Unravelling cyberattacks through a simulation game

A seemingly ordinary Monday. You enter your office, turn on your computer, and grab a cup of coffee. As you settle in your desk to check your emails and connect to the internal communications system, you start realising it’s taking way too long to connect… Refreshing or disconnecting and trying to reconnect doesn’t seem to help either. You’re starting to get anxious, grumbling as you look at your busy calendar for the day, thinking about what could be wrong…

You decide to call IT; ‘There seems to be a DDoS attack,’ they say, quickly adding: ‘That is a network flood which caused our communication services to shut down’. Later, you find out that someone in the office interacted with a phishing email and clicked on a link within, which turned out to be infected, letting ransomware into the IT networks of your institution. Panicking yet?

What if we said that in this story, you are a diplomat working with the UN First Committee and this attack is targeting – the UN? And surely, you don’t know what the real target is yet: Is it the UN-managed IT services, or an institution connected to it? Who’s behind the cyberattack? What do they want? Is the DDoS attack just the beginning – or is it a smoke screen for other ongoing operations?

Diplomats, as well as countless professionals from various backgrounds who deal with digital policy matters, usually do not come from technical backgrounds. Yet, the decisions they make about challenges in cyberspace may significantly impact international security and peace.

Cybersecurity is climbing up on the political agendas, and diplomats and professionals need to understand the technological aspects behind it.

So – how can diplomats and professionals best understand the technicalities of how and why cyberattacks happen, without surviving such an attack?

Learning the complexities of technical attribution

Today, news headlines are full of serious cyberattacks. These are often followed by countries blaming each other for conducting or supporting a cyberattack. How can we make sure that accusations are substantiated by evidence – what we call ‘attribution’? Attributing a cyberattack to an organised hacker group – especially to a state – remains a complex and multilayered undertaking. According to the report adopted by the UN Group of Governmental Experts, or UN GGE, in May 2021 ‘a broad range of factors should be considered before establishing the source of an ICT incident’ (voluntary norm 13b, par. 22-28).

Attribution involves political, legal, and technical layers. Political attribution should, ideally, take into account evidence, intelligence , and the broader geopolitical context . Legal attribution should ensure collecting, preserving, and presenting evidence according to the requirements of a certain jurisdiction. Technical attribution , in most cases, should be the crucial foundation for the other two types of attribution.

The primary aim of technical attribution is to collect all the necessary evidence and technical information to respond to as many questions as possible. What or who is an intended target? Which techniques were applied? How severe was the incident, and what were the consequences? Understanding cybersecurity events by conducting technical analysis and evaluation, is a prerequisite for responding effectively to them. This, in turn, contributes to maintaining stability in cyberspace through international cooperation.

Political and legal attribution is in general a prerogative of states. However, it is the private sector, technical community, and civil society who can meaningfully support states with technical attribution. Non-state actors can support governments by analysing cyber incidents from a technical standpoint to aggregate attacks into groups and tie them to possible threat actors.

In addition, they can provide valuable learning and capacity building opportunities for diplomats. This brings us to the response to the question posed earlier: One powerful way for diplomats to understand cyberattacks and learn the complexities of technical attribution is – through simulation games!

Wait! You said ‘games’?

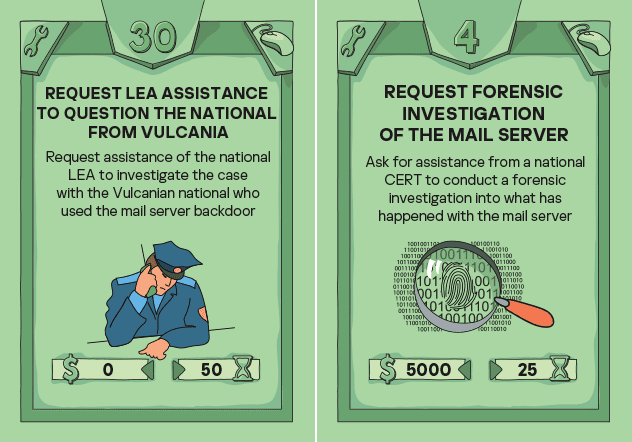

Exactly. Kaspersky’s international team, with the support of Diplo, have created a gamified virtual cybersecurity exercise for diplomats and professionals! It’s a security training based on the Kaspersky Interactive Protection Simulation (KIPS) with its special edition on technical attribution, in addition to its previous cybersecurity editions that teach cybersecurity through protecting airports, banks, water stations, and more. This special edition focuses on technical attribution in cyberattacks. KIPS places players in a simulated environment where they become diplomats in a fictional world, facing cyberattack(s) against the UN First Committee which deals with disarmament, global challenges, and threats (including in cyberspace), and maintaining world peace and international security. KIPS is a ‘detective learning exercise’ where players are provided with five threat actor profiles – only one of them is the culprit conducting a sophisticated cyberattack against UN infrastructure. Action cards are played, and thus decisions made by players through five turns, will either lead them to the most accurate technical analysis and help understand who is the culprit by collecting technical pieces of evidence, or will spark greater political tension and cyber instability if the riddle is not solved. The game allows up to 300 virtual players, and it can be played individually or in groups, both online or in person.

This technical attribution version aims to teach players about the complexities of technical attribution, and help them better understand what’s really happening in a cyberattack.

KIPS simulation game on technical attribution requires players to choose among many action cards to play in each turn – taking into consideration the available time and money.

Experiences of the first rounds of the game, by actual diplomats, legal and policy experts from international and regional organisations, and cyber diplomacy professionals from companies and organisations confirm that gamification is of great value to better understand what is ‘under the bonnet’ of cyberattacks . Moreover, the debriefs organised after each session allow for open reflection and discussion among players and cyber diplomacy experts on various issues such as the links between technical and political attribution, challenges of the applicability of international law to cyberspace, and modalities of public-private partnership in addressing high-impact cyber incidents.

KIPS games can be played either face-to-face or online, individually or in groups.

Here’s what some of our very first players thought of the game:

‘The likelihood of an incident like the one simulated is high and diplomats need to familiarise themselves with the different levels of attribution and be in a position to support technical authorities and actually be interested in pursuing technical certainty and understand its relevance.’

Moliehi Makumane, Researcher, UNIDIR

‘The Simulation is quite fascinating and entertaining. With KIPS, policymakers will be confronted with a variety of cyber attack scenarios and situations that will require proper response and engagement with the technical community.’

Harditya Suryawanto, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia

‘Playing games as a cyber diplomat is highly unusual. However the Cyber Stability Games takes a refreshing view towards exercising the complexities of managing an international cyber incident. It showcases well the lack of information, the time pressure and the limits on resources, while also adding a bit of competition. I can highly recommend to everyone interested in cyber policy to play this game.’

Szilvia Tóth, Cyber Security Officer, Secretariat/Transnational Threats Department, OSCE

How can I play and learn more?

We would be glad to organise a security training session for your organisation! To learn more or to play, consult the game whitepaper , and contact Kaspersky .

Click to show page navigation!