The UN process to negotiate the cybercrime convention: Key takeaways from the fifth session

Updated on 03 April 2024

The almost two-week-long fifth session of the UN’s Ad Hoc Committee (AHC) to Elaborate a Comprehensive International Convention on Countering the Use of Information and Communications Technologies for Criminal Purpose came to a close. The UN member states continued to discuss the consolidated negotiating document (CND) (21 April 2023), particularly focusing on the preamble, the provisions on international cooperation, preventive measures, technical assistance, and mechanisms for the implementation of the future convention.

Below, we share the key takeaways from the text-based negotiations that took place during the fifth substantive session.

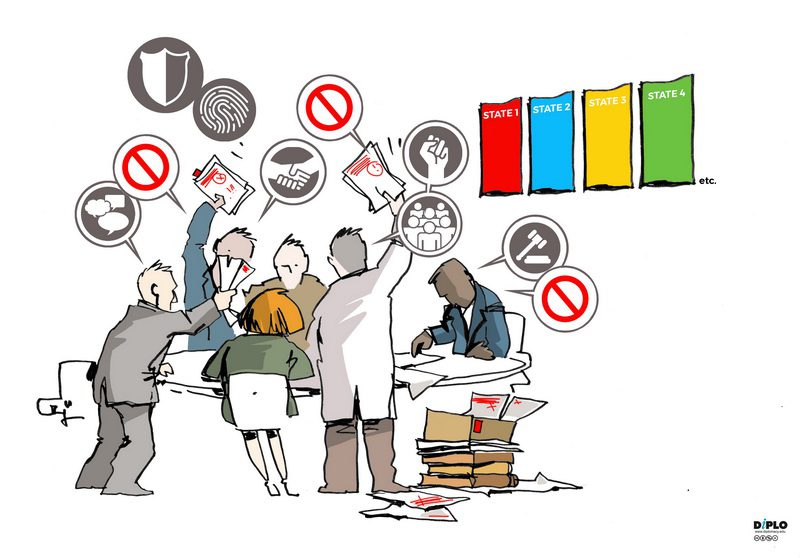

Disagreements on the scope of international cooperation and, in particular, the sharing of electronic evidence

From the start of the session, it became evident that at least two main opinions exist among the states in regard to the scope of international cooperation and the sharing of electronic evidence. Some delegations stated they would like to keep a broader scope across a more comprehensive range of offences, including those not covered by the convention. Others stated that they prefer to follow a limited scope and limit the sharing of electronic evidence only to crimes defined in the convention. In addition, some delegations (e.g. African group) have not yet expressed a clear position, and stated that they are open to considering a broader scope.

At the same time, the majority of states shared the common view that baseline restrictions should apply to international cooperation: the dual criminality principle and a threshold of serious crimes. In regard to the threshold of serious crimes, most states preferred to follow the definition provided in the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime (UNTOC), where such crimes are defined as offences punishable by a term of imprisonment of at least four years or more.

States have also expressed different views on whether international cooperation should strictly apply to criminal matters. In particular, some delegations supported a limited scope to criminal matters and not to civil and administrative matters (e.g. Argentina, EU, Malaysia). In contrast, others supported an extended scope of international cooperation, but that is subject to domestic legal systems (e.g. Brazil, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Guatemala).

Data protection safeguards for international cooperation cause another disagreement, even between like-minded countries

While discussing the chapter on international cooperation, delegations have shared different views on whether data protection and human rights safeguards should be kept in the provisions on international cooperation. If yes, how can they be strengthened?

A number of delegations, in particular the EU and its member states, support the retention of human rights safeguards in this chapter. They have also proposed much stronger principles to ensure data protection during the exchange of electronic evidence. The EU outlined several principles for the production of personal data to be included in the convention, in line with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The EU and its member states objected to provisions on the real-time collection of traffic data and the interception of content data. Their concerns stem from the perceived intrusiveness of these measures and the potential impact on citizens’ rights.

A second group of delegations has been generally inclined to enhance safeguards, and expressed their interest in proposals from the EU. They have not yet provided specifics on their national positions, but rather expressed an openness to continue the discussion.

A third group of states has called for the deletion of the human-rights-related paras and argued that they are unnecessary and duplicate earlier provisions (discussed at previous AHC sessions).

Finally, several other states have, in general, agreed that data protection safeguards are important for international cooperation, but disagreed with the EU’s proposal to negotiate a ‘full-blown data protection convention’ within the cybercrime convention. In particular, the US delegation proposed an alternative solution: the requested states should respond to personal data requests by applying their own national legislation. States could also deny requests if the requesting state has mistreated data received from the transmitting state in the past.

Grounds for rejection of extradition requests and politically motivated offences

Several delegations (e.g. EU and its member states, USA, Japan, Australia) have voiced their support for retaining the option to reject extradition requests based on the political nature of the offence and, at the same time, did not support proposals from delegations (e.g. Russia) to insert the wording:

‘A request for extradition or legal assistance in criminal matters, including the search, seizure, confiscation and recovery of property obtained by criminal means, related to such offence shall not be rejected solely on the groups that it related to a political offence, an offence associated with a political offence or a politically motivated offence.’

Some other states (e.g. China) also argued that none of the offences listed in the convention should be considered political offences. Certain delegations (e.g. Canada) have made it clear that without such provisions, they cannot accept the convention in its entirety.

At the same time, some delegations (e.g. Russia, Syria, Nicaragua) also called for adding a new paragraph to Article 58, allowing the requested state party to reject an extradition request if it would harm the sovereignty, security, public order, or other essential interests of a state party. A number of delegations (e.g. New Zealand, USA) did not support it.

Clarifying the term ‘developing states’ and the role of stakeholders in technical assistance chapters

To ensure effective technical assistance among states, many delegations (e.g. Cabo Verde, Japan) proposed further clarifications in defining the term ‘developing countries’ in the convention to clearly reflect different types of ‘developing countries’ and, therefore, different types of technical assistance.

The UK proposed changing the term ‘developing states’ to ‘countries in special situations, in particular African countries, least developed countries, landlocked developing countries and small island developing states’.Several delegations (e.g. Australia, Paraguay) supported this approach.

The role of stakeholders in the context of technical assistance chapters was another topic in the negotiations. The Netherlands and others emphasised the essential role of academia, civil society, the technical community, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in enhancing the capacity and expertise to combat cybercrime. The Republic of Korea stressed that stronger cooperation among stakeholders is necessary to bridge the digital gap between countries and raise awareness about cybercrime.

In regard to Article 86, Nigeria raised the question of whether stakeholders will be seen as providers or beneficiaries of technical assistance, and if considered the latter, then such provision should be deleted. Other delegations argued that it is imperative to ensure that stakeholders are not put at the same level of legal obligations as states.

Different views between delegations on technical assistance measures

The delegations discussed a wide list of technical assistance measures: from creating special programmes and training on methods and techniques used in the prevention, investigation, and prosecution of the offences, the development of strategic policies and legislation, to more specific and targeted proposals such as building capacities in the collection of electronic evidence and forensic analysis, tracing communication and virtual assets for criminal investigations, the detection and monitoring of movements, etc.

Some countries argued that the CND includes a too prescriptive and long list of technical-assistance-related proposals which may prevent a ‘technology neutral’ convention, while other delegations did not support this and called for the inclusion of specific provisions, such as the transfer of technology and information. This, in particular, divided states into two groups.

The first group believes that technology transfer is imperative for reinforcing the capabilities of law enforcement agencies to prevent future cybercrime. Such technology transfer might include specialised equipment such as surveillance means and other material support, especially for developing countries. The second group of delegations (e.g. USA, EU and its member states, New Zealand) opposed the inclusion of technology transfer. The UK added that such a proposal does not fall within the scope of the capacity development and technical assistance approach.

Different views have been highlighted in several other subtopics: information exchange through a competent body, and human-rights- and gender-related aspects in technical assistance. Cameroon, in particular, proposed amendments for information exchange to a competent body to ‘ensure effective sharing of information related to cyber threats, corrective measures and good practices in preventing, detecting and countering emerging cyber threat’. This was opposed by the US delegation.

In regard to human rights and gender-sensitive approaches, the delegations disagreed over the extent to which states should be guided by these aspects for technical assistance in the context of future conventions. Some delegations pushed back and did not support reiterating provisions on human rights and gender in different chapters, arguing that their inclusion in the preamble would be sufficient. Other states had a different view and pushed for adding more specific language in the CND.

Related concerns have been raised about some forms of technical assistance. In particular, some states (e.g. the EU and its member states, Australia, Canada) proposed to exclude amendments from Article 86 and Article 87 (2) (g), which encourage the ‘modern law enforcement equipment and technique and the use thereof including electronic surveillance’ (though the latter has not been defined in the convention either). The delegations that reject these amendments argue that such forms of technical assistance are not in line with the protection of human rights.

Preventive measures: Article 93 and the detection and transfer of proceeds

What caused controversy was the wording of Article 93 on including property and assets in the detection of transfers of proceeds of crime derived from illicit gains. Several delegations (e.g. Pakistan, China, Cabo Verde) supported this proposal. At the same time, other delegations (e.g. EU and its member states, UK, USA) opposed the inclusion of Article 93 in its entirety as it does not fall under the scope of the convention. Namely, the US delegation stated that they do not support any of the edits to Article 93 as they wish to delete it and replace it.

Essentially, Article 93 would oblige states to implement measures that would enable them to obtain from financial institutions the identity of customers and beneficial owners when there is suspicion of their possible involvement in the commission of transfers related to cybercrime.

If such a provision were to be adopted under the convention, it would also cover digital assets as proposed by Singapore’s delegation, which defined them as:

‘Any natural or legal person, excluding central banks and other state-backed authorities that issue digital currencies, that conducts one or more of the following activities or operations for or on behalf of another natural or legal person:

(a) Exchange between virtual assets and fiat currencies

(b) Exchange between one or more forms of virtual assets

(c) Transfer of virtual assets

(d) Safekeeping and/or administration of virtual assets or instrumentsenabling control over virtual assets

(e) Participation in and provision of financial services related to an issuer’s offer and/or sale of a virtual asset.’

Conference of (state) parties as a mechanism for implementation

Additionally, Canada proposed that the Conference of the State Parties should adopt rules in accordance with the principles of inclusivity, transparency, accountability, efficiency, and effectiveness. Some delegations (e.g. USA, UK, Canada, Australia) proposed that the ‘Conference of the State Parties’ should take into account the ‘time and location of the meetings of their relevant international and regional organisations and mechanisms, including their subsidiary bodies, and treaty bodies’.

Next steps

The next step is the ‘zero draft’ of the future convention to be prepared by the Chair and presented to the delegations this summer. The next AHC session will take place from 21 August to 1 September 2023. The concluding session is scheduled for early 2024.

However, the ‘devil’s in the details’ is exactly how the text-based negotiations in the AHC can be described: the fundamental provisions, such as the scope of criminalisation and the definitions, are yet to be discussed. It has been evident from the very beginning that delegations have opposing views, and it is not clear whether states will be able to reach a consensus in this regard.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!