Human Resource Management Reform: Report of the Secretary General, United Nations (A/53/414/1998), United Nations General Assembly, New York, 13 October 1998.

What was omitted is that the complex operational environment of the UN system is embedded in a situation of divergent interests, power blocks, complicated interaction patterns, and contrasting worldviews. The UN is not only a system of service providers but, at times, is called upon to be an arbitrator between competing factions without vested power to do so. Diplomats representing member countries have an important role to play to support the Secretary General in achieving the challenging goals of strengthening the capacity to perform and, in addition, in co-creating an enabling environment for the UN to carry out its duties.

The Organisational Culture of the UN

Multilayers of Political Influence

Public management and public organisations are characterised by features distinct from those of private sector companies. Rainey summarises the commonly known aspects, namely: reliance on governmental appropriations for financial resources, presence of intensive, formal legal constraints, presence of intensive external political influences, and greater goal ambiguity, multiplicity, and conflict.9Understanding and Managing Public Organizations, Hal Rainey, Jossey-Bass, 1991, 33.

The UN system functions with similar characteristics. Each specialised UN agency has its own decision-making body involving a multitude of government and related constituencies; together they approve annual budgets and influence the major directions of the agencies’ programmes and activities. Hence, the decision-making process can be very complex and presents in itself major obstacles regarding clarity of purpose, effectiveness and efficiency of management, and unity of staff.10Decision-Making in the International Civil Aviation Organization: Politics, Processes and Personalities, Eugene Sochor, International Review of Administrative Sciences 55 (1989), 241-259.) $(The Politics, Power and Pathologies of International Organizations, Michael Barnett and Martha Finnemore, International Organization 53.4 (Autumn 1999), 699-732. These constraints are even more pronounced within the workings of the UN Secretariat which negotiates and deals with international “political” dossiers.

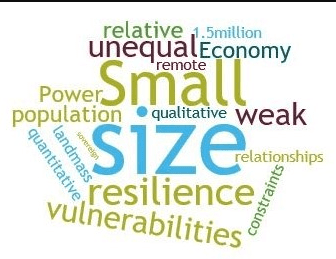

The budgetary process determines the resource allocation to different programmes; hence, member states have keen interest in influencing the outcome through different forms of manoeuvring. Alliance-building within the diplomatic communities and within the UN secretariat and agencies becomes critical, especially for the small nations that rely on UN appropriation for their national development.

At the personnel level, UN staff members, bound by the UN rule of neutrality11As international civil servants, staff members and the Secretary General answer to the UN alone for their activities and take an oath not to seek or receive instructions from any government or outside authority. In addition, under the Charter each member state undertakes to refrain from seeking to influence the staff and the Secretary General improperly in the discharge of their duties., are supposed to stay above the political manoeuvring. However, this has not always been the case. Mixed loyalties toward the UN system and one’s own home country are almost inevitable since many member countries influence their own nationals’ posting within the UN system and promote their career paths. However, personal and national interests alone cannot fully explain why the UN is a complex system with sub-optimal performance. Additional understanding is needed to find ways to strengthen this important institution.

At the organisational level, the UN system is constantly under pressure to fulfil the wishes of its paymasters and constituencies. Sandwiched between the Security Council (akin to a cabinet of nations led by the five permanent members) and the member states (shareholders), the Secretariat and the UN system are evaluated based on both the political criteria and actual performance in discharging its responsibilities. International politics are played out in the UN arena. As a result, mirroring its membership, at times of crisis the UN is locked up by policy paralysis and power struggle. Diplomats inadvertently become part of the problem when executing the national will at the expense of collaboration for common good.

At the grassroots level, non-state actors have been allowed, albeit gingerly, into the international policy arena of the UN. Increasingly vocal and self-assured, trans-national NGOs and other self-styled militant groups have yielded considerable influence on international policy, at times even greater than some of the member states. They promote their agendas through active participation in the UN system and by providing service delivery for development and/or humanitarian purposes.12The rising public policy and diplomatic role of transnational NGOs has been discussed by Raymond Saner and Lichia Yiu in International Economic Diplomacy: Mutations in Post-Modern Times, Discussion Papers in Diplomacy, No. 84 (January 2003), Netherlands Institute of International Relations, Clingendael, The Hague.) This third sector, representing trans-border and communal/grassroots interests, has enlivened international policy debates, but also added to the already complex process of the multilateral decision-making process. Diplomats, as well as UN officials, are pushed to recognise the legitimacy of non-state actors in their so-to-speak “home turf” and to learn how to live with such post-modern reality.

Internal Fragmentation and Coordination Barriers

Internally, for decades the UN system has had coordination difficulties. For instance, UN agencies may compete with each other to be given specific mandates 13The current Doha Round of the WTO requires capacity-building for least developed countries. Despite ample attempts to coordinate programmes, the World Bank, UNDP and UNCTAD remain insufficiently coordinated, to the detriment of the LDCs. or they have overlapping mandates and opt not to cooperate as they should.14A case in point here was the fight between the ILO and UNICEF regarding child labour. Overlapping and competing programmes among different agencies remains a reality despite best efforts to eliminate such wastefulness over the last twenty years. However, this sub-optimal performance of the UN should be attributed not only to structural origins but should also be understood from an organisational behaviour perspective.

Inter-agency coordination has been difficult because of low system cohesion within the UN family, resulting in mini-kingdoms and/or serfdoms. Layers of “class or prestige”15Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling and Controlling, Harold Kerzner, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1979. create gaps between various levels of management. In addition, functional gaps sometimes exist between working units of UN agencies. If horizontally layered management gaps are superimposed on vertical functional gaps, so-called “operational islands” can emerge which refuse to communicate with one another for fear that giving up information may strengthen their “opponents” and reduce their own power base. Duplication of functions and programmes is but one manifestation of this internal fragmentation.

Similar rifts may exist at the intra-organisational level. Management control is insufficient to harness a more cohesive culture and operations. Many UN agencies have neither a functioning performance appraisal system nor career plans or merit system. Depending on power shifts, managers are reassigned to posts without necessarily possessing the required professional expertise. On the other hand, UN agencies cannot easily dismiss their staff. Hence, a strong conflict exists between relative job security and a sense of insecurity based on persistent uncertainty regarding job posting and career prospects. Both factors combined encourage patronage, which, in turn, reinforces the multicultural divisions within the staff of UN agencies, which, in turn, reinforces “patronage-tribalism” and exacerbates the problem of coordination further.

Individual “fiefdoms” have also been prone to curry favour with specific constituencies. Such alliance-building, on the one hand, consolidates one’s hold on power; on the other, it further erodes the already permeable boundary of the UN system.

Weak and Porous Organisational Boundaries

Continuous external pressures on financial and political decisions in conjunction with complex decision-making processes and the entrance of non-conventional actors weaken organisational boundaries and open UN agencies to the power plays of multiple external and internal constituencies. To understand this phenomenon, Henry Mintzberg developed a typology of configurations of organisational power. He proposed one possible relationship between external and internal coalitions that, the authors believe, fits the context of the UN system well. He very concisely stated: “A divided external coalition encourages the rise of politicised internal coalitions, and vice versa.”17Power and Organisation Life Cycles, Henry Mintzberg, Academy of Management Review 9.2 (1984), 207-224.

The board members of UN agencies, namely the various member governments, have been and continue to be divided over general as well as particular issues. The most apparent divisions occurred during the cold war period. The current divisions centre on the North-South divide, trade block conflicts, and on particular issue-by-issue conflicts, whatever is at stake at the particular moment for the governments concerned.

Member governments exert pressures on the leading heads of UN agencies and vice versa. The respective director generals use their political weapons to counterattack real or perceived threats to their power and re-election. De Cooker, who cites various secondary sources, gives an example of such manoeuvres:

Mr. Saoma, the head of FAO is accused of having politicized and mismanaged his organisation, of practising coercive and terrorist tactics and to run a reign of terror in the secretariat … In addition to the US, the UK, Australia and Canada have suspended further payments to the organisation pending budget reforms. These countries are applying financial blackmail to the organisation, in order to obtain the right to approve or veto its budget level.18Law and Management Practices in International Organizations, Chris De Cooker, Martinus Nijhoff and UNITAR, 1990, II. 4/8.

A continuous building and shifting of coalitions weakens the decision-making process of UN agencies and causes negative consequences in regard to staff cohesion and internal functioning. UN agencies’ external boundaries remain weak, porous, and continuously open to manipulations by multiple interest groups and stakeholders, while internally, boundaries may be rigid, making it difficult to engage in constructive teamwork and inter-departmental collaboration.

The tendency towards external and internal coalition building is further heightened by the multi-national and multi-cultural composition of the UN staff, which presents a rich linguistic, national, religious, and cultural mixture. This built-in diversity and the resulting psychological and cultural differences can create ambiguities in staff loyalty and identification, which, in turn, further increase the likelihood of conflict and coalition building. Under ideal circumstances, those working for the bureaucracy should be politically neutral, recruited based on merit, and subject to “uniform standards regarding conditions of employment …, but in reality, the international civil servants are subject, like their national counterparts, to the political conditions of their environment.”19The Fluctuating Fortunes of the United Nations International Civil Service: Hostage to Politics or Undeservedly Criticised?, Robert Jordan, Public Administrative Review 51.4 (July/August 1991)

Yet, the conflict regarding loyalty is built into the system through two articles of the UN Charter, which unintentionally have led to tension and conflict. Article 100 reminds international servants neither to seek nor to receive instructions from any government or other authorities external to the UN organisation. It also reminds member states not to influence the staff and to respect the international character of their work and responsibility. Article 101 on the other hand, while not putting into question Article 100, asks for due geographical distribution of the UN staff. Both articles have been actively resisted at times by main member states for different reasons.20For instance, based on President Truman’s Executive Order 10,422 of 1952, US citizens used to be required to undergo full field security investigations before being “cleared” for work in UN organisations. This political control has since been abolished.

Leadership Challenge and Accountability

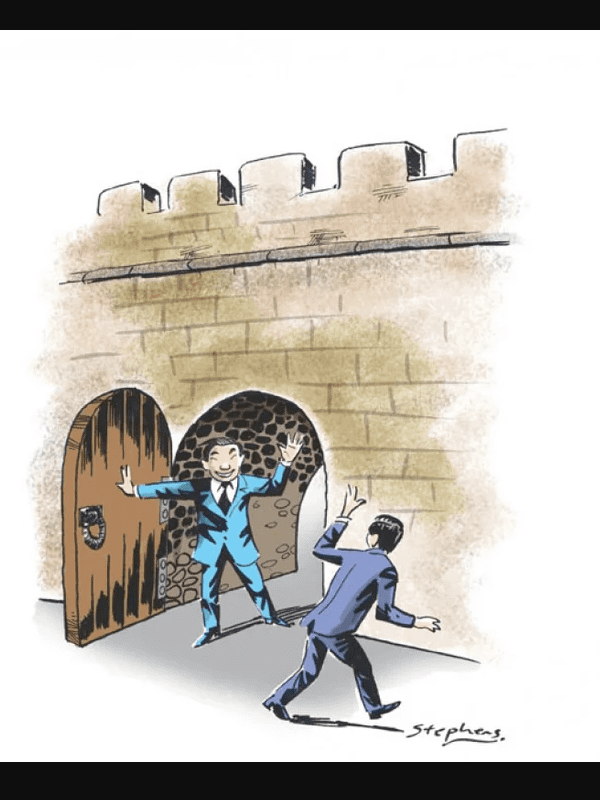

Continuous changes in its external environment combined with possible reactive or even proactive shiftiness of its internal environment have made UN agencies an especially difficult if not challenging place for leadership and management control. Figure 2 depicts a situation built on the previous “operational islands” concept but showing also the multitudes of influencing vectors reaching into a typical UN agency from outside at practically all levels of the hierarchy; at the same time, vectors are emanating from within the UN agency aiming at influencing stakeholders outside of the organisation.21Porous Boundaries and Power Politics: Contextual Constraints of Organisation Development Change Projects in the United Nations and Related Intergovernmental Organisations, Raymond Saner and Lichia Yiu, Gestalt Review 5.3 (2002).

through Porous Boundaries

Any attempt to reform current organisational practice in such a volatile environment has to face many forms of open and subtle resistance. Laurence Geri has reported successful organisational change at the World Health Organisation (WHO) but, overall, failure is common. Small successes give rise to a consultant’s celebration but the task of reform in UN agencies often appears to be of a Sisyphean nature.22New Public Management and the Reform of International Organizations, Laurence Geri, International Review of Administrative Sciences 67 (2001), 445-460.

What are “Porous Boundary” Phenomena?

When interacting with UN agencies, a foreign diplomat might feel confused about the seemingly fuzzy reality of organisational life in most of them. In contrast to the clear lines of command and clear boundaries concerning roles and responsibilities common in most private sector enterprises and public administrations, the organisational culture of UN agencies might best be described as resulting from “porous boundaries.”

Porous boundaries affect different aspects of organisational life. The concept helps to explain some of the performance issues confronting the UN system, although different agencies suffer from this phenomenon to varying degrees. Table 1 provides an overview of an organisational profile with porous boundaries.23 A description of porous boundaries first appeared in the work of Rainey, Sochor and Mintzberg. More recently, the authors of this paper expanded this concept to describe the unique organisational culture of the UN. For a more detailed overview of porous boundaries, see Saner and Yiu; “Porous Boundaries and Power Politics.”

Confronted with these specific characteristics, it is surprising that UN organisations have managed to deliver some outstanding achievements. For instance, the eradication of smallpox occurred through a successful global immunisation programme organised by the joint efforts of UNICEF24For more information on global immunisation programmes, see https://www.unicef.org/immunization/index.html. and the WHO. The protection and restoration of heritage sites around the world have been carried out by UNESCO. The ongoing efforts of various UN agencies have helped raise awareness of the situation of children and women in war-torn cities and other under-developed regions of the world. Through the continuous effort and championship of the UN, the plights of vulnerable groups around the world have been brought to the consciousness of a public that enjoys much higher standards of living. Concerted effort, under the umbrella of the UNDP, has brought infrastructure development in terms of water, transportation, health, education, and employment to different parts of the world, even if at times very slowly. Without a global infrastructure and the oversight of an international administration, these feats would not be easily accomplishable.

Conclusions

UN agencies are needed and so is the UN system. While this is obvious to most people, fewer people agree on what these agencies should do and how they should be organised and managed. The need for their continued efficient and effective existence is not in doubt, but, as Geri states: “International Organisations and their public stakeholders must protect their capacity to provide critical collective goods or their value to global society will be seriously compromised.”25New Public Management, Geri, 458.

This point is amply demonstrated with the current SARS crisis around the world. Without WHO’s Global Response and Alert Network, it would be difficult to imagine that a coordinated effort connecting different parts of the world could be mobilised to contain the further spread of the SARS virus. To entrust this task, for instance, to one national health centre such as the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, USA, would not be feasible politically nor effective from an operational perspective.

While very important – if not irreplaceable – for the international community, UN organisations also have to adapt and adjust to new environments and engage their member countries in constructive and efficient interactions. However, due to the multiple stakeholders involved, the organisational environment of UN agencies is and will be politicised for the foreseeable future. Hence, the porous boundary phenomena described above will continue for a long time.

As the mandates and tasks of the UN system increase almost day by day, the need for efficient management and an effective organisation is of paramount importance to all parties involved. Ways to improve existing and future UN agencies’ performance will be needed on a consistent and continuous basis. At the same time, foreign diplomats assigned to cover a UN agency should be mindful that undue external influence and political pressures may further aggravate the porous boundary phenomenon, endangering the long-term survival of the UN system. What is needed is a reduction of porous boundaries and a strengthening of the UN systems’ organisational structure and processes through more collaborative arrangements between member states and through the good offices of the diplomats who facilitate the dialogue between their capitals and the UN system.