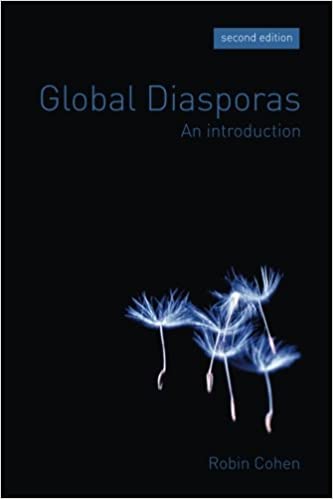

My contribution to this volume on diplomacy and intercultural communication will consist of some reflections on the importance and essence of the foreign cultural policy of states. We frequently hear people talking about the tendency towards globalization, for instance, in the emergence—or existence already—of the world as a global village. However, the tendency towards nationalism, at its height in the 19th century, has seen its prolongation, at least in the political field, in the 20th century, especially in the second half. During this time quite a number of new or newly independent states emerged, in the first category, for instance, Slovakia, in the second, the Central Asian republics.

The state of cultural relations in the world has been influenced by this double evolution, the more so because cultural factors, as part of identity formation, have been at their origins. This said, we do not see any contradiction between the idea of a globalized world and the idea of a diversity of cultures. We would even deplore any tendency towards a globalization of cultures—which should be radically opposed because a variety of cultures enriches not only each of us but also, should it come about, a globalized world.

Culture, in the best case, is what a people, a society, each of us has deep inside us: a positive force or conviction and not an attitude against others. Only because Huntington did not understand this could he write his book on clashes of civilization, which, in fact, he considers a glorification of Western culture, American style, that has to stay victorious in the world. This is neither a fair description nor a fruitful coexistence of the various cultures in the world that enrich our lives. However, such an enrichment is precisely what we strive for.

Another basic issue we should consider before we engage in a discussion on international cultural intercourse is the importance of culture in national life. You may remember the German saying that a prophet is not recognized in his own country. As in every saying, a kernel of truth may be found in it. I would like to give you an example concerning my country. Recently, the internationally known exhibition curator Harald Szeemann wrote: “Switzerland is blessed as a country; it is a land of hoarders whose sense of the past prevents it from looking to the future. But it is also home to many exciting, committed spirits, creative and resourceful. Regrettably, the body of the people remain little affected by this. Otherwise, I enjoy setting out from here as a mercenary and then coming home to the isolation of Ticino’s valleys to think up new adventures in peace and tranquillity.”

At least in old-fashioned Western societies, artists have often been, through the centuries, the avant-garde of social life, rarely understood and therefore often underestimated; at best, they have been seen as useful to further, with their art, the prestige of the powerful of their time. Only a few were luckier and dedicated works to the glory of God, the only one they believed deserved such glory.

I do not want to suggest by this that real art must have a religious basis. I would suggest, rather, that art, if it has a finality, should serve the enrichment and progress of something superior to the political, social, or military establishment—meaning today that it should enrich mankind. This is rather abstract, but it is more concrete in its negative meaning: art should not serve a socio-political entity.

Here, I have to make my third introductory remark, namely that I do not find it useful to engage you in a search for identity. Such searches prevent you from concentrating on the essential, namely to be open to the world; to be open to give and to be open to receive. In fact, identity means something distinct from others; it is defined by comparison to the other. Identity is described by indicating its boundaries. The presumption is that what is inside these boundaries is of superior quality to what is outside, as, in the Middle Ages, a city’s preferential legal status was confined to the city walls, or the entity limited (and protected) by the Great Wall of China, by the wall of Alexander the Great, or, in Europe at the time, Hadrian’s Wall. As you remember, the Romans called all people living outside the borders of their Empire “barbarians;” the “Roman” identity therefore meant urban, civilized. It is obvious for us today that such a description not only hinders international communication, but is definitively wrong in substance, because any of the people on our Earth throughout history have, at a given moment, contributed to cultural evolution. It is, above all, a matter of perception. An Iranian can tell you about the formidable cultural achievements of the Mongolians in his country, for example, in architecture, whereas Western Europeans would describe Mongolians, or Huns, as they used to call them, as devastating, despite their significant influence on Eastern European music, for example.

Foreign Cultural Policy of States as Intercultural Communication

This brings me to the question: What, then, are we talking about? International diplomacy should be, in the best case, a form of intercultural communication. As we have seen, many forms of intercultural communication are possible. When we speak about international diplomacy in the form of foreign cultural policy of states, then we deal with a specific form of intercultural communication.

The constituent elements are that

a) it is related to transborder cultural communication;

b) the propagators of this communication are states;

c) the main actors are people who create or perform arts; and

d) the audience of foreign cultural policy of states is only to a small extent governments, and to a much larger extent, the people.

In general terms, one of the traditional difficulties in communication in interstate relations is the language issue. Today, there is no lingua franca, as Latin was in Europe hundreds of years ago. On the world level, Spanish might be as important as English, but Arabic, Chinese, French and Russian are equally important languages of the United Nations. Thus, we need to resort to the assistance of interpreters in international conferences, sometimes even in bilateral relations.

Culture, however, communicates easily with other cultures without words. The interpreters who master the language of culture are not language interpreters but creative artists. This is the main reason for the overriding importance of cultural relations, therefore, also cultural communication, over traditional political and economic relations. Political and economic relations have a tendency to vary in their degree of importance and strength, since they depend to a large, almost exclusive extent, on the self-interests of the actors. Whenever their interests match, you speak of close and excellent relations; when they only match in some sectors, you speak about relations that are more difficult.

Of course, cultural relations can also exist to a greater or lesser extent; but even if they exist only to a minor extent, they are conceived and understood as positive and fundamental. By whom? Not only by governments and some important economies, but also by the people. Intercultural communication, including the cultural foreign policy of states, is designed in the first place to connect people, rather than state actors acting on behalf of the people. This is so because of the very nature of the language of culture.

Now, clearly, some individuals, by nature or education, are more receptive than others, but no one is excluded from this communication system. Here, mass media will have to play a role as multiplier, in order to ease access to communications systems and to make them better understood by everybody.

Why then, and this will be the next question, does cultural foreign policy of states not occupy a more prominent place in the field of international relations? Clearly, its impact is not only long-lasting but also deep, since it reaches the people themselves quite directly, not only governments and administrations.

The reason is that cultural foreign policy of states not only presupposes inside knowledge of governments and administrations but also a major effort to join forces with artists (in the broad meaning of the word). As long as governments and administrations are of the opinion that art is something nice for the evening, after “serious” work, not much effort will be invested in the promotion of cultural foreign policy.

This is not an issue of quantity but an issue of quality. It is not sufficient to simply increase activities in cultural leisure; one must understand that culture is more than leisure. Culture is, in the true sense of the word, vital. Accordingly, the effort requires a change of mindset that is, in most cases, difficult to achieve.

It is my experience that many civil servants refrain from making initial efforts in cultural communication. They ignore how rewarding participation in cultural communication may be. Sometimes, as well, existing prejudices make relationships between artists and civil servants more difficult. Above all, civil servants in a ministry willing to make the effort do not always connect well with their top structure.

Improving Intercultural Communication

Hence, some further investments are needed in order to improve intercultural communication. I think the primary investment has to be made in building the awareness and capacity of the staff of government service branches. This is not an easy process. It will be time-consuming and has to be intensive. Part of it should consist in seeing that good performance in cultural communication is rewarded career-wise. Up to now, in many ministries economic business promotion has been rediscovered and is very much in the forefront; cultural foreign policy in ministries of foreign affairs should have at least equal ranking.

Even more difficult will be to build up, where it does not exist yet, embassy sections to work as solid participants and, in the best case, partners in intercultural communication networking. To achieve this, a minimum of funds must be available at the discretion of these sections.

The results of these changes may be striking: embassies, whose role is mostly misperceived by the civil society of the receiving state, will all of a sudden become partners of civil society, in addition to their traditional role as partners of governments. In its turn, this will facilitate the fulfillment of the more traditional tasks of the embassies with government services.

Having reached a better status, embassies will also discover through their newly acquired networks that their nationals residing as artists in receiving states are, by their activities, already forging very basic ties of understanding between the people of the sending and the people of the receiving states.

At this point, foreign cultural policy will start to show its first results. You will have realized by now that in reality translation of a genuine cultural foreign policy into practice is less a matter of words than of deeds and that for many government services hard work has to be done in order to become a credible player in the so much needed global intercultural communication.

Foreign cultural policy is in itself vital for establishing long-lasting and deep relations between countries in international intercourse. But what we should equally bear in mind is what I have said at the outset of this presentation, namely that it is important to preserve the variety and the diversity of cultures in our efforts to bring about global cultural communication. Uniform culture is not culture and cannot be communicated.