To what extent does an independent diplomatic culture exist which permits diplomats to exert their own influence on the conduct of international relations? Insofar as such a culture exists, what does it look like, is it a good thing and, if it is, how is it to be sustained? To answer these questions, I will begin by exploring what we generally mean when we talk about culture and how we see culture operating in contemporary international relations. I will then sketch out the basic elements of a diplomatic culture and discuss different accounts of its origins. The main argument of this paper is that something we may call a diplomatic culture arises out of the experience of conducting relations between peoples who regard themselves as distinctive and separate from one another. The production of this culture by experience, however, can benefit from the right sort of diplomatic education and training. This help is greatly needed because diplomats are also shaped by other cultures whose preoccupations are rarely consistent with the requirements of good diplomacy.

The Idea of Culture

Bozeman refers to culture as a “common language, a common pool of memories, and shared way of thinking, reasoning, and communicating,” while Der Derian suggests that it is conventionally seen as a people’s “common stock of ideas and values.” 1Bozeman, “The International Order in a Multicultural World,” in The Expansion of International Society, ed. Hedley Bull and Adam Watson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), 387; and James Der Derian, “Hedley Bull and the Idea of a Diplomatic Culture,” in International Society after the Cold War, ed. Rick Fawn and Jeremy Larkin (Houndmills: Macmillan, 1996), 88). Thus, we see the term used to refer to a set of attributes, each of which may or may not have causal or explanatory power, and to suggest a force in its own right. In both senses, culture is seen as important in international relations, but this is a relatively recent development. Formerly, culture was either ignored or treated as an accent which might modify expected behaviour and surprise policymakers if they had not made allowances for it. The rigidities of Soviet bargaining techniques or the pretensions of French grand strategy, for example, would lose their wrong-headed character once one put on one’s culturally sensitive spectacles. The basic rationality common to us, it was maintained, would then reappear.

How are we to account for culture’s neglect and subsequent elevation? Three lines of explanation for its neglect suggest themselves: those which distinguish between relations inside polities and outside them; those which are sceptical of the idea of culture itself; and those which assume that beliefs are easily subjected to the tests of reason and evidence. “Inside/Outside” arguments assert that most political, social and cultural life is lived inside polities, between which only simple relations are conducted in a thin or absent cultural context. Indeed, this thinness or emptiness, it was argued, gave international relations their distinctive quality. Realists saw the international arena as a social vacuum filled only by hot air or fragile utopian projects that always succumbed to considerations of power and national interest. Liberals asserted that power and interests could generate some international rules and a sense of obligation to them, but that both remained circumscribed and prudential in character. Anything stronger depended on the moral afterglow of a previously existing community, Christendom in the case of western Europe, for example. Radicals acknowledged various conceptions of a cosmopolitan world culture, but this existed only immanently or in principle, and certainly not yet. Even for them, culture remained primarily an “inside” phenomenon until the advent of some kind of revolutionary transformation.

Scepticism about the idea of culture itself may be expressed in analytical or political terms. It may be objected that according to typical definitions like the ones above, everything is culture. This may be true, but it is not very useful for explaining things, and it seems to ignore the fact that individual human beings may have uneven and limited liability commitments to the cultures of the societies in which they live. It may be that by calling sets of ideas, values and associated behaviours a culture, we assign existence and explanatory power to something which, properly speaking, does not exist and, in so doing, obscure the real explanations for why a set of people seem to think, believe, and act in a certain way. Belief in cultures may have real consequences for people for what they do, in much the same way as children’s beliefs in Father Christmas, but Father Christmas does not exist, and no one should argue in any way which suggests otherwise. They do, however, and this provides the ground for political scepticism about the idea of culture. In this view, culture claims may be no more than political moves by the relatively weak. The strong do not justify what they want or resist the demands of others on cultural grounds. They employ reason, righteousness, interest and, when all else fails, necessity and power. It is the weaker party that argues that they do what they do because they are who they are, and claim that cultural arguments are trumps, because they have nothing else, not power, reason nor, perhaps, even justice on their side.

Finally, the concession that the elements of culture and the idea of culture operating as a whole may both have material consequences has usually been accompanied by an implied corollary. Beliefs which cannot be rationally sustained in the face of the available evidence will lose their force among reasonable people. To this might be added the belief that the world in which we all live is providing ever more vigorous tests of unsustainable beliefs and other incentives for not adhering to them. The long-established view, therefore, was that we should expect particular cultures to fail under the pressures of modernization and the idea of culture itself to fade into no more than a signal of secondary accents on an increasingly common form of life.

The Revival of Culture in Contemporary International Relations

None of this seems to have come to pass. Instead, culture appears to be at the centre of contemporary discussions of international relations. There are great debates about whether civilizations – transnational cultural communities of understanding about the world and how people ought to live in it – are more important actors than states in world affairs. Concerns are expressed about the possibility for real understanding between peoples trapped in their respective culture worlds. And, overshadowing all, is the sense that some single, global culture may be in the process of transforming everything. In all these debates, culturalists currently hold the initiative. Sceptical policymakers and scholars alike who maintain that the commonalities of human experience outweigh the differences are told that this claim is itself culture-bound, as is the idea of globalization which they thought was eroding those differences which exist.2 Samuel Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations (Touchstone, Simon and Schuster, 1997); Negotiating Across Cultures (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, 1997), and Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Random House, 1999).

How is all this to be explained? One conclusion that most of us are tempted to entertain is that people in general are more stupid than we thought and less brave than we hoped. Under pressure, they cling to old beliefs even when these are proven wrong and counterproductive. Ruling such people, elites which can only justify themselves in cultural (i.e., unreasonable and irrational) terms turned out to be stronger than previously assumed and have not had to rely on raw power. In this view, then, there has been no rise of culture, even if people talk about it more, because the idea is necessarily epiphenomenal in relation to more important things. Even in rationalist terms, this is probably a poor explanation based on a misreading of the incentives under which people operate and judgements about what ought to be important to them. A better one suggests the possibility that the march of reason and modernity in the world is itself a primary catalyst of culturally-based reactions. This march presses people to define who they are and make explicit what was previously implicit in their ways of life in response to it. If this is so, then it suggests problems with the idea of human beings as rational cores with cultural accents. Either assigning reason to the core and culture to the periphery of individuals and societies, or the weights assigned to the rational core and the cultural periphery may be mistaken.

Irrationalists favour the former, assigning a capacity for some sort of calculation to the edges of beings driven by more primary impulses and commitments. Culturalists tend to the second formulation, seeing our reasoning capacity taking place within cultural perimeters which settle many of the big questions for us a priori, and of which we are barely aware until they are challenged.

“Big” Cultures

Mistakenly or not, however, the idea of culture has taken hold in international relations, in terms of what will be referred to here as “big” cultures or civilizational projects embodying claims about what the world is like and how people ought to live in it. At the highest generality, people speak of a global or world culture. They have always done so in the sense of an underlying, cosmopolitan set of values which human beings have been claimed to share whether or not they are aware of the existence of each other. In addition, a surface or even superficial global culture is said to be coming into existence for a variety of reasons. These range from the need to address economic and environmental problems which may be solved only by the efforts of all, to the emergence of worldwide patterns of consumption and their associated fashions. In this view, the common skills, appetites, loyalties and disciplines required by industrial modernization which, Gellner once maintained, were provided by the creation of national populations within territorial states, now have to be created at the global level to satisfy the new scale of economic operations.3Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism (Blackwell: Oxford, 1983). This new culture helps establish and maintain the conditions under which a global division of labour operates and the moral and legal terms under which people participate in it. International relations, in short, are becoming more like what we understand as domestic political relations.

At least they would be if not for the fact that this burgeoning common stock of ideas and values is said to be producing antitheses in the form of counter-cultures or cultures of resistance. Old forms of class consciousness, new social forces based on identities or issues, and all sorts of revived ethnic, national and religious localisms may be understood in these terms. The attempt to do so, however, uncovers two problems. First, some elements of a burgeoning cosmopolitan world culture, those associated with the idea of an emerging global civil society, for example, like the idea of universal human rights, the need for codes of conduct for big corporations, or for restrictions on nuclear proliferation, may be also understood in terms of strategies of resistance to hegemonic projects. Secondly, while cultural responses to cosmopolitan or hegemonic conceptions of globalization may be themselves understood as global phenomena, very often this is not how their participants understand themselves. They accept neither the global characterization of what they are up against nor, indeed, the characterization of themselves in essentially reactive terms. Globalisms, in either their cosmopolitan or hegemonic forms, are seen as the projects of a particular culture from a particular part of the world, and that culture, in its turn, is seen as belonging to an outside contender or rival for primarily regional power and influence.

Instead of one “big” culture, cosmopolitan or hegemonic, provoking a series of cultural responses, therefore, we are presented with a world in which a number of “big” cultures are in contention with one another. These culture worlds are in contention not merely because they have different ideas regarding how their people should live, but because they incorporate views on how all people should live. Some of them, at least, have universal aspirations and this entails that none of them can leave each other alone. The most obvious protagonists in this regard are the market democracies of the “West” on the one hand, and the “world of Islam” stretching from Morocco on the Atlantic Ocean to Indonesia and the Philippines on the South China Sea on the other. The modernizing project of the former is presented as clashing with the efforts of the community of the faithful to rediscover or revive its own transnational religious and political way, if not forward exactly, then towards God and away from the material corruption of this world.

This view of clashing civilizations is problematic, not to say controversial. It may be objected that it does violence to the facts. In no simple sense does a “world of Islam” actually exist. The faith is divided into at least two confessions. The expression of both is underlain by strong local cultural differences and overlain by different degrees of accommodation with modernity. Similarly, the West is divided, and some would say increasingly so, between US and European models reflecting their respective cultural priorities. Identity problems such as these underlie the difficulty of seeing civilizations as actors in any meaningful sense. The West, for example, does not act. Other kinds of actors which may share aspects of its culture claim to act in its name. To objections based on appeals to the evidence may be added those which rest on moral or prudential grounds. We should not speak in terms of clashing civilizations, it is sometimes argued, because of the self-fulfilling potentials of such talk. It may exacerbate existing differences and create new ones where there were none before. This is not really an objection to the claim that the world can be divided along civilizational lines. Indeed, it may confirm the extent to which it can, for the stories we tell must have some correspondence with reality or resonance with the way in which others apprehend that reality if they are to secure an audience. “Big” culture stories clearly seem to resonate more than in the past, and the moral questions they pose do not revolve around whether or not they should be told, but how and with what ends in view.

There are, nevertheless, real difficulties with referring to, for example, African, Hindu or Confucian civilizations as actors or forces in the world, especially when, as in the case of the latter two, culture has an alternative and more obvious referent. It is India and China which act in the world as collective actors, not the civilizations of which they happen to be the principal bearers and vehicles. The fact that this is so reminds us that most people still regard states as the most important actors in international relations and, thus, the society of those states and its associated culture as the primary international culture. From this perspective, cosmopolitan claims on behalf of humanity as a whole, various hegemonic visions of how we all really want to live, other faith-based claims about how God wants us to live, and interest-based claims about what particular groups of people need if they are to fulfil their potential (or merely survive), are all mediated to a great extent by the voices of territorial, sovereign states in their relations with one another.

Few doubt that the state system remains the most important formal organizing principle of the international system, and most people believe that this formal organizing principle best captures how the world actually lives, if not must live or ought to live. They argue much more about the practical application of the states system, especially over who gets their own state and who does not, than they argue about whether or not the world should be carved up into states. The culture of the states system or society has its own distinctive priorities. States ought to co-operate with each other to secure wider and agreed-upon goods, but where this is not possible, their primary responsibility is to themselves and the people who inhabit them, and it is right that this is so. If this account of the formal organization of international relations is broadly accepted, however, the extent to which it is actually true and should be regarded as right are increasingly challenged by scholars, citizens and even governments alike.

We live, then, in an international world of at least three cultural levels: global/hegemonic; civilizational/regional and state/national, with many other transnational identities cutting across these levels. Several of these cultures purport to capture what life in general is and ought to be about. They do so in ways which theoretically call into question and practically undermine each other’s premises. How, one wonders, is it possible to conduct diplomacy, effectively representing these identities and their interests to one another, in such a world, and what sort of culture does diplomacy itself need if its practitioners are to be effective?

“Small” Cultures

This is a difficult question to answer. The difficulties may be illustrated by shifting our attention from the rise of “big” culture in international relations to what I call the “small” culture of the organizations in which we work. The rise of “big” culture has been mirrored by an increased interest in “small” culture which is, at first glance, paradoxical. It is so because the focus is upon organizations viewed in primarily instrumental terms and how to maximize their efficiency in these terms, what we might regard as post-cultural or even anti-cultural themes. Implicit in any social organization is the idea of how people might be best organized to achieve a wide range of goals. Even in a community of people who are not conscious of themselves in these terms – regarding themselves, for example, as simply existing as part of some sort of natural order – some thought must be given to how certain collective purposes, or individual purposes requiring collective effort, might be more easily achieved. From such reflections we may trace the eventual emergence of both a science of society which sees the latter in primarily functional and instrumental terms and an applied science which focuses on how societies might be best organized to perform functions and achieve purposes. This applied science has adopted the idea of culture and adapted it to help solve its own problems by asking, and posing answers to, the question, “what sort of general beliefs, values and senses of identity on the part of the members of an organization or society will best promote both desired goals and the social arrangements designed to secure them?”

Attempts to instrumentalize the idea of culture in this way pose two questions familiar to anyone who has participated in such exercises. Do they work and for whom? A common response to the first question is that they are a waste of time. In this view, they bear testimony only to the wealth and gullibility of organizations which commit time and money to the elevation of useful insights about self-awareness into rigid and time-consuming operational principles which hinder more than they help. A common response to the second is that the construction of such cultures is an exercise in soft power on behalf of particular agendas not necessarily consistent with the aims of an organization, its members or those on behalf of whom they work. Not only that, it may be regarded as a particularly intrusive exercise of soft power, a bid for the soul, perhaps, rather than for merely external compliance. Both answers contain elements of truth, although, insofar as all attempts to get people to do things must result in a number of failures and all attempts to get people to do what they otherwise would not have done must result in a number of complaints, these truths must be kept in perspective.

Behind such concerns, however, lie two more analytical questions. First, does the attempt to create, build or foster a small culture within an organization fundamentally misunderstand how cultures, or ideas of cultures, form and how they operate? Big cultures appear to have formed through processes more akin to sedimentation and evolution than construction and revolution. They look natural rather than synthesized. Thus, there looks to be something fundamentally different between the way “the world of Islam” has emerged and the way in which, for example, a government seeks to create a new culture in the staffs of its foreign service or universities, by which they are encouraged to think of themselves as value-adding, service providers with clients. This is not the case. It is hard to imagine even the most natural-looking of cultures developing without some element of conscious construction, and we can see conscious elements in the production and reproduction of real cultures today. Naturalization is probably more a consequence of the passage of time than culturalists would like to think. This should not prevent the generation of interesting hypotheses about, for example, the relationship between a culture’s ability to appear natural and its effectiveness at providing a frame and reference for how people think of themselves and what they do.

Insofar as all cultures involve synthetic elements, however, this leads to the second question. What are sources of these elements? I say sources, for it would seem unlikely that a culture has a single set of sources for its conscious and synthetic element. Indeed, in a world where the idea of “big” and contesting cultures is in ascendancy, it might be expected that a “small” culture like that of diplomacy would provide one of the terrains for those contests. Thus, while we may wish to know what kind of diplomatic culture would best facilitate the representation of big cultures and their agents to one another, we must acknowledge that actual diplomacy reflects the priorities of those agents and its culture bears the marks of theirs. The question is, “to what extent?” which is really a polite way of asking the questions which were posed at the beginning of the paper. Does an independent diplomatic culture in the sense of a common set of experiences, pool of memories, way of thinking, reasoning and communicating exist? If it does exist, does it matter?

Diplomatic Culture and Its Sources

The elements of such a culture are easily identified by considering how the members of a diplomatic corps or the diplomatic community at an international organization regard one another as “dear colleagues.” First, they will be aware of each other as servants of the national interest of their respective states as this is interpreted by their respective political leaders. Second, they will be aware of each other as members of complex organizations with their own sets of organizational and bureaucratic interests. Both are elements of what might be termed a culture of sympathy. Footballers and soldiers, for example, might share these sorts of elements of an outlook on life with people in other teams or armies and still primarily be opponents or enemies. The components of a diplomatic culture go beyond a sense of sympathy with colleagues who, nevertheless, remain on the other side of the boundary, to a sense of being involved with them on common projects or possibly a common grand project.

Thus, the third element is that of maintaining the conditions which make diplomatic work possible. An obvious example of this would be their commitment to the idea of diplomatic immunity and the sense that diplomats as a body are, for certain purposes, separate from the rest of humanity. A fourth element reflects the concern that the process of communication does not itself become a source of unwanted tension and conflict in a relationship. Hence arises the profession’s emphasis on both precision and courtesy in communication and on keeping the personal relations of diplomats and the political relations of those whom they represent separate. Fifth, we may identify a value placed on understanding not only what is happening on the other side of the hill, but also on why, in terms of the people who live there. And finally, a diplomatic culture would seem to incorporate a preference for the peaceful resolution of disputes. In short, when compared to the rest of us, diplomats are, indeed, the successors to the angels that their forebears claimed them to be.4G. R. Berridge, Diplomacy: Theory and Practice (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002). G. R. Berridge and Alan James, authors of A Dictionary of Diplomacy (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2003), provide contrasting views on whether diplomacy must be characterized by peaceful ends and peaceful processes).

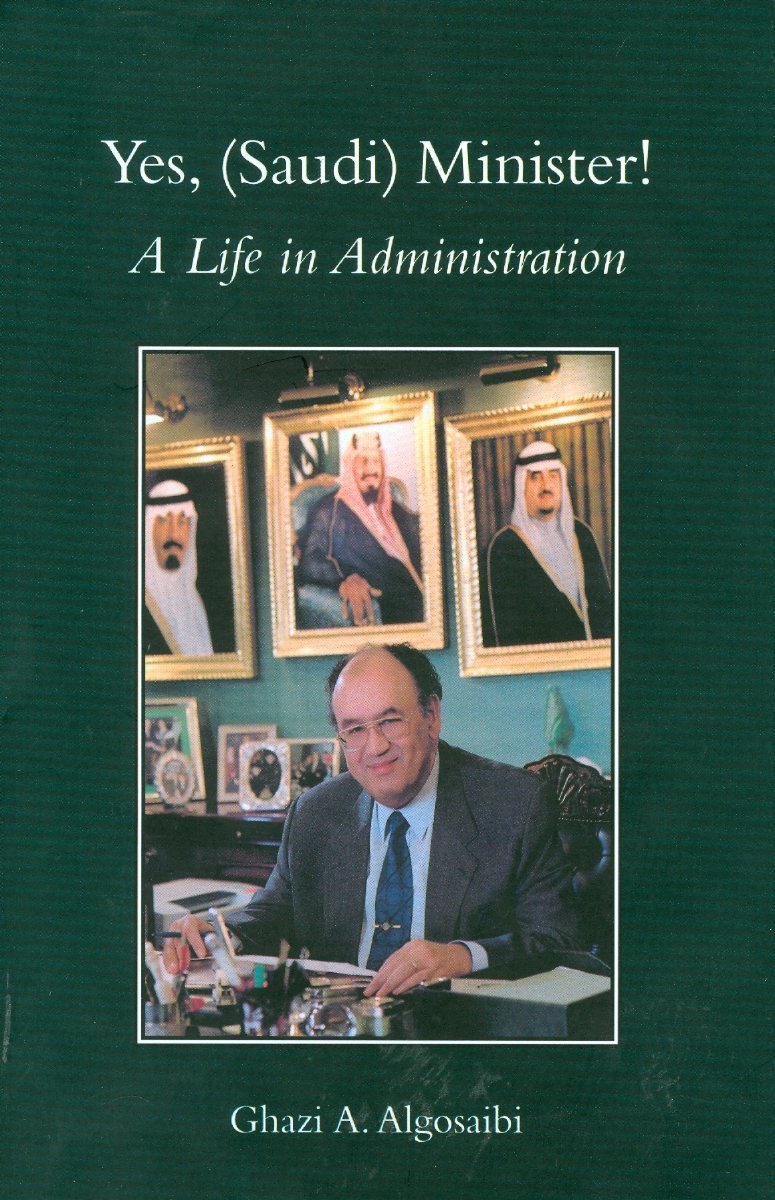

At least, they would be if they were able and willing to live up to the high standards embodied in the culture of their profession. The possibility exists that these elements of a diplomatic culture are no more than pieties that we all express on occasions without deep practical commitment. Indeed, arguments suggest not only that diplomats cannot live up to the high standards implied by the culture which presents them as heroic go-betweens, but also that this is itself one of the great obstacles to better international relations. Diplomats, it may be argued, cannot live up to the standards of their own culture because, in practice, they are far more formed by the culture of the domestic worlds in which they are rooted. Navari, for example, identifies a range of diplomatic cultures consistent with the requirements of dynastic, absolutist, republican and liberal democratic states respectively.5Cornelia Navari, unpublished paper presented at Birmingham University, June 2003).Each comes with its own distinctive conceptions of who or what is to be represented, what constitutes an interest, and what are appropriate means for securing such interests.

Arguably, we are witnessing a similar sort of shift today with the rise of trading states and virtual states. Their diplomats are told that they must acquire new management and entrepreneurial skills which will enable them to bring people and resources together for a variety of purposes in an environment where information is increasingly available to more people who will attempt to act on their own account. In short, diplomatic training is becoming more like the training that anyone else who works in big organizations – private companies, government ministries, colleges and hospitals, for example – undergoes as they are asked to think of themselves as providers of a service to a range of clients. Nothing is intrinsically wrong with this, and some aspects of it may be quite useful. The important question to ask, however, is whether these changes are of a magnitude which would make the activity of diplomacy in 16th century Europe, for example, unintelligible to a present-day ambassador or render an Athenian proxenoi incapable of understanding what is going on today. I suspect not, because there is a core to our respective professions and businesses that this sort of training and acculturation does not touch or, at worst, merely impedes.

It may be argued, however, that even this core, the idea of an independently existing diplomatic culture with its own sense of the world, is an emanation of something else. Diplomacy is conventionally presented as a response to a condition of human relations that exist separately from it. People live in separate political units and because these units have relations with one another, the need for diplomacy arises. Der Derian takes issue with this conventional understanding because, in his view, it obscures diplomacy’s role in reproducing and maintaining what he calls conditions of estrangement in human relations.6James Der Derian, On Diplomacy (Cambridge, MA: Oxford University Press, 1987). Every time diplomats attempt to reconcile national positions, whether it be on the future of a piece of territory, the size of fishing quotas, or limits on the production of carbon dioxide, the premise on which they operate helps to reproduce a world in which positions on such issues are both multiple and national. Diplomacy, in this view, not only manages the consequences of separateness, but, in so doing, it reproduces the conditions out of which those consequences arise. Presenting itself as an independent response to natural and permanent conditions, therefore, is simply diplomacy’s part of the process by which human beings are maintained in conditions of estrangement from one another.

Problems with this argument are associated with the concepts of estrangement and alienation which it uses. The argument assumes that neither estrangement nor alienation is the default setting for human beings in their relations with one another. Indeed, conditions of estrangement and a sense of alienation require a great deal of work to maintain. However, the ideas of estrangement and alienation also imply their corollaries, a process of making familiar, which is quite intelligible, and a true or natural condition from which a condition of alienation can exist which is far more problematic. We may imagine diplomats involved in making the strange seem more familiar by cultivating good relations, or even making the familiar seem more strange by creating the conditions for a war. It is less easy to imagine them involved in maintaining or constituting conditions of alienation, for that raises the question “alienation from what?” Unless some essentialist sense of natural or good human beings living in natural or right relations with one another is implied, it is hard to think what this might be. History provides us with powerful motives for wishing that such human beings were more than a theoretical possibility, but few reasons for thinking that they actually might be and some grounds for worrying about the practical consequences of thinking otherwise.

The Autonomous Component in Diplomatic Culture

If we can separate the notion of estrangement from that of alienation, however, we have the element of diplomatic culture that we might regard as autonomous and belonging to diplomats and the activity of diplomacy. This component may be regarded as an encounter culture, and its workings are best illustrated initially by employing the device often used by writers on diplomacy, namely, that of postulating its origins and early development. We imagine the prototypical heralds and messengers, products of their respective societies as they undoubtedly were, once they walked out of their home settlement or found their donkey in the trade caravan. They move on to the new terrain of someone else’s system of rules, conventions, power and authority, or the space between such systems. How should they talk to strangers and how should they talk to those employed by strangers in the same capacity as themselves? Can they borrow from the herders who inhabit border zones but for whom the borders have no significance? Can they borrow from the traders who have preceded them but for whom the questions with which they have now to deal did not arise? How do those who claim to be supreme gods or the descendants of such talk to one another?

In the case of the Amarna system we have a record, admittedly sparse, of diplomatic activity with which to supplement our efforts to imagine what diplomacy was like between the early empires. In one account of a dynastic marriage between Mittani and Egypt, for example, we see their respective ambassadors, Keliya and Mane, jointly reporting on the acceptability of the bride, the bride price and related gifts; travelling together; and being detained together when a hitch arises in the negotiations.7Pinhas Artzi, “The Diplomatic Service in Action: The Mittani File,” in Amarna Diplomacy: The Beginnings of International Relations, ed. Raymond Cohen and Raymond Westbrook (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2000), 205-211). We see each of them working to reassure both sovereigns at difficult moments, and it seems reasonable to infer that they collaborated in this effort. Doubtless the ambassadors’ personal prestige became linked to the success of the relationship, but this diminishes neither the distinctiveness of their shared position between two worlds nor their preoccupation with making relations between those two worlds work.

We have a far richer sense of similar sorts of encounters between strangers from the records of European expansion into the rest of the world. On multiple occasions it is possible to see the terms being worked out through which relations can be conducted with others, even when basic questions of whether they are human, like us, and, thus, possibly, equal to us, have not been worked out. The Iroquois, for example, found it difficult to establish the full relations of forest diplomacy with someone whom they could not regard as kin. Once they had decided they wanted relations with someone, therefore, the first task was to give them a name by which they might be adopted into their clan system. The Europeans, in contrast, assumed that diplomacy took place between those who regarded themselves as different from, but equal to, one another.8William N. Fenton, “Structure, Continuity and Change in the Process of Iroquois Treaty Making” in The History and Culture of Iroquois Diplomacy, ed. Francis Jennings, William N Fenton, Mary A. Druke, and David R. Miller (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse UP, 1985), 12. The point is not that these sorts of first principle differences had to be settled before relations could be conducted (often, they were never settled), but that relations had to be conducted by someone nevertheless, and in the midst of such differences.

Sometimes, these differences had fortunate synergies. In the Amarna system it was customary to marry out one’s princesses to lesser courts as demonstrations of standing, a practice which resulted in many arguments about the relative standings of the great kings. Egypt, in contrast, received princesses from courts it regarded as lesser as a mark of its superior standing. As a consequence, dynastic marriages with Egyptian princesses might be arranged without either party having to regard itself as subordinate. One imagines diplomats leading those who argued that this fundamental difference in dynastic marriage practices and understandings did not have to be resolved.9Samuel A. Meier, “Diplomacy and International Marriages,” in Amarna Diplomacy, 165-173.

More often, however, a way of living with differences unresolved had to be found, typically by recognizing what was important to the other side without understanding why. In the forest diplomacy of the Iroquois, for example, diplomatic démarches and treaties were made by “reading” them into wampum strings and belts with great ceremony and were received and maintained by having the strings and belts “speak” through a mediator. Great importance was attached to the renewal of agreements by frequent face-to-face exchanges of principals and/or their representatives who would, in the metaphors of forest diplomacy, “re-polish” the covenant chains which bound their peoples. The agreement was said to have no life without such a process of renewal. The Europeans, in contrast, committed their agreements to paper and, in so doing, expected them to remain in force until other agreements, similarly committed, superseded them. Europeans were perplexed by requests for meetings to renew agreements to which they already considered themselves bound by their signatures, while the Iroquois were surprised when the Europeans attempted to hold them to agreements which had not been renewed at regular intervals. These differences were never fully resolved, but what the diplomats of both sides quickly learned was to insist upon their counterparts’ observing the forms which they did not understand but knew to be important. If a negotiated agreement was to be regarded as serious, then the Iroquois insisted that the Europeans sign bits of paper to which they affixed their own signs, while the Europeans insisted on being presented with wampum.10Mary A. Druck, “Iroquois Treaties: Common Forms, Varying Interpretations” in Iroquois Diplomacy, 89).

What we see then are men and women in the middle seeking not to reconcile differences between those they represented nor even to establish a common basis of understanding between them, but a way of conducting relations between peoples who maintain their own understandings intact. In this space between cultures, therefore, we see diplomats, bearers of their respective home cultures, developing their own culture with its own preoccupation. How do we find a way to talk to each other, possibly, but not necessarily, in such a way as to render our respective peoples less strange to one another? It may be objected, however, that this autonomous element of diplomatic culture, if it indeed exists, pertains only to the first contacts and early encounters of peoples who previously had nothing to do with one another. As the space between fills with various interactions creating their own communities of understanding, then surely both the distinctiveness of the diplomatic culture and the need for it would lessen. Indeed, it is frequently argued that diplomacy and its attendant culture are being left behind as levels of transnational interaction in other sectors rise and develop their own cultures. Diplomacy, it is said, serves only its original master, the state, in a world of many new international actors. Not only that, because of its culture’s outdated conception of the state, it serves it poorly. Worse, insofar as it works at all, it does so to keep people apart in spite of their similarities, rather than bringing them together despite their differences. Who needs diplomats, indeed?11Shaun Riordan, The New Diplomacy (Cambridge: Polity, 2002)

Seeing diplomacy as based on a vestigial and minimalist encounter culture from earlier times is, however, mistaken. For one thing, it is based on a misreading of the history of diplomacy. The latter, in fact, provides corroborating evidence for Buzan’s and Little’s claim that political-military systems of relations have typically followed the development of economic, social and religious relations between peoples.12Barry Buzan and Richard Little, International Systems and World History: Remaking the Study of International Relations (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) The ambassadors of Amarna travelled along trade caravan routes which were already established, as did the representatives of European powers who made contact with the Iroquois confederacy and the tribes beyond. The European legations to the Sublime Porte emerged from trading companies that were already in situ, and the system of resident embassies first emerged precisely because of the density and continuous character of relations between the states of northern Italy. In short, wherever diplomacy appears, encounters have already taken place and established patterns of relations. In what sense, therefore, can diplomacy be regarded as resting on an encounter culture?

One possibility would be to push its origins further back to when traders, worshippers, explorers and wanderers with a sense of themselves and others first encounter one another. In this view, the diplomats of the ancient empires, the classical city-states and European imperial powers merely adapted and formalized an encounter culture which had been developed in its essentials by those who had gone before them. This is possible, but it still does not explain why a culture based on problems associated with seminal encounters persists once relations are established and in the teeth of developments which one might expect to quickly supersede it. An alternative and better approach is to cease seeing encounters in primarily historic terms, that is, as defining moments which occurred at various points in the past between people who then, if they are allowed, proceed to become increasingly familiar with, and less strange to, one another.

Instead, we may think of encounters occurring and re-occurring between peoples who may know aspects of each other quite well and may have done so for a long time. They re-occur because of the kind of relationship which exists between these peoples, a relationship in which, for some reason, a sense of difference and separateness from one another is emphasized. Contact and continuous relations do not bring them closer together, at least not willingly. This sense of difference and separateness is not absolute, but a matter of degree. It is not, for example, entirely absent from the relationship between lovers nor does it completely dominate the relations of groups in an ethnic conflict. However, insofar as a sense of difference and separateness exists between peoples who conduct relations with one another, those relations will have a diplomatic character, and those responsible for conducting them will experience the predicaments and imperatives which have given rise to a diplomatic culture.

If this is the case, then the autonomous element of diplomatic culture neither estranges nor makes familiar necessarily. Neither the “confidence curve” nor diplomats’ commitment to it are unidirectional.13Eduardo Gelbstein and Stefano Baldi, “Jargon, Protocols and Uniforms: Barriers to Inter-Professional Communication,” paper presented at DiploFoundation conference on Organisational and Professional Cultures and Diplomacy, Malta, February, 2004, also available in this volume) Countries and peoples may be brought closer together or pushed further apart by the exercise of diplomacy. It reflects policy which, in turn, reflects broader economic, technological and, indeed, cultural trends, although these do not push in any single direction. Thus, it is perfectly possible for individual diplomats, from a European Union (EU) member state for example, to be engaged in activity which simultaneously renders the EU more familiar to the people of their member state while estranging the Union to outsiders. The specific separate aggregates and groupings in which people live may shift over time, as may the conditions which favour or hinder the ability of specific groups or types of groups to live separately and feel distinct. As the emergence of the international relations of “big” culture would seem to suggest, however, the separation principle remains a constant. When people feel or define themselves as such in their relations with one another, those responsible for conducting their relations will find themselves in the thin atmosphere of the encounter with little more than the autonomous element of diplomatic culture to help them.

Conclusions: Strengthening the Autonomous Component of Diplomatic Culture

Whether an autonomous component of diplomatic culture will come to the aid of diplomats, however, is another matter. The autonomous component of diplomatic culture operates as a weak force when compared to the far stronger national and statist component in which individual diplomats grow and mature, the priorities of which they are committed to serve. Its sources are fewer and more diffuse. We may suppose that some people are attracted to the profession by reasons that go beyond simply entering into the service of their country in a career which remains associated with personal status and prestige. Individuals of a more romantic cast may have made themselves familiar with the idea of diplomacy as a potentially heroic or tragic drama played out on the highest stage in human affairs. One suspects not many, however. Acculturation of this sort is more likely to come with experience or it will, at least, if there is time for reflection. Experience may wear down the hopes and aspirations with which people enter the profession. However, it will also enforce the sense that they, along with their colleagues in other services, constitute a community with a common set of predicaments and priorities, which, to a greater extent than is the case with other professions, are bound up with the international world they represent and help to keep running. Lawyers, professors and footballers may also acquire this sense of common professional identity and interests, but the worlds in which they operate are sustained by many other things. Not so the world of diplomacy; for diplomats, to an extent greater than lawyers, professors and footballers, not only serve their professional universe, they constitute it.

Can diplomats be acculturated to this sense of themselves only by experience? The latter may, indeed, be the best teacher, but diplomatic educators have a great stake in believing that experience is not only an inefficient and uneven teacher, but also that it can be helped. People can be prepared at the onset of their careers to absorb and make the most of the lessons of their experiences to come. The implications of my argument that an autonomous component of diplomatic culture exists are, therefore, considerable for how we ought to undertake diplomatic training and education. The focus of the latter in recent years has been on two priorities. The first has been technical skills, drafting communications and agreements, for example, and doing so in an era when information technologies are constantly being transformed with uncertain consequences for the way in which diplomacy is conducted. The second focus has been on imparting insights from intellectual disciplines like economics, psychology, and the management sciences. New subjects, for example, environmental sciences, have been tacked on to the curriculum when the need for them has become apparent. Diplomacy, per se, has been relegated, sometimes by default and sometimes by intention, to the preambles and afterwords of programmes designed thus.

What is needed is for diplomacy, the science and arts of managing relations between those who regard themselves as separate and different, to be placed back at the centre of such programmes. In theory, this would involve treating what I have identified as the autonomous component of diplomatic culture as diplomacy’s own culture. In practice, it would involve getting diplomats to think of themselves as members of their respective services less and as members of an international profession more. In this regard, the diplomatic corps is an institution to which both academic and professional attention may be long overdue.

Putting diplomacy back at the heart of diplomatic education and training will be difficult for two reasons. First, developments in diplomatic education and training in recent years reflect both the priorities of those who generally pay the educators and the more widespread sense that diplomacy of the sort I am talking about is primarily a historical phenomenon which yields a few insights and many more banana skins. Teaching diplomacy, therefore, would have to take on something of the character of a subversive activity. Indeed, it would be doubly subversive. It would depart from what those who control the purse strings want taught, and it would contribute to making their respective visions of the world in which we will all be happy harder to achieve (which is no more than saying that, as always, diplomacy has a role to play in saving governments and others from their own worst selves).

To be subversive in both ways will require the application of considerable intelligence and tact, not to mention ketman, on the part of the diplomatic educators. I have no doubt that they are up to it and, indeed, that a measure of this sort of thing is going on already. However, teaching diplomacy as a subversive activity is inhibited by the second difficulty, namely that serving diplomats who have the experience have not been the best communicators of what their experience holds and has to teach. Historically, diplomacy has been an elite business with a sense of recruiting the best, those capable of grasping the essentials without being told or, at least, learning them quickly from a few hints, nods and winks. Anyone who needed more did not belong, and experienced diplomats have long been unable or unwilling to spell out the elements of their craft to those who cannot grasp them for themselves. We all now know a great deal more about what is and, more often, what is not going on in nuanced communication societies. The deep understanding which appears to hold them together may be no more than a mixture of bluff, mystery and misunderstanding bound by pressures for social conformity. Even so, such a system served when foreign services could rely on recruiting the brightest, the best, and the most conforming to a gentlemen’s game for which the players were unambiguous and the rules relatively simple. It has not served so well when the fundamental assumptions around which the diplomatic culture has been organized can be, and have been, challenged at all levels of societies.

Under such conditions, experienced diplomats have been ineffective at reflecting on what they do in ways which satisfy anyone other than their own constituency of enthusiasts or those who want to hear vignettes of working with the great and good. Habits of discretion and humility, sheer busyness and, perhaps, a sense that no one is interested have inhibited the reflections of diplomats on their own craft from being more than implied or notes in the margins. The result is, however, that diplomats often appear puzzled by what professors, politicians and other voices of the chattering classes (including, sometimes, their own political masters) are saying is happening to international relations. They have been particularly ineffective, for example, in addressing the debates about who is now entitled to and who now needs representation.

Consider the response of embassies to arguments about the rise of public diplomacy. They may ignore them, which, to judge by the failure of most embassies to engage in public diplomacy of any sort, most of them do. They may address the arguments in such a way as to suggest that “they just don’t get it.” Public diplomacy, for example, is simply seen as providing a series of new conduits in the receiving state along which the embassy must get out “our line.” Or they may flirt with coalition-building and issue-promoting activities which undermine the established rationales for resident embassies and restrictions upon them without realizing that this is what they are doing. One gets very little sense of an engagement from a diplomatic perspective with the arguments and assumptions which fuel the trends towards more public diplomacy or more outsourcing of diplomatic activities, or more involvement by private citizens talking directly to one another. Therefore, the first step in bringing diplomatic culture back into the heart of training and educating in diplomacy may involve bringing senior and experienced diplomats back to school. In the first instance, however, they will be asked not to impart, but reflect on the assumptions of their own culture and how to make these assumptions more explicit and intelligible to others. Only then, perhaps, can the potentially subversive activity of teaching diplomacy, as opposed to teaching other things to diplomats, proceed apace.