Radio and TV broadcasting: Diplomacy going live

Visit the other stops on our journey:

This month, we will talk about radio and TV broadcasting and the influence it had on diplomacy.

The invention of wireless communication

Last month, we discussed the invention of wireless communications, the invention that had many fathers, including Maxwell, Hertz, Branly, Lodge, Popov, Tesla, Bose, and Marconi. They provided the scientific foundation on which the technology of radio communication was to develop as a way of transmitting sound via radio waves.

Transmitting sound via radio waves

Both Marconi and Reginald Fessenden were attempting to create a wireless telephone by combining two inventions: the telephone and wireless communication. In line with the principle of unintended consequences, their pursuit resulted in something else: a ‘radio music box’. Instead of a wireless telephone (two-way communication), we got a ‘radio music box’ (one-way communication). The simplicity of this device was the very reason why radio broadcasting proved to be a powerful communications tool.

Both Marconi and Reginald Fessenden were attempting to create a wireless telephone by combining two inventions: the telephone and wireless communication. In line with the principle of unintended consequences, their pursuit resulted in something else: a ‘radio music box’. Instead of a wireless telephone (two-way communication), we got a ‘radio music box’ (one-way communication). The simplicity of this device was the very reason why radio broadcasting proved to be a powerful communications tool.

The first radio broadcast

Reginald Fessenden carried out the first-ever radio broadcast with speech and music. On Christmas Eve of 1906, from a radio station in Bryant Rock, Massachusetts, he transmitted a violin performance and read a Christmas greeting himself. The wireless broadcast reached ships over a radius of more than 150 km.

Reginald Fessenden carried out the first-ever radio broadcast with speech and music. On Christmas Eve of 1906, from a radio station in Bryant Rock, Massachusetts, he transmitted a violin performance and read a Christmas greeting himself. The wireless broadcast reached ships over a radius of more than 150 km.

The Marconi Company began to broadcast from Chelmsford, Essex, in 1920. Marconi engineers broadcast music instead of simple, dull test messages. Due to the fear of the commercialisation of the radio, and the military's claim on unoccupied airwaves, the British Post Office placed a ban on these daily broadcasts and ruled that experimental broadcasts must be individually licensed.

The establishment of the BBC

In 1922, the British Post Office gave permission to the Marconi Company to broadcast 15 minutes of music programms per week. Soon, another experimental station was set up in London. The British government realised the potential of the radio and the need to regulate it. On 18 October 1922, the British Broadcasting Company (the original name of the BBC) was established in order to monitor the development of the industry.

By the 1940s, 83% of Americans and almost 35% of British people owned a radio. A decade later, this number doubled, after which the TV slowly began to replace the radio as the favorite medium.

The power of radio broadcasting

For centuries, the main medium of public diplomacy was the printed press. Gutenberg's invention played an important role in diplomatic and religious struggles.

The politicians understood the power of the radio quite early, between WWI and WWII. For the first time, they could address the wider population directly via radio, without having their message filtered by the press.

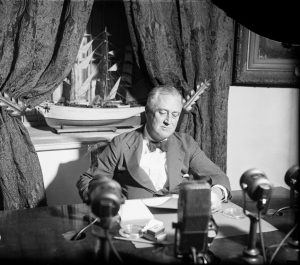

The fireside chats

It was during this period that the basic radio propaganda infrastructure was established.

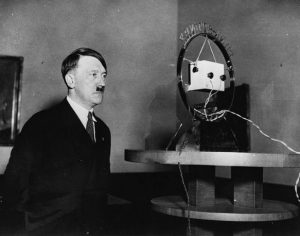

The Nazi propaganda

Joseph Goebbels

The established technology dynamics continued during and after WWII. It is said that the radio was the most significant tool that influenced the outcome of the war. It was used both as a propaganda and morale-boosting tool by all sides.

Radio as morale-boosting tool

Winston Churchill spoke directly to the people via the BBC during WWII

As the radio took readers away from printed press, the press tried to discredit the radio as a news source. The newspaper industry sensationalised the panic that Welles’ episode created, to prove to advertisers and regulators that radio management was irresponsible and not to be trusted.

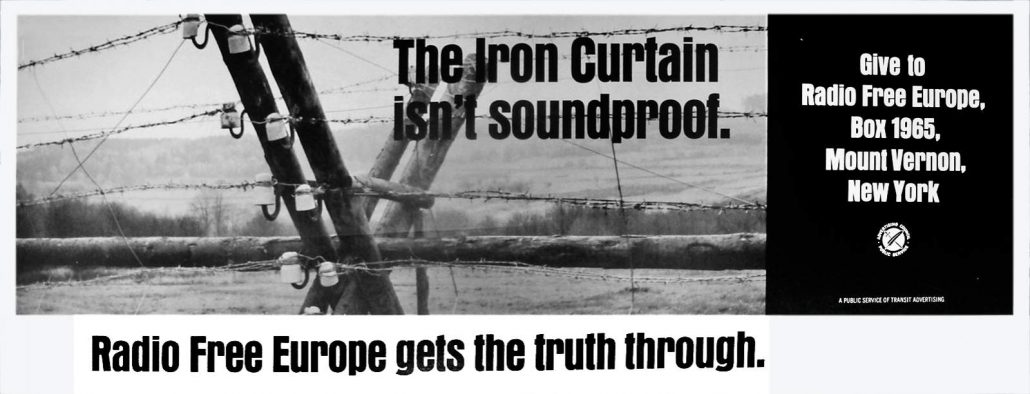

The Cold War: An ideological battle via radio waves

The radio-broadcasting infrastructure, established during WWII, found another use during the Cold War. International broadcasting increased, and contained propaganda disguised as news. Communist and anti-communist states attempted to influence each other's domestic population.

The USA established the Voice of America in 1942, which continued operating after WWII ended. In 1950 Radio Free Europe started to operate, and Radio Liberty in 1951. In 1947, the Voice of America started broadcasts in the Soviet Union as a part of the US foreign policy to fight Soviet propaganda. This resulted in the aggressive jamming of Voice of America’s broadcasts by the Soviets.

While objecting to Western radio broadcasting, the USSR developed a similar, if not even more powerful radio system, covering almost the entire globe – Radio Moscow.

In Great Britain, through Churchill’s mastery of the medium, the BBC underwent a big expansion. At the end of WWII, the BBC increased the number of broadcasting languages to 45, as well as its transmitting power. The Axis powers used to broadcast in many languages as well.

Radio broadcasting as a diplomatic issue

Radio broadcasting entered international relations and the diplomatic arena very early. Many governments worldwide realised the power of the radio in reaching foreign audiences. We got a new way of conducting diplomacy: public diplomacy.

In 1936, the League of Nations drafted a treaty called The International Convention Concerning the Use of Broadcasting in the Cause of Peace, where states agreed to prohibit the use of broadcasting for propaganda or spreading false news. The effect of this convention was limited, since Germany, Italy, and Japan weren’t parties of the convention. In addition, China, the USA, and the Soviet Union didn’t ratify it.

Jamming of radio programmes

Another diplomatic issue was the jamming of radio programms which became an important issue in diplomatic negotiations during the Cold War. Politicians on both sides had an issue with ideas being transmitted across borders. The Western Bloc believed that states could not exercise sovereignty over words and ideas broadcast via radio. On the other hand, the Eastern Bloc claimed that states had a duty to jam information when those ideas criticized the socialist order. These positions mark the outlines of the debate over the freedom of information.

The USSR heavily used radio jamming to prevent its citizens from listening to, for the Communist Party, politically dangerous broadcasts by the BBC, the Voice of America, and other Western broadcasters. The USA also jammed Radio Moscow, Radio Pyongyang, and Radio Havana Cuba, but on a smaller scale.

The UN resolution of 1950 condemned the Soviet Union's deliberate distruption of radio signals as 'a violation of the accepted principles of freedom of information'. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union continued to jam foreign broadcasts.

The practice of jamming remained a diplomatic issue until the end of the Cold War.

The future of the radio

Radio broadcasting confirms that technological advances usually coexist with previous innovations, in spite of various ‘endism’ predictions. The telegraph did not replace traditional mail, nor did the telephone ‘kill’ the telegraph. Radio coexists with TV. In fact, with the exception of the telegraph, most communications innovations introduced during the last two centuries, including postal mail, the telephone, radio, TV, and fax, are still in use today. Postal mail, one of the oldest organised communication methods, is a growing business even today (e.g. DHL, FedEx).

Radio broadcasting was reborn with online radio stations, and later with podcasts that gained popularity in the last ten years. Both podcasts and the radio are mediums a lot of people are turning to as they allow you to multitask while listening to music, the news, or talk shows.

Early years of television

Since its invention in 1926, and the beginning of its commercial use six years later by the BBC, television has become the main news and entertainment medium, and it will keep this position for many years to come. During the 1970s and 1980s (the so-called 'the golden years of television'), prime-time television (the time period when the audience is the largest) developed as a new way of addressing a great number of people. It became an integral part of our daily routines. For the first time, we were able to see and hear world news as it happened.

Countries and diplomats started using TV as a quick source of information, and as a powerful tool to convey their messages.

The mechanical television

The success and popularity of the radio prompted research in the field of transmitting moving pictures. It is difficult to say who invented television and when exactly. There were a great number of inventors in various countries that worked simultaneously to achieve the same goal during the 1920s.

Two inventors, John Logie Baird from Britain and Charles Francis Jenkins from the USA, built the world’s first successful mechanical televisions. By 1929, Baird managed to produce half-hour shows for the BBC three times a week.

The electronic television

Russian inventor Vladimir Zworykin and US inventor Philo Farnsworth were the pioneers of the electronic television. Zworkyn invented a workable cathode-ray receiver called the kinescope, while Farnsworth, with his image dissector camera tube, transmitted the first live human image in 1928.

In 1938, the first electronic TV sets became commercially available in the USA. A year later, the opening of the 1939 New York World's Fair was broadcast on TV with a speech by president Roosevelt, the first American president to appear on TV. By the late 1950s, most European countries broadcast their own TV programms, while less developed nations soon followed.

The golden age of television

The problem with television is that people must sit and keep their eyes glued on a screen; the average American family hasn’t time for it.

J.W. Ridgeway, chairman of the UK Radio Industry Council, said:

It is inevitable that television will become the primary service and sound radio the secondary one.

The next four decades were the golden age of television. In 1963, Americans found TV to be a more reliable source of information than the press. Prime-time news, reportages, documentaries, and live coverages reached a larger audience than any media ever before. CNN, the first TV channel devoted to broadcasting news 24 hours a day, was established in 1979.

Diplomacy going live: The CNN effect

The possibility of shaping public opinion was most prominent during the First Gulf War (1991) in Iraq. CNN had reporters and cameras on the ground, reporting the conflict ‘live’. The CNN team broadcast live from the Rashid Hotel in Baghdad when no other network was able to. Their coverage was broadcast unedited, with an exciting, dramatic narrative. The real-time news coverage increased transparency, but complicated the sensitive diplomatic relationships between states.

The 'CNN effect'

The 'CNN effect'

This led some to formulate the theory of the ‘CNN effect’, a new phenomenon in foreign relations. According to it, global TV networks played a significant role in determining the actions diplomats would take, as well as outcomes. The CNN effect works through shaping public perception, which then affects diplomatic agendas. This theory originates from the 1990s when CNN had real-time coverage of interventions in Iraq, Somalia, and the Balkans.

The strong presence of media in the Middle Eastern conflict created space for local broadcasting agencies, such as Al Jazeera, which tries to provide a different perspective from that of global agencies.

The impact of the television on diplomacy

For diplomats, TV has been a source of quickly updated and available information. It also accelerated the speed of diplomatic communication. TV has focused the world's attention on global issues such as terrorism, global warming, and human rights, and sometimes leaders had to address these issues even when they were not among the priorities.

As Eytan Gilboa noticed, the participation of media in diplomacy became important as government and non-government actors increasingly used the media as a major negotiation tool. In the information age, the involvement (and sometimes exclusion) of the media in diplomatic affairs can have a strong impact on negotiations.

Television is still powerful and important in today’s diplomacy. It is important in shaping public opinion, and the general public still relies on traditional TV channels as the principal source of information.

The future of television

Nowadays, TV channels are increasingly streaming over the internet. Viewers can watch news and TV shows whenever and wherever they want.

The evolution of television will continue in the coming years. With new technology and new forms of entertainment, television will continue to transform into a personalised experience. It collects data based on users' watch history, demographics, and preferences, and algorithms determine unique content for each viewer.

In addition, TV will probably become immersive. Instead of passive watching, users will be able to participate and interact. Streaming services, like Netflix, are experimenting with interactive content (e.g. viewer choices affect a series plot).

In conclusion, television will probably remain a channel for public diplomacy, even though it will be completely different than it was a few decades ago.

Meanwhile… The history of TV broadcasting in Africa

Although the birth of TV broadcasting in Europe and North America is widely known, the evolution of TV in Africa is less known. The establishment of a Moroccan TV station in 1954 marked the beginning of the TV age in Africa. In 1959, the Western Nigeria Television Service broadcast the first terrestrial TV signals on the continent.

Zimbabwe's first broadcasts came in November 1960, when black and white programming started in Harare. Algeria, Kenya, Uganda, and Senegal launched TV stations in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Some countries like South Africa and Cameroon didn't have TV stations until the 1970s and 1980s.

Nigeria was a front runner in introducing news and specific genres, and Nigerian television became the mouthpiece of the government.

Between 1980 and 1985, NTA started producing Africa’s first local soap operas, children’s programms, and comedy series. This marked the birth of the Nollywood film industry, which now produces more than 50 films per week. It surpassed Hollywood as the world’s second-largest movie industry by numbers of productions, after India’s Bollywood.

Cheers! Martini

In its simplest form, Martini is a cocktail. It's a mix of gin and vermouth, garnished with an olive or a lemon. The name may have derived from the Martini brand of vermouth. Another popular theory suggests it evolved from a cocktail called the Martinez served sometime in the early 1860s.

While it's broadly thought that the Martini is an American invention, the cocktail first became popular in Europe. It was the favourite drink of the British prime minister Winston Churchill. Vermouth was usually made in Italy and France. As WWII progressed, Britain stopped getting shipments from either of these countries. However, this did not obstruct Churchill's Martini drinking. At the time, he joked: 'The only way to make a Martini is with ice-cold gin, and a bow in the direction of France.'

A 'Martini kit'

Martini was also Ernest Hemingway’s drink of choice. He paid tribute to the drink in his 1929 novel A Farewell to Arms, with the immortal line: 'I had never tasted anything so cool and clean. They made me feel civilized.'

During the 1950s and 1960s, the 'three-Martini lunch' was a widespread practice of executives and businesspeople.

The popularity of the Martini rocketed with Ian Fleming’s secret agent James Bond. His famous quote 'A Martini. Shaken, not stirred.' is part of cinematic history. Bond drinks his Martini with vodka instead of gin. Also, 'shaken' is the opposite way of how we usually drink a Martini.

Cheers!

Watch the recording of our October Masterclass Radio and TV broadcasting: Diplomacy going live. Consult the PPT presentation.

Recordings from all sessions are available on our YouTube channel.

[Recording]

For more information on this topic, you can consult the following resources:

Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man - Chapter 1 | Medium is the Message

Author: Marshal McLuhan

Investigates the central ideas of Marshall McLuhan. Examines the reaction of others to his views and points out that his interest is the impact of electronic technology on the contemporary world.

Diplomacy in the media age: Three models of uses and effects

Author: Eytan Gilboa

This study offers three conceptual models to promote systematic research into uses of the media as a major instrument of foreign policy and international negotiations: public diplomacy, where state and nonstate actors use the media and other channels of communication to influence public opinion in foreign societies; media diplomacy, where officials use the media to communicate with actors and to promote conflict resolution; and media-broker diplomacy, where journalists temporarily assume the role of diplomats and serve as mediators in international negotiations.

The first two models, while previously defined, undergo serious revision in this study. The third model is new. This article demonstrates the analytical usefulness of the models through applications to various examples and case studies of significant contemporary diplomatic processes.

Clarifying the CNN effect: An Examination of Media Effects According to Type of Military Intervention

Author: Steven Livingston

Jamming and the Law of International Communications

Author: Rochelle B. Price, 1984, University of Michigan Law School

Mapping World Communication (War, Progress, Culture)

Author: Mattelard A (1994)

Translated by Susan Emanuel and James A. Cohen, The University of Minnesota Press

Armand Mattelart offers a history of modern communications that exposes the connection between militarism and the evolution of the media industry, while questioning the notion that technological innovation is always synonymous with progress. The history of modern media emerges in this account largely as a history of state control, wielded to discipline internal populations and combat external enemies.

Mattelart moves from the rise of the postal stamp to international telegraphy to the world press, and finds in each the hand of state strategy. In his analysis of the Gulf War, we see how the media can go beyond ideological service to become a tactical weapon. Beyond war and geopolitics, he examines the role of intensified economic competition in the forging of new international networks of information and communication, raising the fateful question of whether the emergence of these networks will lead to a uniform "world culture" or rather to greater fragmentation of the planet.

Dynamics of Modern Communication: The Shaping and Impact of New Telecommunication Technologies.

Author, Flichy P (1995), Sage Publications

Combining political economy with the sociology of innovation, Dynamics of Modern Communication is a comprehensive social history of communication technology from 1790 to the present. Author Patrice Flichy presents a careful critique and historical analysis of the social shaping and impact of the major communication technologies of the past 200 years. From the semaphore and telegraph to contemporary information technologies like the phonograph, photograph, telephone, radio, cinema, and television, this book focuses on the relationship between technological change and the social changes in which they were situated.

The Practice of Diplomacy

Authors: Hamilton K and Langhorne R (1995) Routledge

Practice of Diplomacy has become established as a classic text in the study of diplomacy. The topics include: discussion of Ancient and non-European diplomacy including a more thorough treatment of pre-Hellenic and Muslim diplomacy and the diplomatic methods prevalent in the inter-state system of the Indian sub-continent; evaluation of human rights diplomacy from the nineteenth-century campaign against the slave trade onwards.

A fully updated and revised account of the inter-war years and the diplomacy of the Cold War, drawing on the latest scholarship in the field; an entirely new chapter discussing core issues such as climate change; NGOs and coalitions of NGOs; trans-national corporations; foreign ministries and IGOs; the revolution in electronic communications; public diplomacy; transformational diplomacy and faith-based diplomacy.

The Rise of Modern Diplomacy 1450-1919

Author: M.S. Anderson, (1993), Longman

Though international relations and the rise and fall of European states are widely studied, little is available to students and non-specialists on the origins, development and operation of the diplomatic system through which these relations were conducted and regulated. Similarly neglected are the larger ideas and aspirations of international diplomacy that gradually emerged from its immediate functions.

The Invisible Weapon: Telecommunications and International Politics 1851-1945

Author: Headrick DR (1991) Oxford University Press

Telecommunication is, and always has been, a political technology, as the timely flow of information is a vital instrument of power. Headrick argues that telecommunication gives people options, not orders. During periods of peace, cables and radio were, as many had predicted, instruments of peace; in times of tension, they became instruments of politics, tools for rival interests, and weapons of war.

The book illuminates the political aspects of information technology: the speed of telegraphy, which could diffuse conflicts in far-flung empires, but which also hastened the deterioration of diplomacy on the brink of the First World War; the broad coverage of radio, which increased public knowledge and public pressure on governments, and consequently the political interest in controlling news; and the security of telecommunications, which made communications strategy, communications intelligence, and cryptography decisive tools during the two World Wars

Browse through the list of videos related to the radio and TV broadcasting througout the history, and the way it influenced diplomacy:

The 'CNN effect'

The 'CNN effect'