Telephone diplomacy: Dialling the ‘red line’

Visit the other stops on our journey:

The telephone, radio, and telegraph constitute the three most important inventions that have shaped communication up until today. The telegraph delinked communication from physical transportation and travelling, the telephone transferred voice over distances, and the radio delinked communication from almost any physical medium.

These inventions have also strongly influenced diplomacy. The telephone enabled close contact between heads of state, including via various ‘red lines’. The radio had a strong impact on communications geopolitics. Some diplomatic issues – security, privacy, neutrality – that were raised in discussions surrounding the telephone and wireless communications are still being discussed today in the context of digital policy.

Invention of the telephone

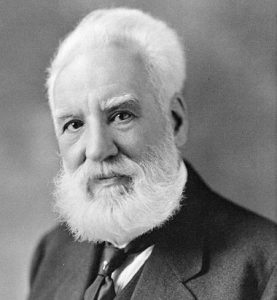

As with many innovations, the idea for the telephone came much earlier than the invention saw the light of day. The general and widely accepted view is that the inventor of the telephone was Alexander Graham Bell, but this invention was a culmination of the work of several individuals.

One of the early successful experiments with telephony was conducted by the Italian immigrant Antonio Meucci back in 1854. He invented the first voice-communicating device in 1854 and called it 'teletrofono'. Meucci experimented with telephony 20 years before Bell, but went bankrupt and couldn’t afford to patent it. He was recently officially acknowledged as the inventor of telephony by the US Congress.

In 1861, German Philippe Reis created a prototype of the telephone that transmitted voice sounds electrically over distance.

Elisha Gray invented the tone telegraph (harmonic telegraph) in 1875, and was granted the US patent 'Electric Telegraph for Transmitting Musical Tones'.

Although not the first to experiment with telephonic devices, what makes Bell important in the history of telephony is that he had enough capital and creativity to make telephony a practical utility. He, and the companies founded in his name, were the first to develop commercially practical telephones around which a successful business could be built. It can be argued that Bell invented the telephone industry.

Anti-telephone campaign

Bell encountered opposition from Western Union, a leading telegraph company at the time. He wanted to sell them his patents and technology for the telephone, but they thought it was laughable.

The idea is idiotic. Furthermore, why would any person want to use this ungainly and impractical device when he can send a messenger to the telegraph office [...] Technically, we do not see that this device will be ever capable of sending recognizable speech over a distance of several miles.

When Western Union could not stop the development of telephony, they signed a contract with Bell in 1879, stating that the telephone should only be used for personal conversations, while the telegraph would remain the main communications tool for businesses.

Obviously, such a clause could not be sustained, as the telephone became a frequently used communications tool by stockbrokers, bankers, lawyers, doctors, and other professionals who depended a great deal on communication.

Telecommunications network in 1900

The diffusion of this new technology was uneven, and was influenced by various technical, economic, and social factors. In 1900, an early communications divide, similar to the modern digital divide, was obvious.

A considerable difference between the USA and Europe was present, as was a north–south division within Europe itself, with the most dense telecommunications network in Sweden and the least dense in Italy.

Sometimes, such as in the case of France and Germany, which had similar levels of overall technological development, the same patterns did not apply to the adaptation of the telephone: Germany had a three times higher telephone penetration than France.

The importance of telephone in diplomacy

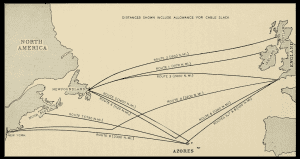

For a long time, the widespread use of the telephone was limited because it was difficult to sustain the strength of telephone signals over longer distances. It took a few decades to get the first direct telephone line between New York and San Francisco (1914) and even longer for transatlantic telephone lines between the USA and Europe (1956).

Transatlantic telephone cable routes, 1956. Source: Wikipedia.

The telephone had an enormous social impact. It became an integral part of the private, professional, and official lives in most societies. The real impact of the telephone on international relations was felt after the Second World War.

State leaders, especially those of the USA and USSR, started using the telephone in order to avoid further escalation in international crises. The telephone played an important role in several international crises, including:

- Six Day War in the Middle East in 1967

- India–Pakistan crisis in December 1971

- Arab–Israeli war of 1973

- Invasion of Afghanistan by the USSR in 1979

During the Cuban Crisis (1961), the USA and the Soviet Union were on the brink of war. The existing ways of communicating between Washington and Moscow were too slow for the events happening. It took Washington nearly 12 hours to receive and decode Nikita Khrushchev's 3,000 word initial message. By the time a reply had been written and edited by the White House, Moscow had sent another, tougher message. Under severe time pressure, both leaders ultimately decided to communicate through the media. After the crisis ended, the hotline proposal became an immediate priority. The first message, sent on 30 August, 1963, included numbers and an apostrophe to ensure the connection worked properly: 'The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog’s back 1234567890'. This is a common test message as it includes all 26 letters of the English alphabet. The first official use was to announce the assassination of John F. Kennedy to Russia.

It is said that the 1958 novel Red Alert by Peter George (which inspired Stanley Kubrick's movie Dr. Strangelove) gave government officials the idea to get in touch directly by showing the benefits of fast and direct conversations.

Although it was called the ‘red telephone’, it was actually first a telegraph, followed by a fax machine, and, lately, an advanced email system. The phrase ‘red telephone’ or ‘hotline’ is used to describe direct communication between the leaderships of two countries in a crisis.

It became a symbol of importance and exclusivity in relations between countries. It made other countries, mainly the UK and France, establish exclusive communication lines with Moscow. Today, leaders maintain exclusive contact via mobile phones.

Invention of radio communication

The rush for new inventions marked the whole of the 19th century. Towards the end of the century, wireless communications became the new scientific frontier. The very first use of radio-transmitted coded information was the result of the work of James Clerk Maxwell (Britain) and Heinrich Hertz (Germany), and their pioneering experiments with electromagnetic waves.

Maxwell provided the theoretical basis which Hertz confirmed through experiments. Their scientific discovery was used for subsequent inventions in the field of wireless communications, starting with wireless telegraphy, via wireless telephony, and concluding with radio broadcasting.

Among other inventors who worked on wireless communication were Eduard Branly, Oliver Lodge, and Alexander Popov. Additionally, Nikola Tesla was particularly noticeable for designing both emitters and receptors of electromagnetic waves. He used the term ‘wireless telegraphy’ (‘radio’ as a term appeared only after the First World War). Tesla had also designed a technical solution for transmitting power wirelessly.

The Indian professor Jagadis Chandra Bose from Calcutta was a pioneer in the research of radio technology, and demonstrated, for the first time ever, wireless communication using radio waves. He said, 'It is not the inventor but the invention that matters', and he never patented his work. Bose believed knowledge should be available to everyone and not constrained by patenting.

Capitalising on the previously described theoretical inventions, Italian scientist Guglielmo Marconi invented a wireless communication device.

In 1897, he registered a patent on his wireless telegraph. In addition to his invention, Marconi had other advantages and talents that helped him disseminate this device. He had family ties and business links with Great Britain, the world leader in telecommunications at the end of the 19th century. His marketing and public relations talents helped him to secure a few lucrative deals with the British Admiralty and British shipping companies.

In 1907, Marconi’s wireless telegraphy system became a public service for transatlantic exchanges between Europe and the USA. The main users of Marconi’s wireless telegraph were the British and Italian militaries.

Wireless geostrategy

The UK, together with the USA, held a monopoly in cable communications. At one point, they controlled over 70% of the global telegraph cable infrastructure.

The countries that were lagging behind, mainly Germany and France, used radio communication as a way to bypass this monopoly. This was particularly important for Germany whose weak cable-based communications infrastructure could not match it’s increasing geostrategic ambitions.

The German government supported research and development in the field of wireless communications. In 1903, two pioneering producers of wireless telegraphy sets, AEG and Siemens-Halske, merged under government pressure into a new company – Telefunken.

In an attempt to exploit his invention to the maximum, Marconi established a monopoly by not allowing operators who used his system to communicate with radios developed by other companies. Germany tried to challenge this monopoly at two International Radiotelegraph Conferences (1903 and 1906). Although the majority of countries were against Marconi’s monopoly, the objections of Great Britain and Italy kept the status quo until 1912 by not forcing Marconi to make his system interoperable with other producers.

Platform wars of the wireless telegraphy age

Things changed in 1912 after the British Titanic sank. One of the reasons why more passengers from the Titanic were not saved was that a nearby ship, the Californian, which was five miles away, did not receive the distress radio signal from the Titanic. The first ship that came to save the passengers was the Carpathia, which was 45 miles away.

"There were two major companies that provided the equipment and operators: The Marconi Company in New York City and Telefunken in Germany. The Titanic was subscribed to Marconi. The Marconi Company issued an edict that any operator who “talked” to a Telefunken ship would be immediately relieved of duty upon his return. Telefunken, in turn, issued the same order to their operators. This is why the Titanic SOS went unanswered by the Californian, a Telefunken ship, which we know now was only miles away. The Carpathia, a Marconi ship, heard the SOS and was able to respond, even though they were some distance away."

The Titanic disaster had a far-reaching impact on global telecommunications policy.

The International Radiotelegraph Conference held in 1912 ended Marconi’s monopoly by introducing the principle of interconnectivity among radiotelegraph systems.

The rising importance of media in diplomacy

The period between 1814 and 1914 was a golden period both for diplomacy and telecommunications. Congress of Vienna (1814) initiated the ‘Long Peace’, which introduced the Concert of Europe as the way to deal with international crises. The Concert of Europe was the vague consensus among European monarchies favouring preservation of territorial and political status quo. During this period, the important topics were privacy, security, and the neutrality of telecommunications.

The new political environment, influenced by the development of communications technology, had a considerable impact on questions of war and peace. Both diplomats and the military had to adjust their methods to the changing environment.

The emergence of the radio and the rising importance of the press led to a different operational environment for diplomats. The public began to challenge the closed and exclusive club of negotiators assembled through the Concert of Europe. Mass literacy and the growing number of newspapers, triggered the development of public opinion. Towards the end of the 19th century, diplomats became increasingly concerned about the reactions of their domestic publics which had become well informed about diplomatic activities. The development of public opinion also put pressure on governments and diplomatic services. Faced with this new threat, monarchies and governments introduced censorship and started using newspapers for foreign propaganda.

The US invasion of Cuba in 1898 was the first example of the importance of the media in international relations. Many historians believe that if it had not been for the media propaganda, this war could have been avoided. This is effectively illustrated in a story involving a journalist and the US media mogul Hearst The journalist sent the following message to Hearst: ‘Everything is quiet. There is no trouble here. There will be no war. Wish to return.’ The reply from Hearst was: ‘Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I’ll provide the war.’

Meanwhile in ... Africa

The development of the first telephone networks coincided with the great push of European powers to establish a more solid control over inland Africa and eventually divide the whole continent into their colonies. This effort was evident by the construction of railway lines that were closely followed by telegraph and telephone lines. Already by the 1890s, there were towns in Africa with telephone service.

However, the development of these telephone lines was primarily to serve the needs of their European masters and not the needs of the local population. The idea behind the establishment of telephone lines was to link African colonies with the capitals of the British, French, German, and other empires. Good connections were created between regions under the control of one empire, but not with the neighboring towns or regions ruled by a different European power.

This became painfully evident when, in the early 1960s, African nations got their independence. One famous example is that the telephone connection between Brazzaville and Kinshasa – standing on the opposite sides of the Congo River – needed to be rooted via Paris and Brussels. This was one of the problems posed in front of the Pan-African Telecommunications Network (PANAFTEL), formed in 1962 in Dakar, Senegal. However, it took more than a decade to implement the first steps of the project, and African nations started to get connected by a combination of copper wire and microwave links. The first submarine cables reached northern Africa in 1956, but it wasn’t until 1969 that they reached the sub-Saharan part of the continent.

The slow dissemination of land lines was one of the main reasons why mobile telephone technologies became the preferred option among users and thus developed at an astonishing speed.

Cheers! Absinth

Absinthe was the drink of the belle époque. This spirit, with a scandalous reputation, was adored by belle époque artists, condemned by anti-alcohol leagues, and long outlawed in Europe and the USA.

in the 1790s by Pierre Ordinaire, a French doctor living in Switzerland created the 'the green fairy', as they call absinthe. Ordinaire created absinthe with the intent for it to be used as an alcohol-based elixir distilled from the bitter-tasting herb Artemisia absinthium or wormwood. The wormwood plant holds a secret: it's naturally rich in thujone, a chemical compound believed to trigger inexplicable transformations of the mind. Many reported 'mind-illuminating' effects, believing that it enhanced perception, creativity, and enabled the ability to 'see beyond'.

Typically, there's a specific ritual when serving the drink. A special spoon holding a sugar cube sits on top of a glass with absinthe. The glass is then placed under a fountain, and water slowly drips over the sugar until it dissolves.

The popularity of absinthe skyrocketed in the 1850s when it was given to French troops for preventing malaria.

Various artists and writers, including Oscar Wilde, Vincent Van Gogh, Toulouse Lautrec, and Pablo Picasso, began to use absinthe to clear the mind and search for inspiration. In the novel For Whom the Bell Tolls, Hemingway's protagonist says absinthe is 'paque, bitter, tongue-numbing, brain-warming, stomach-warming, idea-changing liquid alchemy. It’s supposed to rot your brain out, but I don’t believe it. It only changes the ideas.'

The drink additionally provided inspiration for artists of symbolism, surrealism, modernism, impressionism, and cubism.

Its popularity was so great that by 1914 (when it was banned in France), sales in the country reached 36 million litres per year.

Listen to the podcast or watch the recording of our September Masterclass Telephone diplomacy: Dialling the 'red line'. Consult the PPT presentation.

Recordings from all sessions are available on our YouTube channel.

[Podcast]

[Recording]

For more information on this topic, you can consult the following resources:

The Culture of Time and Space 1880–1914.

Author: Kern S (1983) Harvard University Press

Stephen Kern writes about the sweeping changes in technology and culture between 1880 and World War I that created new modes of understanding and experiencing time and space.

Mapping World Communication (War, Progress, Culture)

Author: Mattelard A (1994) Translated by Susan Emanuel and James A. Cohen, The University of Minnesota Press

Armand Mattelart offers a history of modern communications that exposes the connection between militarism and the evolution of the media industry, while questioning the notion that technological innovation is always synonymous with progress. The history of modern media emerges in this account largely as a history of state control, wielded to discipline internal populations and combat external enemies.

Mattelart moves from the rise of the postal stamp to international telegraphy to the world press, and finds in each the hand of state strategy. In his analysis of the Gulf War, we see how the media can go beyond ideological service to become a tactical weapon. Beyond war and geopolitics, he examines the role of intensified economic competition in the forging of new international networks of information and communication, raising the fateful question of whether the emergence of these networks will lead to a uniform "world culture" or rather to greater fragmentation of the planet.

Dynamics of Modern Communication: The Shaping and Impact of New Telecommunication Technologies.

Author, Flichy P (1995) Sage Publications

Combining political economy with the sociology of innovation, Dynamics of Modern Communication is a comprehensive social history of communication technology from 1790 to the present. Author Patrice Flichy presents a careful critique and historical analysis of the social shaping and impact of the major communication technologies of the past 200 years. From the semaphore and telegraph to contemporary information technologies like the phonograph, photograph, telephone, radio, cinema, and television, this book focuses on the relationship between technological change and the social changes in which they were situated. Particular emphasis is put on four social processes: the birth of the modern state at the end of the 18th century, the development of stock markets, the transformation of private life in the modern nuclear family, and the individualism of the late 20th century.

The Practice of Diplomacy

Authors: Hamilton K and Langhorne R (1995) Routledge

Practice of Diplomacy has become established as a classic text in the study of diplomacy. The topics include: discussion of Ancient and non-European diplomacy including a more thorough treatment of pre-Hellenic and Muslim diplomacy and the diplomatic methods prevalent in the inter-state system of the Indian sub-continent; evaluation of human rights diplomacy from the nineteenth-century campaign against the slave trade onwards; a fully updated and revised account of the inter-war years and the diplomacy of the Cold War, drawing on the latest scholarship in the field; an entirely new chapter discussing core issues such as climate change; NGOs and coalitions of NGOs; trans-national corporations; foreign ministries and IGOs; the revolution in electronic communications; public diplomacy; transformational diplomacy and faith-based diplomacy.

The Rise of Modern Diplomacy 1450-1919

Author: M.S. Anderson, (1993), Longman

Though international relations and the rise and fall of European states are widely studied, little is available to students and non-specialists on the origins, development and operation of the diplomatic system through which these relations were conducted and regulated. Similarly neglected are the larger ideas and aspirations of international diplomacy that gradually emerged from its immediate functions.

This impressive survey, written by one of our most experienced international historians, and covering the 500 years in which European diplomacy was largely a world to itself, triumphantly fills that gap.

The Victorian Internet

Author: Tom Standage (1998), Phoenix

The Victorian Internet tells the colorful story of the telegraph's creation and remarkable impact, and of the visionaries, oddballs, and eccentrics who pioneered it, from the eighteenth-century French scientist Jean-Antoine Nollet to Samuel F. B. Morse and Thomas Edison. The electric telegraph nullified distance and shrank the world quicker and further than ever before or since, and its story mirrors and predicts that of the Internet in numerous ways.

The Invisible Weapon: Telecommunications and International Politics 1851-1945

Author: Headrick DR (1991) Oxford University Press

Telecommunication is, and always has been, a political technology, as the timely flow of information is a vital instrument of power. This book examines the political history of telecommunications between 1851, the year the first telegraph cable linked France and Britain, and the end of World War II. Headrick argues that telecommunication gives people options, not orders. During periods of peace, cables and radio were, as many had predicted, instruments of peace; in times of tension, they became instruments of politics, tools for rival interests, and weapons of war.

The book illuminates the political aspects of information technology: the speed of telegraphy, which could diffuse conflicts in far-flung empires, but which also hastened the deterioration of diplomacy on the brink of the First World War; the broad coverage of radio, which increased public knowledge and public pressure on governments, and consequently the political interest in controlling news; and the security of telecommunications, which made communications strategy, communications intelligence, and cryptography decisive tools during the two World Wars

Browse through the list of videos related to the invention of the telephone and wireless (radio) communication: