Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

The year 2025 will be a landmark year for digital diplomacy and global governance. It is the year of wrapping up the UN cybersecurity OEWG and the negotiations on cybercrime at the Ad Hoc group. It’s the year UN member states will decide on the future of the World Summit of Information Society process and the Internet Governance Forum (IGF). 2025 will also flag the ‘last mile’ toward the realisation of the Agenda 2030 and 17 SDGs that are increasingly dependent on digital developments.

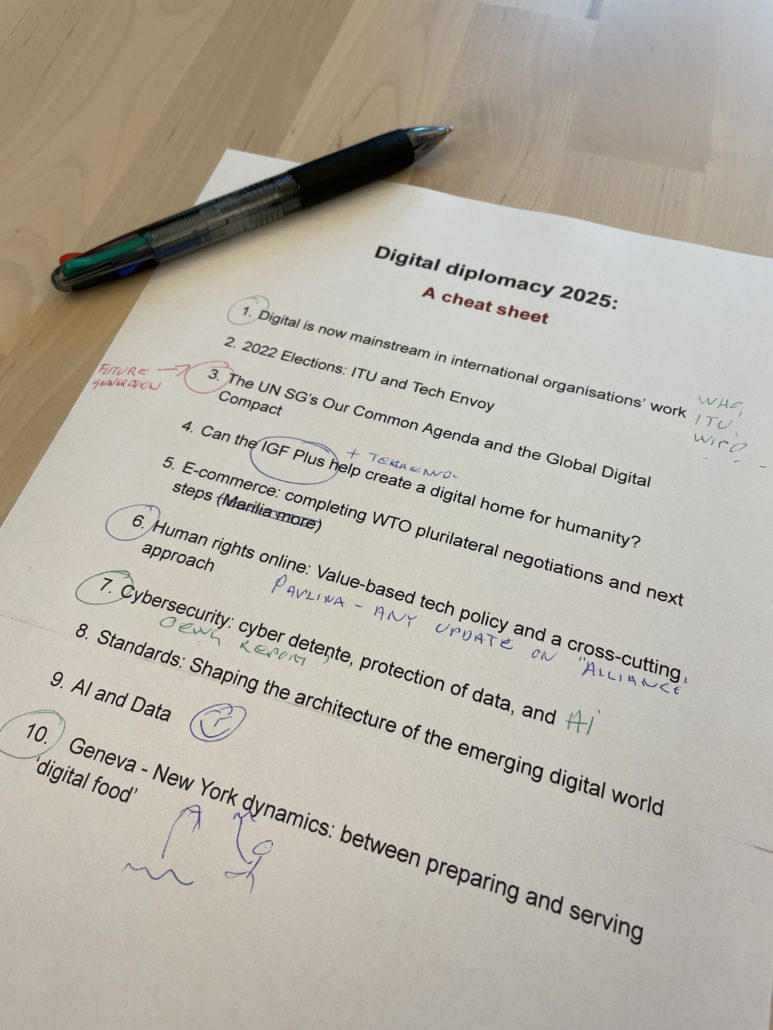

The cheat sheet below should help diplomats navigate better the next few years in global digital governance.

This 2025 cheat sheet helps place current digital developments in a wider policy and time perspective. It reflects the trends of the 2020s and builds on our annual prediction for 2022.

While keeping 2025 in mind you can follow daily developments at the Digital Watch which provides comprehensive coverage of trends, processes, events, topic analysis together with monthly briefings, newsletters, and weekly digests.

Contents

ToggleE-trade is becoming just trade. Digital health is just health. Cybersecurity is security. As prefixes digital/cyber/e/tech will gradually disappear, technology’s impact increases in shaping the work of international organisations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), World Trade Organization (WTO), and International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

The mainstreaming of digital at the UN is becoming increasingly visible under three main areas of global diplomacy: peace and security, economy and development, human rights and humanitarian assistance.

Mainstreaming digital in multilateral diplomacy will impact the modus operandi of international organisations and the diplomatic community in New York, Geneva, and other key multilateral hubs. Hence, diplomats and officials have to continuously develop boundary-spanning knowledge and skills to cover policy issues from various policy perspectives reflecting the cross-cutting impact of digitalisation on society. The illustration below shows the various policy perspectives using data governance as an example.

Ministries of foreign affairs and international organisations need to catch up to this transition fast by: (a) adapting their internal organisations, (b) connecting various digital issues by starting to think in terms of digital foreign policy, (c) and preparing diplomats to become boundary spanners between technological and traditional diplomacy and policy.

The road to 2025 will be impacted by elections and nominations in 2022. The new International Telecommunication Union (ITU) leadership will be elected in autumn. Two candidates, from the USA and Russia, are leading the competition for the position of ITU Secretary-General. Elections are being held also for the Deputy Secretary-General, and the Directors of the three sectors: the Radiocommunication Bureau, the Telecommunication Standardization Bureau, and the Telecommunication Development Bureau. The major task for the new ITU’ leadership will be to adjust the ITU’s role to the fast changing digital and communications realm.

In the coming months, the UN Secretary-General (UN SG) will nominate a new Tech Envoy as envisioned in the UN Secretary-General’s Roadmap on Digital Cooperation in 2020. The new Tech Envoy will have the complex task of shaping this new role and navigating an increasingly complex digital and cyber policy space shaped by the tech industry, member states, UN organisations, and emerging actors such as crypto and online gaming communities.

Digital issues will play a significant role in UN SG’s Our Common Agenda‘ process. The Global Digital Compact should be a part of the Future Declaration to be adopted by the Summit of Future in September 2023.

It is not yet clear how the Global Digital Compact will be drafted. There are many contributors and there is no shortage of initiatives and proposals on digital, AI, and cybersecurity in the UN and beyond. Drafters should harvest them and bind them together with complementary initiatives at the UN set by the UN SG’s Roadmap. The new digital compact should cover ‘traditional’ issues such as Internet infrastructure, cybersecurity, online privacy but also foresee issues such as passing digital heritage to future generations and an interplay between environment and digital.

Drafting of the Global Digital Compact should incorporate a significant capacity development aspect in helping countries worldwide to develop their digital foreign policies and priorities.

The IGF remains the only place in the UN system that could become a ‘digital home of humanity’. It has the legitimacy of the UN system which will be critical for the buy-in of digital governance proposals, especially from small and developing countries. A key challenge for many of these countries is to contend with the proliferation of businesses, academic content and other governance initiatives in the digital realm. The IGF can serve as a ‘one stop shop’ for addressing a wide range of issues from access or cybersecurity to AI.

The IGF mandate as outlined in the article 72 of the WSIS Tunis Agenda provides considerable flexibility to create an inclusive space which can accommodate a wide range of views and inputs and galvanise ideas and proposals in joint interest.

Paradoxically, this very strength of the IGF, its adaptive and legitimate structure, is its weakness. Throughout its history, the IGF has been criticised by both those who would like to see the Internet governed by inter-governmental organisations and those who do not want to see any UN involvement in digital governance. Heated debates on the future role of the IGF are likely to continue. Some issues will figure strongly: transparency of participation, the possibility of adopting policy outcomes (e.g. recommendations), and balanced influence of stakeholders.

Any more prominent role of the IGF will require more visibility for the IGF which could be facilitated by the yet-to-be-created IGF Leadership Panel. Strengthening the IGF will require a lot of political and diplomatic wisdom. It needs to be inclusive, more effective and create the right interplay between bottom-up inclusion and top-down leadership.

IGF and civil society

Global politics will become more geopolitical, which will adversely affect civil society participation in global governance. This places the IGF under greater pressure not only to maintain a civil-society-friendly space but also to expand inclusion to marginalised groups, especially those from small and developing countries.

Possibly, the biggest ‘problem’ in the formal IGF provision lies in its title. The term ‘Internet’ from 2005 has become a misnomer for our days. ‘Digital’ governance forum would better represent the current focus of the IGF.

In the next few years, the WTO will be under pressure to deliver negotiated results on a wide range of issues, while preserving its multilateral characteristic. Several important topics, such as e-commerce, trade and environment, and investment facilitation are being discussed under ‘Joint Statement Initiatives (JSIs)’, which only involve a subset of the WTO membership. Some WTO members see JSIs as key mechanisms to make progress on trade liberalisation, while others argue that JSIs weaken multilateralism at the WTO.

The focal point of this tension will be the JSI on e-commerce, which includes not only core trade issues, such as trade facilitation and market access, but also a wide range of digital policy issues, such as data flows, data protection, cybersecurity, and spam.

Data flow and data governance are critical issues in JSI and other e-commerce negotiations. They will revolve around three positions: China, the EU, and the USA. The USA strongly supports data flows and opposes data localisation. EU supports data flows without restrictions, privacy protection being an exception. China supports economic data flow with countries self-judging the exception on the basis of national security and public order.

If members of the JSI on e-commerce overcome divergences on key issues, such as data flows, this would strengthen the belief that JSIs could be used as a mechanism to overcome multilateral deadlocks. At the same time, this would bring the risk of further alienating countries who did not take part in the JSI on e-commerce – Africa and the Caribbean are notably underrepresented – and the countries that generally oppose JSIs as a mechanism for advancing negotiations at the WTO, such as India and South Africa.

Whether or not an agreement is achieved at the JSI, the most important negotiations on e-commerce will continue to happen outside the multilateral system, in the context of preferential trade agreements (PTAs). The governance of e-commerce is increasingly reliant on a few countries that have become legal powerhouses, notably Singapore, Australia, and Japan. The shift to the Asia-Pacific is accompanied by a persistent disconnect of developing countries from the network of agreements that have shaped digital trade. The advancement of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) could be a game-changer in years to come, pulling the centre of gravity of e-commerce policy towards the Global South, and creating the possibility for African countries to contribute to norm-shaping at the global level, backed by their regional weight.

Values and human rights are pillars of the US foreign tech policy. The EU, Australia, Japan, Switzerland, Netherlands and other countries increased the relevance of human rights in their international tech initiatives.

This interplay between tech issues and values will become prominent in activities of international human rights bodies such as the UN Council on Human Rights (UNCHR). It will happen in four main ways.

First, the focus will continue on specific human rights such as freedom of expression and right to privacy online mainly via activities of special rapporteurs. Second, other human rights such as freedom of assembly, cultural and development rights will achieve online relevance. Third, more on cross-cutting interplay between different human rights such as impact on online privacy for freedom of expression, diversity, culture, education and many other fields. Fourth, there will be a greater interplay between human rights and digital standardisation, e-commerce, cybersecurity and other related fields.

The Human Rights Council 2019 resolution on ‘New and emerging digital technologies and human rights’ which was followed up by 2021 an Advisory Committee study in 2021 will be important in shaping new relevance of human rights for digital developments.

As digital or cyber is increasingly becoming a national security issue, this will be reflected in negotiations in the UN system. Two processes are under the spotlight: (a) the UN Open-ended Working Group (OEWG) on cyber, under the first committee as a follow-up of former UN GGE and the ongoing OEWG with a mandate to further clarify the applicability of international law to cyber, develop cyber norms, and work on their implementation till 2025, (b) the Ad-hoc Committee on cybercrime under the third committee, mandated to develop a draft global treaty by 2023.

We can also expect new initiatives to emerge under the UN and other multilateral fora, which will bring additional ‘securitisation’ of digital policy issues; such as the French-Egyptian proposal on Programme of Action, and the Chinese initiative for data security. Regional organisations, like the Organization of American States (OAS), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and the African Union will further develop their frameworks, including confidence and capacity building initiatives.

Given the global dynamics of international relations, there is no doubt that the ‘securitization’ of digital governance will continue. But, the challenge lies in maintaining a balance between security aspects and other aspects in digital cooperation in development, humanitarian assistance, environment protection, and human right.

As it is very difficult to get international legal arrangements in the digital realm, digital standards will rise in relevance as ‘soft law’ and as a practical tool for governing digital space . Digital standards will increase in relevance not only in the production of hardware and software, but increasingly in the way digital technology is used – e.g. standards for dealing with AI biases, standards for ensuring sound cybersecurity procedures, and so on.

However, traditional standardisation organisations will face challenges in keeping up with the fast pace of tech development, and there is the growing appetite of the private sector to shift their attention to various industry and tech community fora that set de facto standards.

With increasing awareness about the geopolitical relevance of standards, various countries and blocks will attempt to embed their values and governance models into technological standards – in particular, those developed at the international level.

The principal risk is the fragmentation in digital standardisation caused by current geopolitical tensions. The internet will eventually become fragmented, if that happens.

AI and data governance have been fashionable topics in global governance. As the number of initiatives and proposals on AI and data continue to grow, the main challenge is how to ensure some convergence among them.

Firstly, confusion could be reduced by addressing data and AI together as two sides of the same governance ‘coin’. AI is built on data. Thus, data governance – from privacy to international data flows – directly impacts AI governance.

Secondly, it is important to build more convergences around a few processes that have been gaining some traction. On the question of values and human rights, the UNESCO recommendation on the ethics of AI, and the ongoing work at the Council of Europe (CoE) on a potential legal framework for the development, design, and application of AI are prominent. In the field of sustainable development, it is the ITU’s AI for Good initiatives. Developments at the level of the GGE on emerging technologies in the area of lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS) are also worth following, although the process seems rather stalled at the moment.

Typically, after negotiations on technical issues in Geneva, diplomatic arrangements are politically adopted in New York. This Geneva – New York diplomatic interplay will get new twists ahead of 2025.

Firstly, digital diplomacy dynamics in New York are new, especially when compared to more than a century-long tradition of tech negotiations in Geneva. Many small and developing countries will have some diplomatic and technical expertise in Geneva developed by following ITU and other technical organisations. Typically, such expertise does not exist in their missions in New York. Thus, any major shift towards digital negotiations in New York will further widen the policy inclusion gap between developed and developing countries.

Secondly, highly cross-cutting aspects of digital governance will be difficult to automatically replicate in New York. Unlike traditional political issues, such as security, digital governance requires standardisation, economic, human rights, and security inputs. Many countries attempt to overcome this challenge through their missions at Geneva. To create these holistic dynamics in New York’s diplomatic ecosystem, it would take more effort.

For more information about the Geneva digital ecosystem you can consult Geneva Digital Atlas.

You should endeavour to look beyond your exclusive policy area whether it is cybersecurity, AI or human rights. It will not be easy in the face of more and more specialisation on narrower policy issues.

When you inevitably dig deeper in specific digital governance fields, you should at least try to avoid not seeing ‘the wood for the trees’! Digital governance and diplomacy must follow the very nature of digitalisation which bypasses traditional divisions in economics and politics.

Thus, ahead of us, the critical role will be that of the boundary spanners who can bridge different policy silos from technology to human rights and the economy. A holistic approach to digital governance is apparent in Swiss Digital Foreign Policy and recent US State Department organisation for digital diplomacy.

The critical formula for digital governance ahead of 2025:

The more countries cover digital issues holistically,

the better they will promote and protect their tech interests internationally.

You can gain new skills and knowledge to deal with digital governance and diplomacy by following Diplo’s courses based on holistic pedagogy.

Tailor your subscription to your interests, from updates on the dynamic world of digital diplomacy to the latest trends in AI.

Subscribe to more Diplo and Geneva Internet Platform newsletters!

Diplo is a non-profit foundation established by the governments of Malta and Switzerland. Diplo works to increase the role of small and developing states, and to improve global governance and international policy development.

Greetings

Dear Dr Jovan

Reference to the message on the subject.

So good to hear from you. I hope you are well and in good health. Thank you for the information. Appreciate it.

Then I have taken the opportunity to read the whole document. Interesting and informative document on the subject.

Please accept my sincere gratitude and feel free to contact me or my team at team@isdrc.net on the subject. If any

Asif Kabani MBA Mentor, Keynote Speaker and Senior Fellow UN 🇺🇳 Founder and CEO, ISDRC – Next Generation Leaders, Europe LinkedIn: https://linkedin.com/in/kabani