What’s new with cybersecurity negotiations? The informal OEWG consultations on CBMs

Author: Diplo Team

The UN Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security held informal intersessional consultations on confidence-building measures (CBMs) between 5-9 December in New York. Following the chair’s guiding questions, delegations focused on establishing a directory of national Points of Contact (PoC), and which types of PoC should be listed in the directory. There were a number of other proposals related to CBMs and capacity building. The UN allocating more resources for capacity building programmes, a cyber fellowship programme being established under the OEWG, and a global cybersecurity cooperation portal being created were among the proposals that stood out.

The global PoC directory

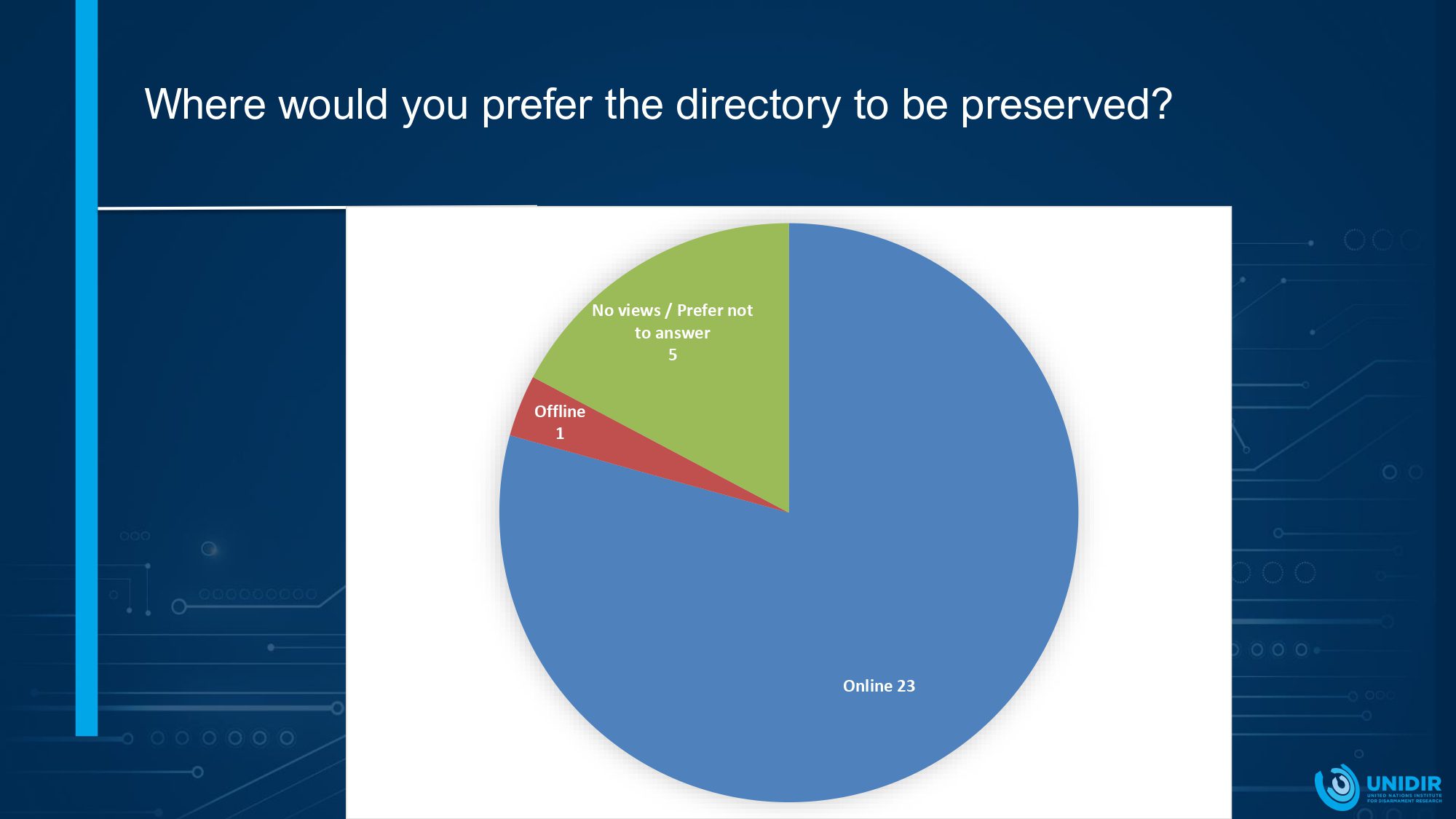

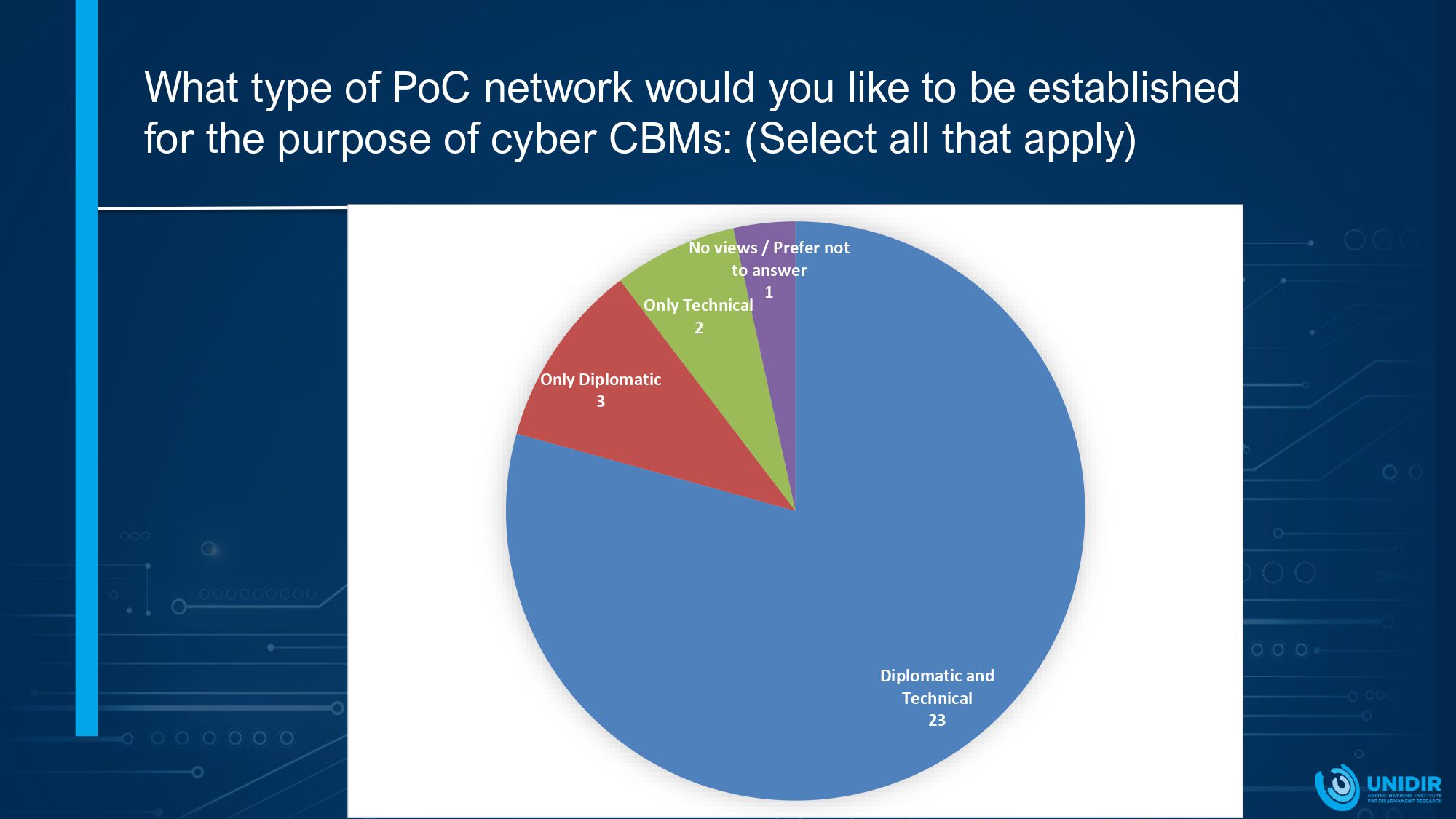

As the PoC directory was discussed by the OEWG, the disarmament arms of UN, UNODA and UNIDIR presented an overview of current positions. The two presentations indicated general agreement about the importance of creating a PoC directory (figure 1), suggested the role of UNODA Secretariat in its maintenance and emphasised the online format available in all UN official languages (figure 2).

Figure 1: The majority of states agreed that the establishment of a PoC directory is important. Source: UNIDIR.

Figure 2: The majority of states expressed a preference for an online PoC directory. Source: UNIDIR.

Building on this summary, delegations shared the view that CBMs should be implemented gradually and that the PoC directory constitutes a good starting point. A vast majority of states emphasised the need to build on existing PoC infrastructures from regional organisations and integrate them so efforts and information aren’t duplicated.

What kind of activities could be pursued by the PoCs, and how the directory could be used were questions that remained open. Italy and Germany, for instance, supported the low-hanging fruit perspective, explaining that the higher the level of details the PoC directory ambitions to collect, the more difficult it will be to agree on its format. France suggested that the PoC should start with very simple tasks, while South Korea suggested that the PoC should stay flexible when it comes to details, modalities, and timelines. Tanzania suggested that PoC could assess the capacity-building needs and requirements of each region or each nation. Iran stated that capacity building was a prerequisite for developing countries to implement such a CBM. The UK, however, expressed concerns that the PoC directory could become a channel for capacity-building requests, such as visits and best practice exchange in CERTs.

The type of PoC that should be added to the directory was also a point of contention. According to the UNODA and UNIDIR summary of previous positions, the majority of states were in favour of having two POCs – a diplomatic and a technical one with distinct functions. Yet, some states were reluctant to have PoCs at different levels (figure 3).

Figure 3: The majority of states expressed a preference for diplomatic and technical PoC directories. Source: UNIDIR.

Many states were in favour of appointing both a diplomatic (or policy) PoC and a technical PoC. However, some argued for starting with either a diplomatic or technical PoC depending on the state’s capacity to nominate one. Others, like Estonia, proposed to have a single PoC for efficiency. Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Fiji, Germany, Israel, the Republic of Korea, the Netherlands, Singapore, and Uruguay gathered around the informal working group on implementing CBMs globally), and presented an outline of recommended PoC tasks and timeline of next steps. They also proposed an agreement on modalities of the UN PoC directory to be included in the July 2023 Annual Progress Report and endorsed with a resolution by the First Committee subsequently.

Open stakeholder consultations on CBMs

The open stakeholder consultations on CBMs provided time for inputs from all interested stakeholders. For the first time in the OEWG process, there were official interventions from regional and sub-regional organisations sharing their experience with CBMs, cooperation between their member states, current PoC structures, and best practices related to CBMs. All speakers supported the UN role in creating a global PoC structure and underscored the importance of building upon the existing PoC networks and CBMs. The majority of speakers called for the inclusion of non-state stakeholders in the process of establishing PoC directories and CBMs.

India proposed creating an online and centralised ‘Global Cybersecurity Cooperation Portal’ (GCSCP) for global cooperation in ICT security. It would aim to reduce multiple sites with the same purpose. The portal would be set under UN auspices, and the cost should be borne by the UN Secretariat. India also suggested that the GCSCP should be modular and incrementally built to respond to evolving needs, and allow ideas to mature. With both public and private interfaces, the portal would allow delegations to modulate which information is public. The GCSCP would contain:

(a) A repository of important documents generated during intergovernmental discussions on ICT security, of particular relevance for small delegations who will engage in the OEWG in the upcoming years

(b) Mapping of available assistance providers and resources, that allow countries (c) PoC directory

(d) Conferences and events calendar

(e) Incident reporting tool

The proposal was well-received by delegations who expressed interest in discussing the project further. Egypt expressed concerns about the security of such a platform, the Philippines asked the secretariat to report on the feasibility and cost of the portal, while the Netherlands proposed to merge platforms that have already been established.

Other substantive issues

States also discussed existing and potential threats, rules, norms and principles, international law, capacity building, and regular institutional dialogue.

Existing and potential threats

Existing and potential threats

Many states – including Switzerland, El Salvador, Netherlands, Israel and Ireland – expressed dissatisfaction with the fact that ransomware was not included in the annual progress report.

There were recurring issues. Activities that undermine trust and confidence in political and electoral processes and public institutions were underlined by the Netherlands. Iran highlighted: (a) use of the ICTs to destabilise and interfere in the internal systems and processes of a state and create conflict among nations, races and ethnic minorities, (b) unilateral coercive measures against a state in the ICT domain, (c) disinformation campaigns, fabricated image building and xenophobia against states through the use of ICT, (d) lack of responsibility of the private sector and platforms with extraterritorial impact in ICT domain. Russia similarly noted unlawful restrictive measures against particular states and the need to counter deploying in the national information space of states free access tools for conducting cyberattacks.

Israel underlined the risks of hacking-as-a-service, provided by cybercriminals and cyberterrorists as proxies of states. Information sharing among defenders should be enhanced, and common cybersecurity standards for different industries should be developed, in particular for the civil aviation and maritime industries which are at great risk. Application of new technologies was also noted as a concern, with the Netherlands putting forward the application of new technologies in cyber operations and Ireland highlighting the use of quantum computing to crack encryption.

Norms, rules and principles

The main point of contention in discussions on rules, norms and principles remained whether new norms are needed, with standpoints ranging from (a) developing new norms is needed, (b) to focusing on implementation of existing 11 voluntary norms before/while developing new ones,(c) to developing new norms is not needed.

International law

International law

While reaffirming that the existing international law applies to cyberspace, states discussed gaps in its applicability. France argued that the priority was to exchange views to build common understandings of how precisely international law applies, which may lead to identifying gaps and the need to develop binding norms if appropriate. As a particular gap, Austria identified the relationship between what has been defined as non-binding norms (like due diligence) and the well-established customary law.

Expectedly, Russia, Iran, Cuba, and Pakistan underlined that there are gaps caused by unique attributes and the transnational nature of ICTs which could only be filled by the development of legally binding instruments. Russia proposed that the OEWG discussions should focus on two dimensions: (a) how specific principles apply to the use of ICTs, and (b) which aspects of interstate relations remain unregulated by international law. In this view, Russia notably proposed that the OEWG could elaborate specific international legal mechanisms to decrease public unsubstantiated attribution of cyberattacks. In an unrelated contribution on norms, Switzerland proposed providing explanatory guidance on attribution, as more states publicly attribute cyber incidents in recent times.

Another major thorny issue originated from a joint concept paper presented by Canada and Switzerland which proposed to prioritise the discussions on certain topics – namely the Charter of the UN, peaceful settlement of disputes, International Humanitarian Law, and state responsibility. The logic behind the suggestion was that details on how international law applies are needed in order to build tailored CBMs for different states’ needs. Focusing on specific topics would notably be easier for delegations from smaller states as well as an opportunity for capacity building, New Zealand noted. While a vast majority of states welcomed and supported this proposal, Russia, Iran, and Cuba were against it. Cuba expressed concerns that if some items are prioritised, others will be left behind, and Iran argued that such an approach could damage consensus.

No progress was made in discussions on the applicability of International Humanitarian Law (IHL).

Capacity building

Capacity building

Something we’ve heard over and over again is that capacity building must be needs-driven and adjusted to local contexts. Regional approaches can ensure that the needs of the states will be taken into account, as Chile and the Global Forum on Cyber Expertise (GFCE) highlighted. Canada stated that the GFCE should continue its coordination role in cyber capacity building, and that the OEWG could leverage GFCE in this role.

The UK proposed better contact with digital development programmes to ensure alignment with capacity-building principles. France, Colombia, and the Philippines noted that the OEWG could support the mapping of capacity building needs using existing instruments and frameworks. France also highlighted that the Programme of Action (PoA) could strengthen capacity building initiatives.

Raising the cyber capacities of developing countries was also discussed. Some countries, such as Egypt, Iran and Indonesia stated the UN should facilitate resource allocation for capacity building programmes. Iran stated that a dedicated trust fund should be established to finance cybersecurity training and education, transfer of technology, technical assistance, and financial support. This proposal was supported by Pakistan and Nicaragua. Iran proposed that the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) be considered for capacity building.

To provide developing states with capacities that allow meaningful participation in cyber processes, creating a cyber fellowship programme under the UN and OEWG was proposed by Egypt. Supported by Pakistan and Indonesia, the proposed programme would be akin to the one presented by the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in the Programme of Action (PoA) on small arms and light weapons.

Regular institutional dialogue

The PoA, a joint proposal by Egypt and France, set the pace for the thematic session on regular institutional dialogue. First proposed in 2020, the PoA is an action-oriented mechanism envisioned to provide concrete support for the implementation of agreed norms. The resolution of the UN First Committee, adopted shortly before this OEWG meeting, sets the PoA as a permanent mechanism to start once the current OEWG is completed.

Many states welcomed the proposal, with a number of countries supporting meetings within OEWG in 2023 to discuss modalities of PoA, including Egypt, France, South Africa, Japan, EU, Netherlands, US, Columbia, Germany, and Pakistan.

Some states expressed their opposition to the PoA. Nicaragua, Syria, and Iran stressed that the OEWG should remain the only negotiating mechanism. Russia, Nicaragua, Israel, Iran, and China advanced the view that the PoA or any new mechanism should be adopted on a consensus basis within the OEWG rather than imposed by a group of states. Russia also qualified the conceptual basis of the PoA as ‘irrational’, as it is a mechanism which will be established in 2025 to implement voluntary norms agreed upon in 2015.

However, Nicaragua, Syria and Iran noted that the PoA could be discussed at the OEWG, even as they do not put much faith in its success. Russia stated that the OEWG has three years until 2025 – more than enough time to jointly develop an understanding on the utility of creating a PoA.

Other proposals regarding the modalities of the institutional dialogue emerged during the discussion. Russia thought of a mechanism that would allow formalising decisions as soon as they are agreed upon by the group. In the same vein, Iran argued that it was essential to resume the practice of paragraph-by-paragraph negotiation. Russia also proposed that the OEWG should consider streamlining stakeholders’ interventions in separate sessions or intersessional meetings, bearing in mind their consultative status. The UK answered that comments from stakeholders were already overly streamlined. The UK and France also raised the idea of building a checklist of the key components that any future mechanism should include, as was done by UNIDIR for the PoC directory.

Next steps

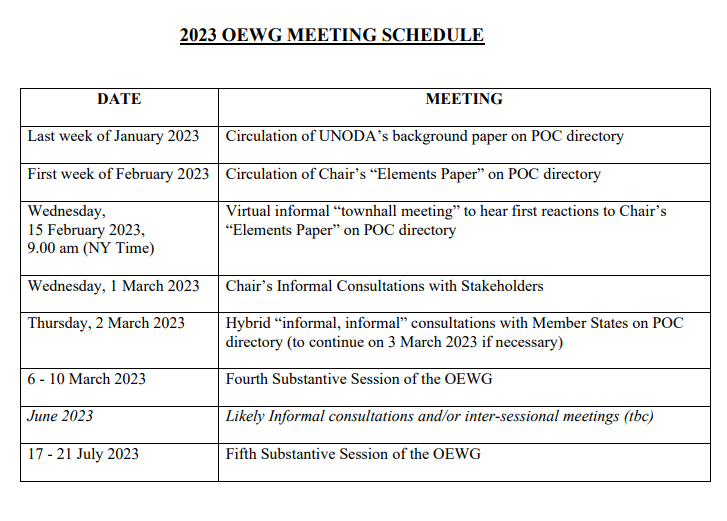

The chair noted that the PoC directory has a good potential to be considered in July 2023 with the second annual progress report. The chair will prepare a paper with elements of PoC for further discussion among member states by early February 2023, followed by an informal virtual meeting to get initial reactions to that.

The chair has since published a more detailed schedule of meetings, listed below.

By Andrijana Gavrilović, Pavlina Ittelson, Salomé Petit, Vladimir Radunović, Jeanne-louise Roellinger, and Ilona Stadnik

Click to show page navigation!

Existing and potential threats

Existing and potential threats International law

International law Capacity building

Capacity building