Author: R.S. Zaharna

Asymmetry of cultural styles and the unintended consequences of crisis public diplomacy

2004

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in America on 9/11, Americans asked themselves, “Why do they hate us?” The attacks underscored the importance of public diplomacy. As American Congressman Henry Hyde noted during one of the congressional hearings, “the perceptions of foreign publics have domestic consequences.” American President George Bush echoed the sense of urgency when he said: “We have to do a better job of telling our story.”

In short order, a flurry of activity started with the aim of getting America’s message out to the world. The US State Department put a veteran advertising executive in charge of America’s public diplomacy initiative. Both the Senate and House held hearings, passing the new “Freedom Promotion Act of 2002,” which injected $497 million annually into the budget of public diplomacy. First the Pentagon, then the White House, established special offices to help with America’s public diplomacy initiative.

With such a concerted effort at the highest levels of the American government to win the hearts and minds of foreign publics, officials expected increased international understanding and support. Instead, the opposite happened. America’s intensified public diplomacy initiative resulted in decreased support for American policies.1Several studies, including those conducted by the Pew Research Centre, the German Marshall Fund, the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations and the University of Michigan, cite a precipitous drop in favorable support for the United States around the globe, among traditional American allies as well as new adversaries. The Economist (2 January 2003) has written of similar findings in a report “Dealing with a Superpower,” as has the Council on Foreign Relations, Public Diplomacy: A Strategy for Reform (2 August 2002), available online (http://www.cfr.org/pubs/Task-force_final2-19.pdf). Much has been made of the rift between the US and its major European allies, yet American support declined in Asian, African and Latin American countries as well. In the Arab world, where the US conducted the most intensive public diplomacy, anti-American sentiment grew rapidly.

The immediate explanation for declining support was the Bush administration’s war on terrorism and the American-led war in Iraq. However, the primary purpose of public diplomacy is to garner support from foreign publics for political policies. To be effective, public diplomacy must work not only in times of peace, but also in times of conflict. In fact, during times of conflict, garnering foreign support is even more imperative.

The critical question is: How did America’s efforts to intensify its public diplomacy result in a decrease of foreign public support for America?

Answering this question is particularly relevant to diplomacy and intercultural communication. Public diplomacy appears to entail more than translating official messages and giving them the widest possible dissemination to a foreign audience. While translation may overcome the language barrier, it may not overcome the cultural barrier. Just as culture shapes the communication of a people, it appears that culture shapes the public diplomacy of a nation.

Many of the American public diplomacy initiatives reflect a uniquely American cultural style of communication, public relations and advertising. Although the American style resonated positively with the American public, it resonated negatively with foreign publics. This difference in perception would not be a problem if it were possible to segment audiences. However, today’s global media and technology have made public diplomacy an open communication forum; one can no longer segment the domestic public from foreign publics.

Thus, in addition to crossing the language hurdle, it appears equally critical that effective public diplomacy bridge different cultural styles so that a nation’s public diplomacy positively resonates with foreign publics as well as with one’s domestic public. If a nation does not address the asymmetry of cultural styles, its public diplomacy efforts may inadvertently magnify differences between the domestic and foreign publics and amplify international tensions.

This appears to be what happened with recent American public diplomacy. The more America intensified its efforts – relying exclusively on American-style public diplomacy – the wider the gap became between the domestic and foreign publics. Instead of increased understanding and support, there was increased misunderstanding and tension. Instead of achieving greater international unity, divisions grew and America became increasingly isolated within the international community. None of this was intended. This opposite result, based on asymmetry of cultural styles of public diplomacy, is the unintended consequence of crisis public diplomacy.

The purpose of this paper is to explore this issue. The first section contrasts the American cultural communication style with other styles. The second section identifies the cultural features of an American style of public diplomacy that resonate positively with the American public, yet negatively with foreign publics. The concluding section explores how an asymmetry of cultural styles can produce the unintended consequences of crisis public diplomacy.

The American Style of Communication

Scholars have distinguished cultures in several ways. This section briefly highlights some of the salient features of the American cultural style of communication.2For more complete discussions of American cultural patterns, see Edward C. Stewart and Milton J. Bennett, American Cultural Patterns: A Cross-Cultural Perspective (Yarmouth, Maine: Intercultural Press, 1991); and John C. Condon and Fathi Yousef, An Introduction to Intercultural Communication (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1983). Although America is rapidly becoming a more multicultural society, the cultural features mentioned here characterise communication patterns still prominent in the American media and society.

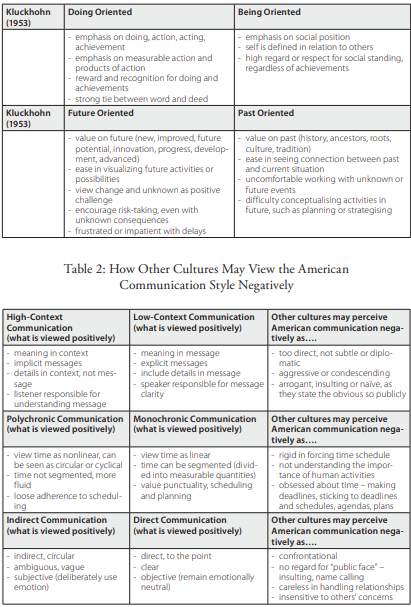

Low-Context and High-Context Cultures

Anthropologist Edward T. Hall, sometimes referred to as the “father of intercultural communication,” characterised American culture as “low-context.”(Edward T. Hall, Beyond Culture (New York: Anchor, 1976).) He distinguished low and high context cultures by the amount of meaning imbedded in the code versus the context. Low-context cultures tend to place more meaning in the language use or message itself and very little meaning in the context. For this reason, communication tends to be specific, explicit, and analytical.(Stella Ting-Toomey, “Toward a Theory of Conflict and Culture,” in Communication, Culture and Organisational Processes, ed. L. Gudykunst, L. Stewart and S. Ting-Toomey (Beverly Hills: Sage, 1985).) Chen and Starosta pointed out that low-context cultures tend to use a direct verbal-expression style; people tend to directly express their opinions and intend to persuade others to accept their viewpoints.3G. Chen and W. Starosta, Foundations of Intercultural Communication (Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1998), 50. In analysing messages, low-context cultures tend to focus on what was said in the words and phrasing.

In contrast, cultures found throughout Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Arab world have a more high-context communication style. In speaking of high-context cultures, Hall states, “most of the information is either in the physical context or internalised in the person, while very little is in the coded, explicit, transmitted part of the message.”4Edward T. Hall, “Context and Meaning,” in Intercultural Communication: A Reader, ed. Larry Samovar and Richard E. Porter (Belmont, California: Wadsworth, 1982), 18.For high-context cultures, what was said cannot be understood by the words alone; one has to look at who said it, when they said it, where they said it, how they said it, the circumstances in which they said it, and to whom they said it. Each variable helps define the overall meaning of the communication event. Thus, in high-context exchanges, much of the “burden of meaning” appears to fall on the listener. In low-context cultures, the burden of meaning falls on the speaker to convey accurately and thoroughly through the message.

Monochronic and Polychronic Cultures

Hall also spoke of the American culture as monochronic in terms of its view and use of the concept of time. As the term suggests, monochronic cultures focus on one thing at a time. In this regard, Americans tend to view time as linear (“spread out across time,” “the time line” or “time frame”). Being punctual, scheduling and planning tasks to match time frames are valued behaviours. Americans view time as a commodity (“time is money”) that can be bought (“buying time”), spent (“spending time”) or wasted (“wasting time”). Although time is technically an abstract phenomenon, in the monochronic view it becomes a concrete reality. One of the most outstanding features of a monochronic culture is that because time is so concrete and segmented, people prefer to do “one thing at a time.” Monochronic cultures view trying to do too many things at one time as chaotic.

Polychronic cultures have a non-linear view of time as circular or cyclical in nature (“what goes around, comes around,” “life is a circle”). Thus, what passes can reoccur later. Punctuality and scheduling occur, but rarely with the ardent fervour found in monochronic cultures. Schedules are not “etched in stone” but, rather, are loose as a matter of cultural habit instead of personal habit. People from polychronic cultures, as the prefix “poly-” suggests, find little difficulty doing many things at one time and often will meet with several different people – each with different agendas – at the same time. Because time is not linear or segmented, matching specific activities with specific time frames is not necessary. Times and activities are fluid.

Direct and Indirect Communication

David Levine spoke of the American cultural preference for direct communication.(David Levine, The Flight from Ambiguity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982).) “Direct communication works to strip language of its expressive overtones and suggestive allusions,” Levine said. “It aims for the precise representation of fact, technique, or expectation.”(Ibid., 32.) The direct style of Americans is evident in many common expressions such as “Say what you mean,” “Don’t beat around the bush,” and “Get to the point.”5Ibid., 29. The direct verbal communication style strives for emotional neutrality or objectivity. Openness and clarity are valued.

The indirect style of other cultures deliberately uses affect and ambiguity to create subtle nuances among messages and meaning. As Levine noted, indirect communication “can provide a superb means for conveying affect. By alluding to shared experiences and sentiments, verbal associations can express and evoke a wealth of affective responses.”6Ibid., 32. In cultures where “saving face” is important, one’s skill is not in how directly one can state criticism, but rather in how cleverly one can disguise it.

Linear and Non-linear Thought Patterns

Anthropologist Dorothy Lee spoke of how different cultures support different thought patterns: linear and non-linear.(Dorothy Lee, “Lineal and Nonlineal Codification of Reality,” in The Production of Reality, ed. P. Kollock and J. O’Brien (Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine-Forge Press, 1977), 101-111. (Reprinted from Psychosomatic Medicine, 12 (1950), 89-97).) Carley Dodd characterised American culture as having a linear thought pattern.(Carley Dodd, Dynamics of Intercultural Communication (Dubuque, IA: Wm. C. Brown, 1982).) As members of a linear culture, Americans tend to stress beginnings and ends of events, to prefer unitary themes, and to rely heavily on empirical evidence. They tend to present points sequentially and to follow an underlying organisational structure. For example, this article, with its introduction, body and conclusion, is very much in keeping with the linear progression of ideas. The use of subheadings further illustrates the practice of segmenting the whole into parts and then reconnecting them sequentially, following what is culturally defined as a “logical order.”

Non-linear cultures, says Dodd, are characterised by the “simultaneous bombardment and processing of a variety of stimuli so that people think in images, not just words.”7Ibid., 162. The non-linear thought framework typically has multiple themes, is expressed in oral terms and heightened by nonverbal communication. The visual/aural medium of television, with its simultaneous bombardment of the viewer with multiple messages, is analogous to communication in non-linear cultures, whereas the linear pattern of written texts is more representative of linear cultures. People comfortable with the non-linear style move easily between ambiguity and fluid metaphors to create meaningful associations. For them, to separate the parts from the whole is to lose the meaning and emotional resonance of the communication experience. From the linear perspective, the idea of multiple themes without an ordered pattern or underlying structure is perceived as illogical or disorganised.

Literate and Oral/Aural Cultures

The American culture also reflects many features common to print or literate cultures as opposed to oral/aural cultures. Literate dominant cultures tend to place a higher premium on accuracy and precision in a message than on symbolism and emotional resonance.(W. Ong, “Literacy and Orality in Our Times,” Journal of Communication, 30 (1980), 197-204.) The focus on accuracy may relate to the historical purpose of the written word – to record, preserve, and transmit information over time and space. Literate societies also favour evidence, reasoning and analysis over what their members view as a less rational, more intuitive approach. This contrasts with the logic of oral cultures, where a single anecdote can constitute adequate evidence for a conclusion and a specific person or act can embody the beliefs and ideals of the entire community.(E. Gold, “Ronald Reagan and the Oral Tradition,” Central States Speech Journal, 39 (1988).)

In oral cultures, a greater interplay occurs between the audience, speaker and message. In the tradition of Cicero, the speech should be “agreeable to the ear.”(Cicero cited in ibid, 160.) Aural ornaments such as formulas, humour, exaggeration, parallelism, phonological elaboration, special vocabulary, puns, metaphor and hedges are critical.(See ibid and C. Feldman, “Oral Metalanguage,” in Literacy and Orality, ed. D. Olson and N. Torrance (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991).) Style overrides substance; an oral message may be valued more for its affective power to link an audience than for its cognitive merits. Such lapse in substance, however, is rarely a problem because the audience actively participates with the speaker to construct the meaning. Speakers strive for an emotional and participatory response from their audience.(Deborah Tannen, Spoken and Written Language: Exploring Orality and Literacy (Norwood, NJ: ABLEX, 1982).) The audience, in turn, helps fill in the meaning. As Henle noted, auditors will “go to considerable lengths to make sense of an oral message.”(M. M. Henle, “On the Relations between Logic and Thinking,” Psychological Review, 69 (1962), 371.) Similarly, Gold states, “the audience cooperates with the speaker by trying to understand the meaning or ‘gist’ rather than the actual content.”8Gold, “Ronald Reagan,” 170.

Individualist and Collectivist Cultures

Triandis, Brislin and Hui discussed the differences between collectivist and individualist cultures, characterising the American culture as individualist.9Triandis, Richard Brislin, and C. Hui, “Cross-Cultural Training across the Individualism-Collectivism Divide,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 12 (1988), 269-289. Individualist cultures value the goals of the individual over group or collective goals. In individualist cultures, a person tends to look primarily after his own interests or that of his immediate nuclear family. Personal accomplishments are important and individuals will take advantage of opportunities for advancement even if it means sacrificing personal relations. Group cohesion, without expressed consent, is often negatively interpreted as group pressure that impinges on the individual freedom. As Triandis et al. noted, individualist cultures tend to prefer horizontal (peer) relationships to vertical (superior-subordinate) relationships. Also, relationships tend to be utilitarian-based; individuals must perceive some benefit to “joining” or gaining “membership” to a group. Because such utilitarian relationships tend to be short-term or transitory, they are often explicitly defined via public statements or written contracts.

Collectivist cultures tend to value goals of the collective over goals of the individual. Triandis et al. observed that people from collectivist cultures “pay primary attention to the needs of their group and will sacrifice opportunities for personal gain.”10Ibid., 273. Distinctions between “in-groups” and “out-groups” are clearly defined and play a dominant role. Because the in-group protects the individual, the in-group receives the individual’s loyalty while out-groups tend to be regarded with suspicion. Relationships tend to be long-term, based on trust or historical context, and often implicitly acknowledged by both parties. While collectivists strongly encourage cooperation within the in-group, they tend to be “poor joiners” of new groups. Similarly, people from collectivist cultures tend to be more comfortable with power differences and vertical relationships.

Doing versus Being Cultures

Anthropologist Florence Kluckhohn described another dominant cultural divide with her distinction between activity-orientated and being-oriented cultures.(Florence Kluckhohn, “Dominant and Variant Value Orientations,” in Personality in Nature, Society, and Culture, ed. Clyde Kluckhohn and Henry A. Murray (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1953), 349-351; F. Kluckhohn and R. Strodtbeck, Variations in Value Orientations (Evanston, IL: Row Peterson, 1961).) An activity orientation places a premium on “measurable accomplishments through action.”(F. Kluckhohn, “Dominant and Variant Value Orientations,” 351.) Edward Stewart refers to the activity orientation as “doing” and categorises the American culture as a doing culture, with its emphasis on the importance of achievement, visible accomplishments and measurements of achievement.11Edward Stewart, American Cultural Patterns, (Chicago: Intercultural Press, 1972), 36. Such common American expressions as “How are you doing?” or “What’s happening?” express the American proclivity towards “doing.”

In contrast to “doing” cultures are the “being” cultures. Okabe observed that the American emphasis on achievement and development are not as important in a traditional vertical society (a “being” culture) where an individual’s birth, family background, age and rank are much more important. As he stated, for an individual of the “being” culture, “what he is” carries greater significance than “what he does.”12Roichi Okabe, “Cultural Assumptions of East and West: Japan and the U.S.,” in Intercultural Communication Theory, ed. W. Gudykunst (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1983), 24.

Future-Oriented versus Past-Oriented Cultures

Kluckhohn also distinguished between future-oriented and past-oriented cultures as a value orientation related to time.13F. Kluckhohn and R. Strodtbeck, Variations in Value Orientations. Future-oriented cultures, such as the American culture, tend to place a premium on change and innovation. New is good, and the promise of the future is better and brighter. One looks “ahead.” Looking “backward” carries a negative connotation similar to “being stuck in the past.” History serves as a “reference point” of departure for those moving forward. Often future-oriented Americans tend to become frustrated with historical detail, impatiently dismissing it as “irrelevant” or time consuming. They tend to engage more easily in such future-oriented activities as forecasting, scheduling, planning and strategising. The future tense of the verb “will” is used generously, if not forcefully, in American communication: “I will …” is often a signal of defiant personal resolve to overcome the past and meet future challenges.

In contrast, past-orientated cultures view with reverence the historical continuity of human existence. The past informs the present to such a degree that it is difficult to understand the present apart from the past. The historical context of any action is critical and thus discussion tends to draw on the past for meaning. Any comprehensive, “meaningful” understanding of a situation demands that it be viewed across the entirety of its existence. The future can also carry religious significance that bars its liberal use. For many Muslims, knowledge of future events is not the prerogative of mankind, but of God. Thus, whereas the future-oriented American speaker may use “I will” to stress personal resolve, the Muslim audience may view it as arrogant if not naive.

In summary, the American culture has numerous features and characteristics that dramatically contrast with those of other cultures. Many of the contrasting cultural perspectives presented here are typical of cultures throughout Asia, Latin America, Africa and the Arab world.

The American Style of Public Diplomacy

The American style of public diplomacy reflects the dominant American cultural style of communication. This is hardly surprising, given that communication is a pivotal feature inherent in public diplomacy activities. If one looks at American definitions of public diplomacy, communication is central.

According to the US State Department, “Public diplomacy seeks to promote the national interest of the United States through understanding, informing, and influencing foreign audiences.”(Planning Group for Integration of USIA into the Department of State, June 20, 1997.) American Ambassador Pamela Smith’s characterisation of public diplomacy reflects the earlier US Information Service definition of public diplomacy, namely, “to understand, inform, and influence foreign publics in promotion of the national interest and to broaden the dialogue between Americans and U.S. institutions and their counterparts abroad.”(Pamela Smith, “Public Diplomacy,” International Conference on Modern Diplomacy, Malta, February 15-18, 1998. Available online: http://conf.diplomacy.edu/conf/modern_diplomacy/papers/pamela_smith.htm.) Again, “dialogue” implies communication. Hans Tuch defined public diplomacy as “Official government efforts to shape the communications environment overseas in which American foreign policy is played out.”14Hans N. Tuch, Communicating with the World (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990).

Ambassador Smith listed the primary activities of public diplomacy: “to explain and advocate U.S. policies in terms that are credible and meaningful in foreign cultures; provide information about the U.S., its people, values, and institutions; build lasting relationships and mutual understanding through the exchange of people and ideas; and advise U.S. decision-makers on foreign attitudes and their implications for U.S. policies.”(Smith, “Public Diplomacy,” 1.) In the State Department’s Dictionary of International Relations Terms, public diplomacy’s “chief instruments are publications, motion pictures, cultural exchanges, radio and television”(US Department of State, Dictionary of International Relations Terms, 1987, 85.) – all are communication channels or media. Professor Glen Fisher, writing in 1979, was perhaps the most succinct in stating the link: “public diplomacy, which is, of course, a communications process.”15Glen Fisher, American Communication in a Global Society (Norwood, NJ: ABLEX, 1979), 124.

Given this link between communication and public diplomacy, it is not surprising that when the crisis of September 11th hit America, the State Department appointed a communication professional, Charlotte Beers, to head America’s public diplomacy efforts. Beers, a veteran advertising executive with more than forty years of experience, employed many of the communication tools of the trade. This included American style marketing, advertising, focus group research and even attempts at branding America’s image.

Putting a communication professional in charge of American public diplomacy was the first step in what appears to be the development of a uniquely American style of public diplomacy. Features of this American style are reflected in the goals, strategic approach and message appeals of American public diplomacy.

First, the goal of American public diplomacy focused on disseminating America’s message. If one looks at the broad strategic goals stated by Beers,16Charlotte Beers, “U.S. Public Diplomacy in the Arab and Muslim Worlds,” Remarks at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Washington, DC, May 7, 2002. Available online: http://www.state.gov/r/us/10424.htm. all focus on information transfer:

- The first is to inform our many publics of the content of U.S. policy – accurately, clearly and swiftly;

- Next, re-present the values and beliefs of the people of America, which inform our policies and practices;

- Third, define and provide dimension to the role that democracy plays in engendering prosperity, stability, and opportunity; and

- Fourth, communicate our concern for and support of education for the younger generations.

This information-centred goal is characteristic of the “transmission view” of communication as a linear mechanistic model that focuses on the sending, giving or imparting of information. While this model reflects many of the cultural features outlined in the American cultural profile presented in the previous section, this perspective is not shared by other cultures. James Carey contrasted the “transmission” with the “ritual” view of communication.17For full discussion, see James Carey, Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society (New York: Routledge, 1988). The ritual view of communication is more relationship-centred. Rather than focusing on a one-way transmission of information, cultures that use a ritual style of communication focus on two-way relationship-building strategies to create links between people. The difference is critical. Whereas the American style of information transfer resonated positively with the American public and was effective in rallying support from the American public, with other publics the transfer of impersonal information fell flat, or failed to resonate. For these cultures, without a relational base for interpreting the information, the information is meaningless.

Second, the strategy of American public diplomacy in communicating America’s message internationally with foreign publics reflected the same approach Americans use domestically with the American public. With the primary goal of information transfer, American communication campaigns tend to rely on mass media channels and advanced technology to reach the most people in the least amount of time. Noteworthy, in Beer’s statement, is the stress on conveying the information “accurately, clearly and swiftly.” This American emphasis on communication efficiency is reflected in the American use of mass media channels versus interpersonal channels of communication. For example, the telephone is faster than meeting face-to-face, thus it is used frequently. Much was made of President Bush’s “telephone diplomacy” in trying to rally foreign support for the UN resolutions. Similarly, Americans use intensive media blitzes – in which many officials say the same thing through numerous media outlets – to reinforce their message. The Sunday morning news interviews with high-ranking administration officials echoed America’s message domestically and stimulated American domestic support; however, it is unclear whether these interviews resonated with foreign publics.

In other cultures, interpersonal communication is a more effective means for reaching people. The “personal touch” is more important than speed. Additionally, not all audiences share the American public’s familiarity and trust of the mass media in disseminating messages. If one looks at the history of American public relations and marketing, America’s growth as a nation parallels advancements in the mass media and media strategies.18For discussion of factors that create an American style of public relations, see R. S. Zaharna, “An In-Awareness Approach to International Public Relations,” Public Relations Review, 27 (2001), 135-148. For example, mass-marketing techniques arose during the American industrial revolution to create a mass consumer base for the sudden increase in product supply. Not all countries use the mass media to link and create their nation as America does. Similarly, not all nations are as trusting of or dependent on the mass media as Americans for obtaining credible information. Whereas relying on the mass media is an efficient and effective medium for communicating with the American public, it may be less so for foreign publics. In fact, in cultures where interpersonal channels are preferred or where the mass media is not credible, the American public diplomacy strategy may have been ineffective, if not counterproductive, in communicating with foreign publics.

Third, the content and style of American public diplomacy messages also reflected the American cultural pattern. The American focus on message is characteristic of low-context cultures; it is the message itself that contains the meaning, not the context or audience. American officials focused on sending their message, as Undersecretary Beers stated, “accurately, clearly.” However, by not accounting for context, American officials were not able to control how foreign publics interpreted the message. For example, American officials were perplexed and alarmed by how rumours and misperceptions about American policy aims were constantly spreading despite intensive dissemination of information. Rumours speak to the power of interpersonal communication over mass media channels, while the misperceptions speak to the power of the group context to interpret or give meaning to a communication event.

“Directness” was another prominent feature of American messages. “Let me be perfectly clear,” as President Bush said in his warning to Iraq. The US wanted to force a vote on the second UN resolution, Bush explained, “so that we know where people stand. People have to show their cards.” Such an open confrontation or violation of “public face” resonates negatively with cultures that value indirect styles. Such directness was the basis for depictions of America as “aggressive” and a “bully.” Many foreign commentators negatively associated Bush’s directness with the “American cowboy” image and derided America’s aggressive stance. Not surprisingly, many Americans were proud of that “American cowboy” image. American Vice President Dick Cheney was not alone when he described Bush’s cowboy behaviour as “refreshing.”

Similarly characteristic of the American cultural style is a focus on “facts” and “evidence” as primary ingredients of persuasive messages. Hence, Americans tend to gather as many facts as possible and carefully construct an argument. American Secretary of State Colin Powell appeared at the UN numerous times to present the American case. Each time, he forcefully outlined in detail the specific facts in an effort to make a stronger, more compelling argument. The administration felt confident that with new and stronger facts – more evidence – it could rally foreign support. However, in other cultures, metaphors and analogies that suggest important relationships are much more persuasive than impersonal “facts.” Thus, while the facts positively resonated with the American public and reinforced domestic public support, the facts alone failed to resonate with foreign audiences. The “facts” did not persuade these audiences.

Time-focused messages are also in keeping with the American cultural profile. As members of a monochromic and linear culture, Americans tend to adhere to schedules, deadlines, time lines and other forms of time commitments. Time is an important commodity in American culture and keeping one’s time commitment is often seen as an indication of one’s character. Hence, Americans saw Iraq’s failure to meet deadlines as particularly grievous. In contrast, polychronic and non-linear cultures have a more fluid concept of time. Thus, while America tried to focus international attention on the time element as symptomatic of Iraq’s ill intentions, foreign audiences were understandably chagrined by the American rigidity and myopic focus.

The American perspective of “time” was also evident in the future-oriented messages that pervaded American public diplomacy. Americans repeatedly chastised Iraq for “stalling” and “delaying,” anathema to a culture concerned with moving forward. At times, America’s focus on “moving forward” visibly strained relations. American officials said America would “go ahead” with or without the UN or the international community. Many other past- and present-oriented cultures perceived such behaviour as “impatient” or “aggressive.” They urged America to “take the historical perspective” into account and they questioned America’s “rush” to war. Whereas the future-oriented perspective positively resonated with the American public, other publics were not swayed by America’s sense of urgency. The most prominent example of the tensions caused by the differing time orientations was in the American Defence Secretary’s characterisation of “new Europe and old Europe.” Both literally and figuratively, Americans expressed their praise of the “new” and their disdain for the “old.” Ironically, however, while the American public lauded the “new” as a precursor of the future, other nations esteemed the “old” as proof of history and tradition.

These differences of goals, approach and message appeals together reflect and reinforce what appears to be an American style of public diplomacy. The features of this American style closely parallel features of an American cultural profile. However, while the American style positively resonated with the American public, it negatively resonated or failed to resonate with foreign publics that have a different cultural profile.

The Unintended Consequences of Crisis Public Diplomacy

Public diplomacy appears to entail more than simply translating official messages and giving them the widest dissemination possible to a foreign audience. While translation may overcome the language barrier, it may not overcome the cultural barrier. Just as culture shapes the communication of a people, it follows that because communication is at the core of public diplomacy, culture also shapes the public diplomacy of a nation. American public diplomacy initiatives reflect a uniquely American cultural style of communication, public relations and advertising.

Unfortunately, although the American style resonated positively with the American public, it resonated negatively with publics in other cultures. In fact, a communication style that resonates positively within one’s own culture seldom resonates well in another. According to intercultural communication theory, ethnocentric tendencies tend to reinforce the view that one’s own cultural style is not only the right way, but also the only way. Cultural differences are rarely seen as “different,” but more often as “right” and “wrong.” Consequently, while the public diplomacy style of a country may resonate positively with its own domestic public, if it is different from the style of a foreign public, it is likely either not to resonate at all (i.e., be ineffective) or to resonate negatively (be counterproductive) with foreign publics.

A nation cannot communicate with foreign publics in the same way that it communicates with its domestic public and achieve the same response. However, because of the open nature of public diplomacy, a nation cannot segment the domestic from foreign publics so that both receive different communications. What the domestic public hears, the foreign publics hear. Yet, because of an asymmetry of cultural styles, each public interprets the message differently.

The challenge of public diplomacy during crisis and conflict situations becomes the challenge of communicating effectively with culturally different publics simultaneously. Effective public diplomacy must cross the cultural hurdle so that a nation’s public diplomacy positively resonates with one’s domestic and foreign publics.

In the American example, American officials apparently saw “the problem” as a “lack of information.” Thus, they focused on supplying information – making the information available in the native language and disseminating it widely. However, by focusing on language and technical hurdles, without accounting for the cultural differences, Americans may have magnified the problem. They insured that their message reached foreign publics, but they had no control over how the foreign publics interpreted that message.

The problem may have been made worse in that America was facing a crisis or conflict situation. Traditional public diplomacy tends to focus on long-term education, culture and information programmes aimed at favourable or neutral publics. Crisis public diplomacy is distinct from traditional public diplomacy in that it often entails communicating simultaneously with multiple audiences, including hostile publics, in a rapidly changing, highly visible and competitive communication environment. Additionally, during times of conflict, rallying domestic support often means identifying a foreign enemy. If the foreign public identifies with the “foreign enemy,” efforts to demonise the enemy will only further alienate the foreign public.

The most important factor in crisis public diplomacy, however, is the asymmetry of cultural styles among publics. If there is an asymmetry of cultural styles, a nation’s efforts to intensify its public diplomacy may inadvertently magnify cultural differences between the domestic and foreign publics and amplify international misunderstandings.

For Americans, the war on terrorism and Iraq was part of the American solution to address that crisis. In response to this crisis, America intensified its public diplomacy. It tried to amplify its message through stronger language and vigorous dissemination. Because of the positive resonance, American domestic support grew. However, because of negative resonance, foreign support weakened and anti-American sentiment grew. While American officials were able to control their message domestically and achieve the public response they wanted, it appears they lost control of their message internationally. Rather than achieving positive results, American public diplomacy efforts yielded negative results.

The more America intensified its efforts, relying exclusively on American style public diplomacy, the wider became the gap between the domestic and foreign publics. Instead of increased understanding and support, the result was increased misunderstanding and tension. Instead of achieving greater international unity, divisions became more pronounced and America became increasingly isolated within the international community. None of this was intended. This result, based on asymmetry of cultural styles of public diplomacy, is what I call the unintended consequences of crisis public diplomacy.

Summary and Conclusion

This essay examines how intercultural communication differences among nations can inadvertently magnify tensions during a crisis when nations rely on their own cultural style of public diplomacy to communicate with foreign publics. Beginning with posing the question of how American efforts to intensify its public diplomacy efforts resulted in declining support, public diplomacy was examined as a communication phenomenon, as opposed to a purely political phenomenon. From there, a review of cultural differences in communication styles illustrated America’s cultural style of communication. American cultural communication patterns are incorporated within the American style of public diplomacy. While this American style of public diplomacy resonated positively with the American domestic public, it resonated negatively or failed to resonate with foreign publics. This asymmetry of cultural styles produced different perceptions and responses to American public diplomacy. The more America intensified its public diplomacy efforts, the greater the gap became between America’s domestic and foreign publics. This widening gap between the domestic and foreign publics is the unintended consequence of crisis public diplomacy.