Renaissance diplomacy: Compromise as a solution to conflict

Visit the other stops on our journey:

The Renaissance (French: 'rebirth') was a period in European civilisation immediately following the Middle Ages. From the late 13th to the early 17th century, it brought a renewed interest in Classical learning, first to Italy, and later to all western and central Europe. The following developments during this period are important for understanding how Renaissance diplomacy emerged:

Culture: Great writers, such as Francesco Petrarca, Dante Alighieri, and Giovanni Boccaccio, emerged in this period, and art reached its peak with Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Sandro Botticelli.

Society: European society was deeply damaged by the Black Death (the bubonic plague pandemic) in the mid 14th century. Some countries lost up to 30–40% of their population which brought about extreme social changes.

Church: The great Western Schism (Great Schism) was a split within the Roman Catholic Church (1378–1417) during which there were two rival popes from Rome and Avignon, each with his own following and administrative offices. The followers of the two popes were divided chiefly along national lines, thus the dual papacy fostered the political antagonisms of the time. These rival claims to the papal throne damaged the prestige of the Catholic Church which began to lose its authority.

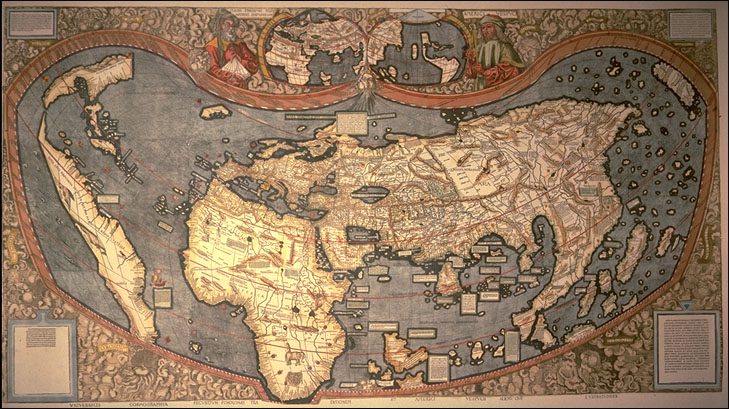

Discoveries: This period was marked by major discoveries. By 1488, the Portuguese had explored and mapped the African coastline down to the Cape of Good Hope. In 1492, Christopher Columbus persuaded the king and queen of Spain to experiment with the idea of sailing west into the Atlantic, when he incidentally discovered the New World (North and South America).

Waldseemüller map (1507) depicting the Americas. Source: J. Siebold.

Inventions: One of the most important (and by far the most influential) inventions of the 15th century was the printing press, invented by Johannes Gutenberg. It was modelled on the design of existing screw presses and could produce up to 3,600 pages per workday.

Politics: When the Renaissance began in the mid 14th century in Italy, Europe was divided into hundreds of independent states, each with its own laws and customs. Monarchs in France, England, and Spain responded to the chaotic situation by consolidating their power. A significant development in all three of these monarchies was the rise of nationalism, and pride in and loyalty to one's homeland. Monarchs centralised power and replaced the small networks of principalities and duchies.

Geostrategy: During the Renaissance, the Byzantine Empire collapsed with the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Spain emerged as a new power after completing the Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula in 1492, France united under Louis XI, Germany was divided into small principalities, Poland and Lithuania were important players in Eastern Europe, the Grand Duchy of Moscow started emerging, and in the south, the Ottoman Empire was well established in the Balkans.

Where did Renaissance diplomacy develop?

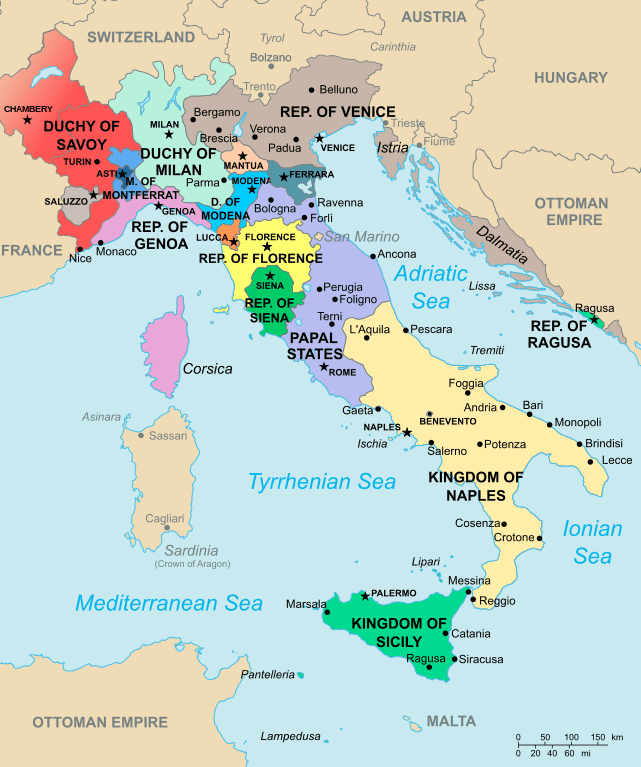

So far, we sketched a wider canvas in which Renaissance diplomacy appeared among Italian city-states in the 15th century, which is considered to be the beginning of modern diplomacy as we know it today, and included permanent diplomatic missions, and a rudimentary ministry of foreign affairs built around diplomatic archives.

Map of Italy in 1494. Source: Enok.

Renaissance diplomacy developed among numerous small and five major Italian city-states. The Papal States (territories under the direct sovereign rule of the pope), with Rome as its capital, was located in central Italy, while the southern part was occupied by the Kingdom of Naples. The north was dominated by city-states with strong manufacturing trading industries, including the Republic of Venice, the Duchy of Milan and the Republic of Florence.

During this period, the power of Catholic Church began to gradually decline; France, Spain, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire were not yet well established; and the Italian city-states found a way to develop their own way of handling internal relations.

The period of Italian Renaissance diplomacy lasted between 1350 and 1494 when Italy was invaded by France and gradually came under strong foreign influence, most notably the Habsburg.

The golden age of Italian Renaissance diplomacy lasted from 1454 to 1494. In 1454, the Peace of Lodi between Milan, Naples, and Florence was signed, which put an end to the wars between Milan and Venice. This period marked the first long peaceful period after a century of wars. Peace lasted until 1494 when Italy was invaded by France. The Peace of Lodi codified the diplomatic system among Italian city-states.

In the 16th century, his type of diplomatic practice spread throughout Europe, as far as England and Spain, initially through representatives of Italian city-states to these countries, and later through the exchange of ambassadors.

The emergence of Renaissance diplomacy

The emergence of Renaissance diplomacy is usually associated with two main characteristics of relations among Italian city-states:

- the lack of a hegemonic power

- a strong interest in cooperating and solving problems through peaceful means

'Allegory of Good Government' (detail) by Ambrogio Lorenzetti.

Italian city-states were too weak to impose themselves on their neighbours. Their armed forces consisted of mercenaries who were mainly interested in earning money and surviving. The city-states could not rely on military power. This ‘weakness’ created an ideal space for diplomacy. The only political tools were diplomatic ‘combinations’ (Italian: 'combinazioni') which survived until our time.

The main features of Renaissance diplomacy

It is widely accepted in diplomatic history that the first permanent diplomatic mission was established in 1450 (representing the Duke of Milan to Cosimo de’ Medici of Florence). The first envoy was Nicodemo di Pontremoli, known as ‘sweet Nicodemus’ in Genoa.

Italian Renaissance diplomacy was commercially driven, and Italian diplomats were often bankers and traders, but they also included well known names such as Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio in the 14th century, and Niccolò Machiavelli and Francesco Guicciardini in the early 16th century.

The main task of resident ambassadors was to gather information and develop relations. In a world without newspapers, they became crucial intelligence gatherers. They reported on the arrival of cargoes, the situation at court, the state of an alliance, military preparations, the atmosphere in the market, and political gossip.They needed to have good manners and oratory skills. At the end of the 15th century, Ludovico Sforza, the duke of Milan, stated that ‘the worth of a prince was seen in the men he sent to represent him abroad’.

'The Story of Esther' by Marco del Buono Giamberti.

Back in the capital, a new ministry of foreign affairs started emerging, first as an office that dealt with archives of diplomatic reports and, later on, it transformed into a more sophisticated system for collecting and analysing information, and coordinating diplomatic actions.

Diplomatic reporting was the key tool for communication between diplomatic missions and capital. Ambassadors were busy writing reports. Some of them dispatched one report each day. Many reports contained gossip about prominent personalities and life in the cities where the ambassadors served.

Venice was the most advanced state in developing reporting techniques. Besides daily reports, ambassadors had to prepare special reports called ‘relazioni’ which provided a strategic overview of the relationship between Venice and the country where the ambassador served. At the end of the mission, on return to Venice, each envoy was supposed to deliver a speech with detailed information about the situation in the state where the envoy was on mission, and after the session, the grand chancellor would include it in the secret archive of diplomatic documents. A Venetian official explained that the reason for archiving these documents was that this way ‘documents will be saved forever and reading of it could be useful to enlighten our present rulers and those who will come in the position in future’. In essence, renaissance reports were not that different from diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks a decade ago.

Developments in Renaissance diplomacy

Renaissance diplomats enjoyed diplomatic privileges and immunities. The person, premises, and communications of diplomats were protected by diplomatic immunities.

Renaissance diplomacy also inherited aspects of elaborate Byzantine ceremonies. Every detail of diplomatic protocol was negotiated as illustrated by Harold Nicholson: ‘At what exact stage in the proceedings should the ambassador remove or replace his hat?’

The Italians were well aware that it was important to influence the public. In this period, especially with the invention of the printing press, we have an early form of public diplomacy. Public diplomacy of this period also relied on personal communication and prominent personalities to shape the opinion of Italian city-states.

During this period of slow and undeveloped transportation and communications, diplomats were among the few with the privilege of travelling to remote places and bringing back information. In some cases, they were involved in early ‘science diplomacy’, by spreading knowledge and information, especially involving countries that were expanding their colonial exploration, such as Spain and Portugal.

For example, the French ambassador to Portugal, Jean Nicot, sent lemon and banana trees, as well as indigo imported from Asia back to Paris. Nicot was also first to bring tobacco to Paris, and it was after him that nicotine got its name.

Later on, in the 16th century, the concept of marriage diplomacy developed, not so much in Italy as in the rest of Europe. The complexity of marriage negotiations in 16th-century dynastic rule was at the heart of foreign affairs.

One of the famous marriages that affected European history of that time was the one between Henry VIII, king of England, and Queen Anne Boleyn that resulted in the creation of the Anglican Church, independent of the Vatican. Hans Holbein's painting The Ambassadors talks indirectly about this event.

'The Ambassadors' by Hans Holbein the Younger. Source: Google Art Project.

Painted in London in 1533, The Ambassadors, is a life-size double portrait that depicts Jean de Dinteville, once the French ambassador to the court of Henry VIII of England, with fellow diplomat Georges de Selve, bishop of Lavaur. King of France Francis I had sent two ambassadors to persuade the king of England not to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Henry VIII was dissatisfied that his marriage to Catherine had produced no surviving sons. They, like others, were unsuccessful, and history took its course, with divorce, marriage to Anne Boleyn, and the creation of the Anglican Church (as the English church renounced papal authority when Henry VIII failed to secure an annulment of his marriage to Catherine).

Apart from its historical context, The Ambassadors explains the spirit of the time and the role of diplomats. Between the two ambassadors is a display with two shelves of objects with strong symbolic meaning. The lower shelf has earthly symbols, including a globe, a merchant’s calculus book, a lute with a broken string, and a Lutheran hymn book. These items represent earthly interests, and the disorderly disputes that accompany them. The two ambassadors should overcome these earthly conflicts and elevate society to the upper shelf that symbolises a stable heavenly order, represented by tools of the science of astronomy, evoking the optimism of the Renaissance era.

Here, we have elements of both the Renaissance and science. The function of diplomats is to bridge these two ‘shelves’ – the earthly and the heavenly. Although they relied on science and the power of human creativity, the presence of a skull in the painting (a distorted skull, placed in the bottom center of the composition, visible only from a certain angle) is a reminder that pride in human knowledge and the power it gives, can be perilously vain.

Papal diplomacy

One of the main diplomatic developments in the Middle Ages was ‘papal diplomacy’. The Vatican’s main objective was to keep doctrinal control over Europe, and to suppress any actions aimed at challenging the role of the Roman Catholic Church. Papal diplomacy used a variety of diplomatic tools, such as negotiations, treaty-making, alliances, and arbitration, and developed considerable expertise in espionage, subversion, and conspiracy.

Portrait of Pope Alexander VI by Cristofano dell'Altissimo.

In addition to its theological and doctrinal interests, the Roman Catholic Church had complete control over the ‘information technology’ of the day, until the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press.

One of the main reasons was its choice of technology for the exchange of information. The decision by the Church to adopt parchment over papyrus favoured the spread of the papal-monastic network throughout Western Europe for three main reasons.

- Unlike papyrus, which was grown almost exclusively in the Nile delta region in Egypt, parchment was ideally suited to the decentralised agrarian-rural monastic network, because individual monasteries could remain self-sufficient, manufacturing parchment from the skins of their own livestock.

- The collapse of the Roman Empire and its trading system resulted in the near-total disappearance of papyrus from Western Europe. Parchment thus became the dominant medium of communication, and, however inadvertently, theRoman Catholic monastic order became the chief supplier of parchment.

- Most importantly, very few people were literate during the Middle Ages. The norm for Western Europeans, for whom much of life was violent and chaotic, was the spoken word, further reinforcing the Church's monopoly on the written word.

The relationship between parchment and the power of the Roman Catholic Church is a clear illustration where the mode of communication favoured the interests of the Church. Indeed, the clergy became the sole custodians and suppliers of written information, which had a significant impact on its share of power. The Church’s monopoly on language and the written word provided it with an advantage in the diplomatic scene of the Middle Ages. The missions of other players, such as the Frankish State, represented by Charlemagne, had to have at least one clergyman, because they were the only literate individuals of that age. This made it possible for the Church to be completely informed and to strongly influence the diplomatic developments of the Middle Ages.

Tools of Renaissance diplomacy

‘Combinazioni’ (diplomatic combinations) was the key modus operandi of Italian city-states. Urban centers emerged, populated by merchant and trade classes able to defend themselves. Money replaced land as the medium of exchange. Italian politics was a tangled net of alliances, conspiracies, and deceptions. The ‘combinazioni’ were a result of this environment.

As we mentioned, since the Italian city-states couldn’t promote their interest through military tools, they had to rely on diplomacy, and their key tool was ‘combinazioni’, i.e. different combinations and arrangements of players in city-states.

Other tools used included frequently changing alliances between city-states, bribery (borrowed from Byzantine diplomacy), and spying, all trademarks of Renaissance diplomacy. King of France Louis XI is said to have told his ambassadors: ‘Foreign envoys, they are lying to you! Lie to them more!’

On these moral deficiencies of Renaissance diplomacy, Harold Nicholson wrote: 'They bribed; they stimulated and financed rebellions; encouraged opposition parties; intervened in the most subversive ways in the internal affairs of the countries to which they were accredited; they lied, they spied, they stole.'

The spirit of that time is captured in the famous quote of diplomacy which you can find today in many tourist shops. Sir Henry Wotton, the envoy of the English king to Venice, said: ‘the ambassador is an honest man sent to lie abroad for the good of his country', whereby ‘lie’ meant both 'lying abroad' (residing abroad) and 'lying' (not telling the truth).

Portrait of Sir Henry Wotton. Source: Sotheby’s.

The problem was that Wotton's pun was lost in translation from English to Latin. The translation removed the ambiguity, using only the meaning ‘to deceive’. This famous quote almost ended Wotton’s career. His quote was used in Latin by the Catholic author Scioppius to show how devious protestant diplomats (Sir Wotton represented James I, an English king of the protestant religion) were. Sir Wotton managed to save his career and remained in the service of James I after this incident.

However, Sir Wotton’s quote explains a common (mis)perception of diplomacy which remains relevant in our own time. It also shows the power of double meanings in diplomacy. Solid diplomacy requires trust and correctness. If something is said, it should be the truth. Otherwise it should not be said.

Reformation and the invention of the printing press

The Renaissance is marked by important technical advancements. The most important one (as it underlies progress in so many other fields) was the invention of the printing press in 1450 by German publisher Johannes Gutenberg.

Johannes Gutenberg in his workshop. Source: Encyclopædia Britannica.

The invention spread like the fire, reaching Italy by 1467, Hungary and Poland in the 1470s, and Scandinavia by 1483. By 1500, around six million books were printed in Europe. Without the printing press, it is impossible to imagine that the Reformation would have occurred at all.

The invention of the printing press had a considerable impact on all functions of society, including diplomacy. The Church’s dominance through parchment-based writing was challenged. The Church’s participation in diplomacy gradually started to decrease. Clergymen no longer held a monopoly on literacy. No longer were they an indispensable part of every diplomatic mission.

As the American writer Mark Twain (1835−1910) once said:

What the world is today, good and bad, it owes to Gutenberg. Everything can be traced to this source, but we are bound to bring him homage, … for the bad that his colossal invention has brought about is overshadowed a thousand times by the good with which mankind has been favored.

Meanwhile in … The Americas

The Aztec Empire (also known as the Triple Alliance) was a shifting and fragile alliance of three principle city-states. The largest and most powerful among the three was Tenochtitlán. The empire exerted tremendous power over central Mexico for only 100 years (from the 1420s to 1521) before falling to Spanish conquistadors.

The Aztecs were famous for cruelties used to remain in power, but they also knew how to ‘negotiate’ with neighbouring cities.

Instead of bloody wars (resulting in a great number of captives who would be sacrificed to the gods), rivals were offered protection, stability, and economic integration into a flourishing trading system. If it subdued, the city-state would keep its ruling dynasty and order. In return, it had to pay an annual tribute, send its soldiers to fight along with the Aztecs, and acknowledge the supremacy of the Aztec gods. If a city or region failed to subdue after peaceful diplomatic persuasion led by Aztec ambassadors, the principal city would be sacked, and its king, nobility, and warriors were sacrificed to the Aztec gods. All kings and diplomats of subdued cities had to witness these gruesome acts.

The choice laid before the enemy was quite clear, and the Aztecs relied on their reputation for ruthlessness to raise the stakes of every potential war.

Their empire was in fact a very broad alliance, kept together by fear of bloody reprisals against mutineers. However, this turned out to be the key to their demise: except for trade, there was nothing but fear that held the whole structure together.

At its height, the Aztec Empire consisted of nearly 400 allied cities and 3 million people.

In the end, it wasn’t the war that wiped out the Aztecs, but the diseases that Europeans brought with them, i.e. smallpox and measles. The natives lacked immunity, and the population of Tenochtitlan fell by 40% in just one year. This made them an easy target for the European invaders.

Mexico City was built on the ruins of Tenochtitlán, and quickly became the most important European center in the New World (North and South America).

Cheers! Aqua vitae

The drink that gained popularity in the 15th century was called 'aqua vitae' (water of life), and was a strong spirit distilled from wine. It is first mentioned by the celebrated French alchemist and physician Arnaud de Villeneuve who named it 'aqua vitae', because of its rejuvenating effect on those who drank it, and as such, it was a very expensive drink.

Aqua vitae was also used as medicine, and was consumed both alone or mixed with other ingredients. But what was this drink exactly and why was it so special?

In the late Middle Ages, life expectancy was roughly 30 years, although, if a person survived to the age of 20, they could expect to make it to the ripe old age of 45.

Around 1350, the Black Death wiped out one-third of the population of Europe.

In a world so full of danger, many alchemists in Europe went looking for an elixir of life, a potion that could delay ageing, delay death, fight sickness, and even provide immortality. As an ingredient, strong alcohol seemed highly promising: if it could preserve herbs, fruit, flowers, and meat, it must be able to preserve the human body.

But it wasn't just its preservative qualities that made distilled alcohol special. Since it 'came from fire', many alchemists believed distillation actually put fire into the base liquid, making alcohol a combination of two elements: fire and water. It additionally appeared as a transparent vapour coiling through tubes like smoke, i.e. a 'spirit'.

Medicine of the time was dominated by the Ancient Greek idea of balancing 'humours' in the body: hot and cold, wet and dry. Aqua vitae was cold but produced a warming feeling; it was wet, but had a drying effect on the 'humours'; and, of course, it affected both mind and body extremely quickly.

Aqua vitae was not only a distilled spirit but also a complex mixture. One German recipe required 387 ingredients and 9 separate distillations spaced over a 2-year period to make 'white' aqua vitae. 28 more ingredients and 6 more months were needed to complete the 'yellow' aqua vitae.

While this and many other recipes were prized for their medicinal value, it didn't take people long to realise that aqua vitae got them drunk. After one Irish nobleman died from taking a bit more aqua vitae than he should have, it was said that ‘it was not aqua vitae to him, but aqua mortis [water of death]'. No one knows if this gentleman was drinking aqua vitae for health or for pleasure.

You can reference this text as

Jovan Kurbalija, Renaissance diplomacy: Compromise as a solution to conflict, 'Diplomacy and Technology: A historical journey', 2021, DiploFoundation

Listen to the podcast or watch the recording of our June Masterclass Renaissance diplomacy: Compromise as a solution to conflict. Consult the PPT presentation.

Recordings from all sessions are available on our YouTube channel.

[Podcast]

[Recording]

For more information on this topic, you can consult the following resources:

The Evolution of Diplomatic Method

Author: Harold Nicolson, Praeger, 1977

Four polished lectures by an eminent British historian dealing with diplomacy in Greece and Rome, Renaissance Italy, seventeenth century France, and the twentieth century.

Renaissance Diplomacy

Author: Garrett Mattingly, Cosimo Classics, 2009

This 1955 work is the classic history of the development of modern diplomacy in Renaissance Europe. Sometime after the year 1400, the diplomatic traditions of civilised cultures-which have existed as far back as the records of human history extend-took a sharp turn that was the result of new power relations in the newly modern world. Mattingly believed these could be illustrative of how nations and traditions change...and that we might apply those lessons to our own rapidly changing global culture. Discover: the legal framework of Medieval diplomacy; diplomatic practices in the 15th century; the Italian beginnings of modern diplomacy; precedents for resident embassies; the dynastic power relations of European nations in the 16th century; French diplomacy and the breaking-up of Christendom; the Habsburg system; early modern diplomacy, and more.

Diplomacy in Renaissance Rome, The Rise of the Resident Ambassador

Author: Catherine Fletcher, Cambridge University Press, 2015

Diplomacy in Renaissance Rome is an investigation of Renaissance diplomacy in practice. Presenting the first book-length study of this subject for sixty years, Catherine Fletcher substantially enhances our understanding of the envoy's role during this pivotal period for the development of diplomacy. Uniting rich but hitherto unexploited archival sources with recent insights from social and cultural history, Fletcher argues for the centrality of the papal court - and the city of Rome - in the formation of the modern European diplomatic system. The book addresses topics such as the political context from the return of the popes to Rome, the 1454 Peace of Lodi and after 1494 the Italian Wars; the assimilation of ambassadors into the ceremonial world; the prescriptive literature; trends in the personnel of diplomacy; an exploration of travel and communication practices; the city of Rome as a space for diplomacy; and the world of gift-giving.

Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century: Structure of Everyday Life, Vol. 1

Author: Fernand Braudel, University of California Press 1992

By examining in detail the material life of pre-industrial peoples around the world, Fernand Braudel significantly changed the way historians view their subject. Volume I describes food and drink, dress and housing, demography and family structure, energy and technology, money and credit, and the growth of towns.

The Rise of Modern Diplomacy, 1450-1919

Author: M.S. Anderson, Routledge, 1993

Though international relations and the rise and fall of European states are widely studied, little is available to students and non-specialists on the origins, development and operation of the diplomatic system through which these relations were conducted and regulated. Similarly neglected are the larger ideas and aspirations of international diplomacy that gradually emerged from its immediate functions.

This impressive survey, written by one of our most experienced international historians, and covering the 500 years in which European diplomacy was largely a world to itself, triumphantly fills that gap.

The Quest for Aqua Vitae

Author: Seth C. Rasmussen, Springer, 2014

Ethyl alcohol, or ethanol, is one of the most ubiquitous chemical compounds in the history of the chemical sciences. The generation of alcohol via fermentation is also one of the oldest forms of chemical technology, with the production of fermented beverages such as mead, beer, and wine predating the smelting of metals. By the 12th century, the ability to isolate alcohol from wine had moved this chemical species from a simple component of alcoholic beverages to both a new medicine and a powerful new solvent. Of course, this also began the long tradition of production of liqueurs and strong spirits for consumption. The use of alcohol as a fuel, however, did not occur until significantly later periods. This volume presents a general overview of the early history and chemistry of alcohol production and isolation, as well as a discussion of its early uses in both the chemical arts and medicine.

Time-travel to Renaissance Europe by listening to the music of the period! The Renaissance music was significantly influenced by the developments which define the early modern period: the rise of humanistic thought; the recovery of the literary and artistic heritage of ancient Greece and Rome; increased innovation and discovery; the growth of commercial enterprise; the rise of a bourgeois class; and the Protestant Reformation. From this changing society emerged a common, unifying musical language. The invention of the Gutenberg press made distribution of music and musical theory possible on a wide scale.

Here are some of the songs that may get us closer to the Renaissance: