Six months into 2017, the digital weather remains unsettled. Various crises brought occasional storms. Internet growth and innovation triggered a few sunny spells. The digital weather remains similar to the annual forecast for 2017.

This mid-year review provides an analysis of the main policy trends. It is based on the GIP Digital Watch observatory’s ongoing analysis of digital developments, summarised during the GIP briefings on the last Tuesday of every month and the Geneva Digital Watch newsletter.

For each of ten major trends, the number in brackets indicates their original ranking in January 2017. Each of the trends includes what to expect in Internet governance until the end of the year.

1. (10) Digital realpolitik: from values to interests

Realpolitik dominated digital policy since the start of the year. Interest and power came into sharper focus. Major actors are adopting ‘bottom line’ positions on money or power.

Governments worldwide are taxing the Internet industry and imposing fines for monopoly practices. The Internet industry cannot be shielded any longer by the narrative of being a ‘different’ part of the economy. Tax authorities are following the creation of value in the digital economy and looking for ways to increase tax income. From 1 July, Australia is applying a 10% goods and services tax on digital products and services from overseas that are bought in Australia. When they cannot tax directly, governments are tending to strike tax deals as Italy and Indonesia have done. In the anti-monopoly field, the major development was the European Commision fine of €2.42 billion against Google for non-compliance with EU antitrust rules.

The first six months reinforced the trend of shifting from global discussions towards bilateral deals and plurilateral arrangements (Figure 1). This trend is already noticeable in the area of cybersecurity, where the last two years saw a fast growth in bilateral agreements and plurilateral arrangements (e.g. G20 states agreeing not to conduct economic cyber-espionage against each other).

As it is typical for any realpolitik, citizens are becoming less relevant in digital realpolitik. They are personally targeted in advertising and surveillance efforts by corporations and governments. Individuals per se are getting lost in big numbers. The individual is just one amongst billions of Facebook users, and just one amongst billions of contributors to Google searches. Governments are increasingly speaking about digital sovereignty and less about the empowerment of individuals. Citizens are becoming more and more the object of digital growth and less and less the engine behind it, as it has been since the early days of the Internet.

On a promising note, realpolitik provides a more realistic picture of interests and risks as well as winners and losers resulting from Internet developments. It is in this way that realpolitik can contribute to creating the basis for more solid and sustainable Internet development.

What to expect?

Governments are likely to continue striking deals with Internet companies in order to recuperate some taxes. The bilateral deals could be the building blocks for a more structured approach to revenues from the digital economy. Follow Taxation updates on the observatory.

We can also expect more bilateral, regional, and plurilateral deals, especially on cybersecurity and e-commerce. For example, some countries are arguing for a plurilateral deal on e-commerce at the WTO Ministerial Conference in Buenos Aires later this year.

2. (1) Cyber geopolitics: between conflict and cooperation

The cyber-driven tension between the USA and Russia has dominated cybersecurity discussions since the beginning of the year. Globally, ransomware attacks, and increasingly sophisticated attacks by cybercriminals, have been a major concern.

See more: Wikileaks discloses the CIA hacking arsenal. New ransomware infects hundreds of thousands of computers around the world.

The search for cyber stability and certainty continues. While cybersecurity has featured strongly in most international meetings, we are far from reaching concrete solutions that can properly address cybersecurity risks.

Global level

On the global level, the fifth UN GGE failed to achieve consensus on a final report at its last session in June. Questions, such as what options states might have to respond to cyber-attacks, and if and how to take the cybersecurity process further under the UN, remain open. It seems, however, that discussions are still on the table, and as the UN GGE Chair recently indicated, there are still some options to be explored towards a possible compromise.

See more: UN GGE: Quo Vadis? (Digital Watch newsletter, Issue 22, June 2017)

At the G7 summit, the Taormina communiqué does not mention cybersecurity explicitly, but refers to the leaders’ commitment to ‘work together and with other partners to tackle cyber attacks and mitigate their impact on our critical infrastructures and the well-being of our societies’.

Cyber issues achieved higher prominence at the G7 Foreign Ministers meeting (10–11 April 2017, Lucca, Italy) which adopted two important documents. The first document, a Joint Communiqué, recognised the risks for critical infrastructure as well as for interference in democratic processes. It acknowledged the applicability of existing international law in cyberspace, including taking measures against wrongful acts, and invited states ‘to publicly explain their views on how existing international law applies to States’ activities in cyberspace to the greatest extent possible’. The second document, the Declaration on Responsible States Behavior in Cyberspace reminds states that international law also provides a framework for responses to attacks which are under the threshold of armed attacks. It underlines that ‘the customary international law of State responsibility supplies the standards for attributing acts to States, which can be applicable to activities in cyberspace.’

The G20 Leaders’ Summit in Hamburg, Germany (7–8 July 2017) that focused mainly on digital economy, also made reference to cybersecurity.

The Astana Declaration from the Summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (7–8 June 2017) reinforced a request for an international legal instrument in the field of cybersecurity.

National level

In the United States, President Trump’s cybersecurity executive order (11 May 2017) highlighted three key strategies: moving government services to a cloud, implementing a set of cybersecurity best practices known as the NIST Framework, and developing plans for protecting critical infrastructure. The executive order was criticised, however, for not addressing key issues, such as the security of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, data breaches, or responsible disclosure of vulnerabilities – issues that could have a major impact on the global IoT market, and users around the world.

The international cyber strategy that the State Department was supposed to prepare by late September as part of the cyber executive order will likely be delayed after the announcements that the cyber office of the State Department might be downgraded, and that the US coordinator for cyber issues Christopher Painter is leaving his job.

In China, a new cybersecurity law came into force on 1 June 2017. The law has special provisions on countering cyberthreats, hacking, and terrorism. The main criticism was about requirements related to security reviews and data storage in Chinese territory that could discourage foreign companies from operating in China.

Bilateral and regional

Trends towards bilateral and regional cyber arrangements have continued. In addition to a growing number of bilateral cyber agreements, we observed an increasing dynamism at regional level in, for example, the OSCE, ASEAN Regional Forum, Organisation of American States, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. It remains to be seen how the shift from multilateral to bilateral/regional approaches will affect the Internet industry, which is global in its outreach and market approaches.

Private sector initiatives

A new shift in digital policy came from the private sector, which started supporting international conventions and rules. Microsoft proposed the adoption of a Digital Geneva Convention consisting of three main segments: the substantive rules, principles for the engagement of technical sector, and an attribution organisation for assigning responsibility for cyber-attacks. Google proposed new norms for providing digital evidence to foreign governments. This would allow law enforcement to request digital evidence directly from Internet companies, thanks to bilateral agreements with the USA, bypassing the need to go through the Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT) – the traditional diplomatic channel for requesting international cooperation.

What to expect?

Discussions on the future of the UN GGE are wide open. In October, the First Committee of the UN General Assembly will discuss the next steps in global cybersecurity policy. The various proposals range between two major positions.

On one hand, mainly OECD countries will argue for continuation of the UN GGE work aimed at addressing how existing international law applies in the cyber domain. Even among OECD countries, there are divergent opinions on whether the UN should remain the main platform, or whether efforts should be invested in ‘the coalition of likeminded’ to explore options of responding to breaching the agreed norms, as the USA suggests.

On the other hand, mainly Shanghai Cooperation Organisation countries will argue for the establishment of an open-ended working group aimed at, eventually, drafting an international cyber convention with the new rules. Positions are very divided and it is not clear if and how compromise solutions can be found.

On 23 and 24 November 2017, The Global Conference on Cyberspace (GCCS) in New Delhi, India, will address cybersecurity issues in a comprehensive way. The GCCS aims to act as a track-two dialogue, bringing together high-level representatives of states, the corporate sector, and civil society. The Indian government announced the following priorities for GCCS 2017: ‘Goal of GCCS 2017 is to promote an inclusive Cyber Space with focus on policies and frameworks for inclusivity, sustainability, development, security, safety & freedom, technology and partnerships for upholding digital democracy, maximizing collaboration for strengthening security and safety and advocating dialogue for digital diplomacy.’ The GCCS’s track-two process may be supported through the work of the newly inaugurated Global Commission on Stability of CyberSpace (GCSCS), which looks into facilitating research and discussions about the possible options for future dialogue.

Microsoft’s proposal for a Digital Geneva Convention triggered a larger debate by drawing a parallel to the traditional Geneva Conventions, which focus on the protection of the individual in times of war. These developments create a context for discussion on the ways in which Geneva’s expertise and experience can help to ensure human-centred digital growth. In the autumn, this topic will be in the focus of series of research and policy discussions which will lead up to the 12th Internet Governance Forum (IGF) (18–21 December).

Follow at the GIP Digital Watch latest updates on the UN GGE, Cybersecurity, and Cyberconflict.

3. (8) Digital policy shaped by court decisions

In the first six months, a trend of courts-driven digital policy accelerated. Internet users and organisations increasingly referred to courts in the search for solutions to their digital problems. In the absence of rules customised to digital problems, judges are becoming de facto rule-makers in the field of digital policy.

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has already played a prominent role in the rulings on the right to be forgotten, the Safe Harbour framework, and mass surveillance.

It will play a similar role with regard to the sharing economy around the Asociación Profesional Élite Taxi vs Uber Systems Spain, S.L. case. On the main case, the question whether Uber is a transportation or an information society services company, the CJEU’s Advocate General’s opinion is that Uber is a transportation company. The final ruling on the Uber case is expected in the autumn.

Courts worldwide are busy dealing with other digital issues. Courts in Austria requested Facebook to remove legally prohibited content not only in Austria but also worldwide. Courts in Canada and France requested Google to remove search results worldwide for legally prohibited content. It prompted Google to ask if it is fair and appropriate for the national authorities of any single country to decide what should be accessed in other countries beyond their jurisdiction.

What to expect?

The CJEU’s decision on Uber will firmly establish whether the company is a transportation company. If the court upholds the Advocate General’s view, Uber and similar companies will have to obey all rules applying to, for example, taxi companies. We may also expect similar legal battles in other sharing economy sectors, such as rental and hotel businesses.

Check our Mapping Uber study as we update it with newer cases, and follow the latest updates on E-commerce, Jurisdiction, and Intermediaries.

4. (3) Content policy, fake news, and violent extremism content

Content policy has always been an important digital issue, impacting the role of intermediaries as gate-keepers and affecting basic human rights. In 2017, content policy debates have focused mainly on two areas: violent extremism content and fake news.

The need to combat violent extremism online exacerbated after terrorist attacks in recent years. Recent terrorist attacks in London and Manchester triggered major calls-for-action from governments. The Internet industry has come increasingly under fire for allowing the use of Internet platforms to spread violent extremism, and the recruitment and coordination of terrorist activities. The British Prime Minister called for new rules to deprive extremists of their safe spaces online, and the Australian Prime Minister requested Internet companies to react more promptly to requests from governments for access to encrypted information in the fight against terrorism and violent extremism.

See more: From October onwards, social media platforms with more than two million German users need to remove ‘obviously illegal’ content within 24 hours or risk a fine that could rise to €50 million.

In response to public pressure, several initiatives were created, such as joint campaigns by the UK and France, and initiatives by Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter, and YouTube.

See more: Internet companies join forces with French news organisations to combat ‘fake news’; Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter, and YouTube form a Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism, collaborating with the ICT4Peace Foundation to establish the knowledge-sharing network techagainstterrorism.org. The UK and France launch a joint campaign to combat terrorist content. Facebook talks about using both AI and human expertise to tackle online terrorism content.

In addition to violent extremism content, last year’s US presidential election triggered concerns over the surge in fake news and its spread through online platforms. Despite the furore in the USA, debates on fake news have so far taken a backseat in other parts of the world.

What to expect?

Governments worldwide are likely to increase responsibility of Internet platforms for content they host. Some proposals argue that social networks should be regulated like traditional media, such as newspapers and TV stations. This would impose strict rules on Internet companies, which they oppose, insisting that they act as neutral information providers. Another approach is to use special fines against intermediaries that host extremist and fake news, as was recently introduced in Germany.

A broader and longer-term approach, discussed at a few IGF 2016 workshops, is to focus more on improving social media literacy, which would help Internet users to validate information and build a more solid public debate space. Discussions are expected to continue at the 12th IGF in December, and at other policy events throughout the year.

Follow the upcoming events, and our page dedicated to fake news.

5. (6) Digital commerce and Internet economy

Digital commerce discussions have surged since the beginning of the year in the World Trade Organisation and G20 among other policy spaces.

Under the German presidency, the Declaration of the first G20 Meeting of Digital Ministers, held in April in Düsseldorf, Germany, accompanied by a roadmap, focuses on expanding access and developing a better digital infrastructure, alongside efforts to improve digital skills. The priority issues regarding digital trade include how to quantify digital trade, how to develop international policy framework for digital trade, and how to address the needs of developing countries.

The importance of digital commerce for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was highlighted in discussions during the UNCTAD e-commerce week. Technical advances, such as 5G, and the digital growth framework around them, remain critical to fostering mobile commerce. In the first half of the year, the emphasis was also on innovative technologies, such as fintech and blockchain applications. The growth of virtual currencies (BitCoin, Ethereum) has opened new policy and regulatory issues.

Internet giants came under closer scrutiny for competition practices in the online marketplace. Google was fined by EU regulators at the end of a long investigation finding a violation of the antitrust rules in shopping services. Facebook was also fined for lack of compliance with the EU merger rules, after announcing that it would combine its user data with that of WhatsApp, that it acquired in 2014.

In a pre-emptive regulatory attempt, the World Committee on Tourism Ethics (WCTE), in collaboration with TripAdvisor, Minube, and Yelp, designed Recommendations on the Responsible Use of Ratings and Reviews on digital platforms.

What to expect?

Digital trade will continue to increase in relevance in preparation for the WTO Ministerial Conference, 10–13 December 2017, in Buenos Aires. The tension remains between countries, mainly developing ones, which argue that it is premature to have more WTO rules on e-commerce, and mainly developed countries arguing that the growth of e-commerce must be supported by more robust WTO rules. These dynamics have shaped many digital trade discussions since the start of the year. An outcome of e-commerce discussion at the WTO Buenos Aires could be from, less likely, a full mandate to negotiate e-commerce roles via a plurilateral initiative to, most likely, the continuation of informal discussions on e-commerce leading towards developing an e-commerce roadmap in 2018.

In the EU, the digital single market is becoming one of the main engines for future integration. During Malta’s EU presidency, roaming charges were removed. Estonia, who presides in the second half of 2017, will focus on free data flows across Europe.

Follow more updates on our dedicated pages: E-commerce, Taxation, and E-money and virtual currencies

6. (2) Encryption: security and privacy

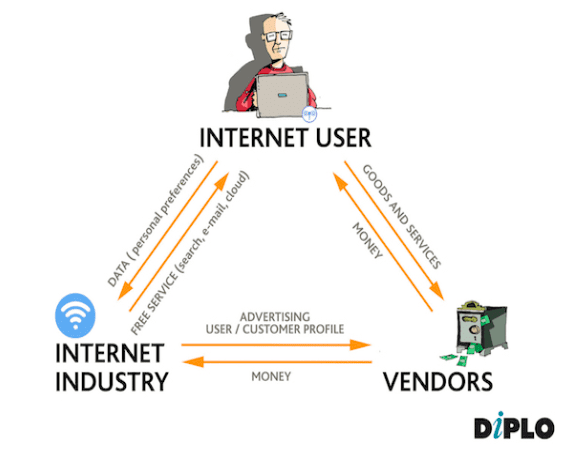

Encryption remains in focus of debates in academic and policy circles. Although we did not experience any crisis on the scale of 2016 Apple/FBI crisis, governments continue to exert pressure on Internet companies to provide backdoor access to user data or to reduce levels of encryption. The Internet industry continues to resist. User data is the industry’s main commodity, and losing user trust could endanger the business model (Figure 3). Some human rights organisations argue that the right to encrypt may be a derivative right of the basic human rights to privacy and freedom of expression.

Figure 3. Internet business model

In the first six months of 2017, the Internet industry started to look for more predictable and formal arrangements that would deal with governments’ requests for access to data in criminal investigations and the fight against terrorism. For example, Google proposed a new legal framework aimed at helping foreign governments to obtain digital evidence in a simpler, faster, and more organised way.

What to expect?

The pattern of increasing discussion after a major crisis and terrorist attack is likely to continue. It could lead towards developing national regulations that would request Internet companies to open a backdoor to access to encrypted communication. Faced with legal requirements and the risk of losing markets, Internet companies are likely to be more proactive in finding an acceptable compromise between using encryption for protecting privacy of users and answering requirements by investigators and security agencies.

This gradual evolution could be changed by a digital ‘Titanic moment’, a major global crisis triggered by a cyber-attack. Such a crisis could lead towards the adoption of new cybersecurity regulations analogous to what happened back in 1912, when the Titanic catastrophe led to fast adoption of the international regulation of radio-communication.

Follow the developments on our observatory: Encryption, and Privacy and data protection

7. (4) Powerful interplay: AI – IoT – Big data

The interplay among three technologies – artificial intelligence (AI), IoT, and big data (Figure 4) – has created a new dynamism since the start of the year.

Figure 4. Interplay between artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and big Data

(for more information visit https://dig.watch/ai)

Major Internet companies that process significant amounts of data (such as Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft) have increased their efforts to become prominent players in the field of AI. In addition, they have numerous initiatives aimed at AI and public good. For example, Microsoft launched an AI for Earth initiative and a Research AI lab. Facebook is using AI to tackle online content related to terrorism. Google has been undertaking research on issues such as addressing privacy concerns in AI solutions.

Governments also have become more aware of the significant potential that AI and the IoT have for development, and are looking into ways to support the evolution of these fields. China, for example, who has long supported research in the field of AI, has recently released a national AI development plan, intended to make the country the world leader in the field by 2030.

As the interplay between AI, the IoT, and big data becomes increasingly powerful, concerns are also growing about its implications for the economy, social welfare, privacy, safety and security, and ethics, among others.

There are more and more calls for guidelines and even government intervention to set the scene for how such challenges could be addressed. In a rather alarming way, Tesla CEO Elon Musk told US governors that AI ‘is a fundamental existential risk for human civilisation’, and that there should be proactive government intervention. While Musk’s views are seen by some as being too focused on future possible challenges rather than on current ones, he is not the only one asking for regulatory and legislative intervention.

In April, the UK’s Royal Society called for careful stewardship of machine learning (the technology that allows AI to learn from data) ‘to ensure that the dividends from [this technology] benefit all in the […] society’. A report issued in the same month by the International Bar Association Global Employment Institute argued that current labour and employment legislation needs to be adapted to an emerging AI-driven workplace. In June, researchers from the UK Alan Turing Institute published a paper stating that current regulations are not sufficient to address issues such as transparency and accountability in AI systems, and called for guidelines.

What to expect?

In 2017, the security and data implications of AI and IoT developments will be in focus for governments and industry (as already requested in the USA and planned by the EU). The main question is if industry standards and self-regulation will be sufficient to address the security challenges that the growth of AI and IoT open. If self-regulation will not be sufficient, it is very likely that governments will step in with liability regulation for IoT and AI, as they have done with cars, airplanes, and other technical devices that can endanger public safety.

Follow the updates on the observatory: Privacy and data protection, Internet of Things, Convergence, and AI trends

8. (5) Data governance and data localisation

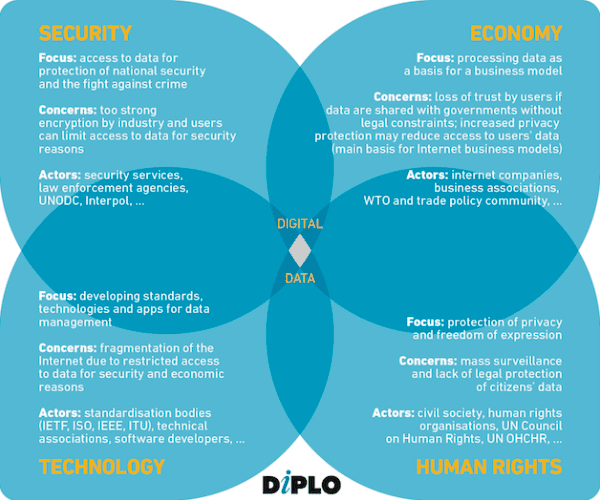

Figure 5. Interdisciplinary data governance

Data has become a salient issue in digital policy, with the realisation that data is at the centre of our online interactions, Internet business models, and negotiations related to privacy rights (Figure 5).

In Europe, the main dynamics is around preparation for 28 May 2018 when the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) will become enforceable. Businesses and institutions are gearing up to bring their practices in line with the rules. Since the GDPR’s applicability extends beyond the EU’s shores for data of EU citizens wherever they are located, pressure is also mounting on companies and institutions in other regions, amid strong fears that one year is a major challenge to bring practices up to speed with the new requirements.

Data continues to shape the Internet business model. The motivations for data localisation – the practice which requires service providers and/or the data they store to be located within national borders – include protectionist trade policy, national security considerations, protection of citizens’ privacy, and politically driven filtering.

What to expect?

Data flow and risks of data localisation will be in the focus of Estonian EU Presidency (July–December 2017). Throughout the rest of the year and in the first quarter in 2018, we can expect a major push – together with raised awareness – on the applicability of the GDPR and on how to get in line with the requirements.

Follow our updates: Privacy and data protection, Intermediaries, and Content policy.

9. (9) Connecting the dots among digital policy silos

Policy silos are becoming a major problem in developing effective digital policy. Namely, the multidisciplinary nature of digital policy (Figure 6) affects a wide range of policy areas beyond the digital sphere. For example, current discussions on data flows in the context of trade is both affected by and can affect human rights, security, and standardisation aspects of data policy. When it comes to human rights, the more privacy protection is requested, the less access to data for commercial purposes is possible.

Data flow is essential for national security and stability. For example, cutting access to Facebook or Google could affect the lives of millions with an enormous impact on social, political, and economic stability. Data standards specifying how data are used, stored, and exchanged can also affect the data-driven economy. Thus trade negotiations on data flow and e-commerce are not effective without taking into consideration human rights, security, and standardisation aspects of data policy. Similarly, the cross-silos policy impacts applies to most other digital policy issues.

For example, the IoT – previously tackled as a technological and economic issue – has received attention for its security vulnerabilities following recent cyber-attacks.

Figure 6. Multidisciplinary digital policy

There are ongoing discussions on ways and means to create interlinkages among different digital policy areas. The CSTD Working Group on Enhanced Cooperation addresses Internet public policy issues, including the question of their cross-cutting aspects. The Working Group will host the next meeting in September, on the way to submit its report in 2018.

The most evident need for overcoming policy silos is in the implementation of the sustainable development goals (SDGs). The Internet, as a common element for all SDGs, could also play an important role in connecting the dots among various SDGs.

The interlinkages among digital policy issues and various SDGs was one of the topics at the second Multi-stakeholder Forum on Science, Technology and Innovation for the Sustainable Development Goals, 15–16 May in New York; at the WSIS Forum, 12–16 June in Geneva; and at the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development, 10–19 July, also in New York. The WTO Public Forum, to be held in Geneva, 26–28 September, will most likely address Internet-related topics at their intersection with trade and commerce. At the end of the year, the 12th IGF will feature many discussions underlining the interconnections between the various Internet governance and digital policy issues.

What to expect?

Any action should recognise the reality that policy silos are here to stay. E-commerce is discussed in the WTO. Online privacy is discussed in the UN Human Rights Council. Standardisation issues are discussed in the Internet standardisation bodies. Starting from reality of policy silos, initiatives should focus on ‘boundary spanners’ that will create the necessary linkages and convergences. ‘Boundary spanners’ could emerge in various contexts from individuals and organisations that could link a few policy areas (e.g. trade and Internet governance) to nudging new processes (requesting multidisciplinary workshops at Internet governance forum) and supporting multidisciplinary research and information analysis. Follow the updates: SDGs and the Internet, and the Internet Governance Forum.

10. (7) ICANN after the IANA transition

ICANN has had a rather quiet time since the start of the year. This is a continuation of the trend that started with the completion of the IANA stewardship transition (1 October 2016), which transferred the supervision of the IANA functions from the US government to the global multistakeholder community. While the surface appears calm, the underlying tensions remain. As the entity responsible for the overall coordination of the domain name system (DNS), ICANN deals with the question of online identities (as reflected in top level domains – TLDs), which is likely to remain a controversial policy issue. In addition, ICANN’s governance construct has numerous ‘constructive ambiguities’, which may remain constructive or turn into conflict and crisis (e.g. relations between the Governmental Advisory Committee (GAC) and ICANN’s Board).

Following the transition, the Cross Community Working Group on ICANN Accountability (CCWG-Accountability) has continued working on additional mechanisms to help ensure that ICANN is fully accountable to the global Internet community. The level of accountability will be perceived as a half-empty or half-full glass, depending on the views of various actors about ICANN.

The discussion on jurisdiction within the dedicated sub-group of the CCWG-Accountability focused on two main issues: relocating ICANN from California to a new jurisdiction, and providing total/partial immunity to ICANN. Reports from the most recent ICANN meeting show that it is unlikely that there could be a consensus position in the group on these issues, which probably means that the current status quo will be maintained.

We also said in January that ICANN would focus on new gTLDs over the year. This has proven to be the case at the first two ICANN meetings in 2017: ICANN58, 11–16 March in Copenhagen, Denmark; ICANN59, 26–29 June in Johannesburg, South Africa. And it shows that, after the lengthy IANA stewardship transition process, the organisation is now strongly re-focusing on its policy development work.

What to expect:

On the identity agenda, intense debates have already resurfaced over the .amazon gTLD. In 2014, the ICANN Board decided to reject the application for .amazon, submitted by the Internet company Amazon, owner of the trademark Amazon. The decision was made based on advice from the GAC, which objected to .amazon being delegated to the company. The objection relied on the view of countries of the Amazon River Basin, which have been arguing that the name and domain ‘Amazon’ belongs to people and countries of the Amazon region.

On 11 July 2017, an Independent Review Panel (IRP) recommended that the ICANN Board re-evaluates the application for .amazon. This report will trigger a response by Amazon Basin countries and will lead to intensification of the discussions on several sensitive issues, such as the protection of geographical names and the relations between the GAC and the ICANN Board and the rest of the ICANN community. The ICANN Board’s decision with regard to the IRP recommendation will be one of the major ‘stress tests’ of the new ICANN governance architecture.

Discussions on jurisdiction-related issues will continue without clear consensus or compromise in sight. Considering the concerns raised by several governments at the recent ICANN meeting in Johannesburg, it is expected that the GAC will suggest broader cross-community discussions on these issues.

When it comes to ICANN’s policy development processes, the topics that will likely be mostly debated in the upcoming months include registry and registrars compliance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation, the revision of the WHOIS policy (the so-called Next-Generation gTLD Registration Directory Services), and the review of the new gTLD programme.

Follow the updates: The new generic top-level domains | IANA transition and ICANN accountability | Domain Name System | Root zone

Follow-up

The GIP Digital Watch observatory will continue to provide comprehensive and just-in-time coverage of major Internet governance trends and events. A few tools can assist you in following the busy digital agenda.

Firstly, you can use DeadlineR – available on each event page – in order to ensure that you do not miss important deadlines prior to major events (submitting workshop proposals, registration, etc.). DeadlineR will remind you via e-mail about important deadlines.

Secondly, the Geneva Digital Watch newsletter will provide you with a monthly summary of major Internet governance and digital policy developments. You can subscribe to the GIP news mailing list to receive notifications about new issues of the newsletter.

Thirdly, on the last Tuesday of every month, at the monthly briefings, we give a ‘zoomed-out’ update of the major digital developments from the previous month. Register and join us for the next monthly briefing on 29 August 2017.

What relevance do the 10 trends have in your region? Are there other trends that are more prominent in your country or region? Comments are welcome.