Ancient Diplomacy: What can it teach us?

Visit the other stops on our journey:

In the third session of our monthly Zoom series Diplomacy and Technology: A historical journey, a masterclass with Jovan Kurbalija, we focused on ancient diplomacy.

We started with the emergence of writing, one of the most important communication technologies in the history of mankind (and diplomacy), and navigated through the rich diplomatic heritage of Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt, Assyria, Persia, ancient China, and ancient India. In this journey that covered a few thousand years, we looked for insights that could help us better understand our times and the future of diplomacy.

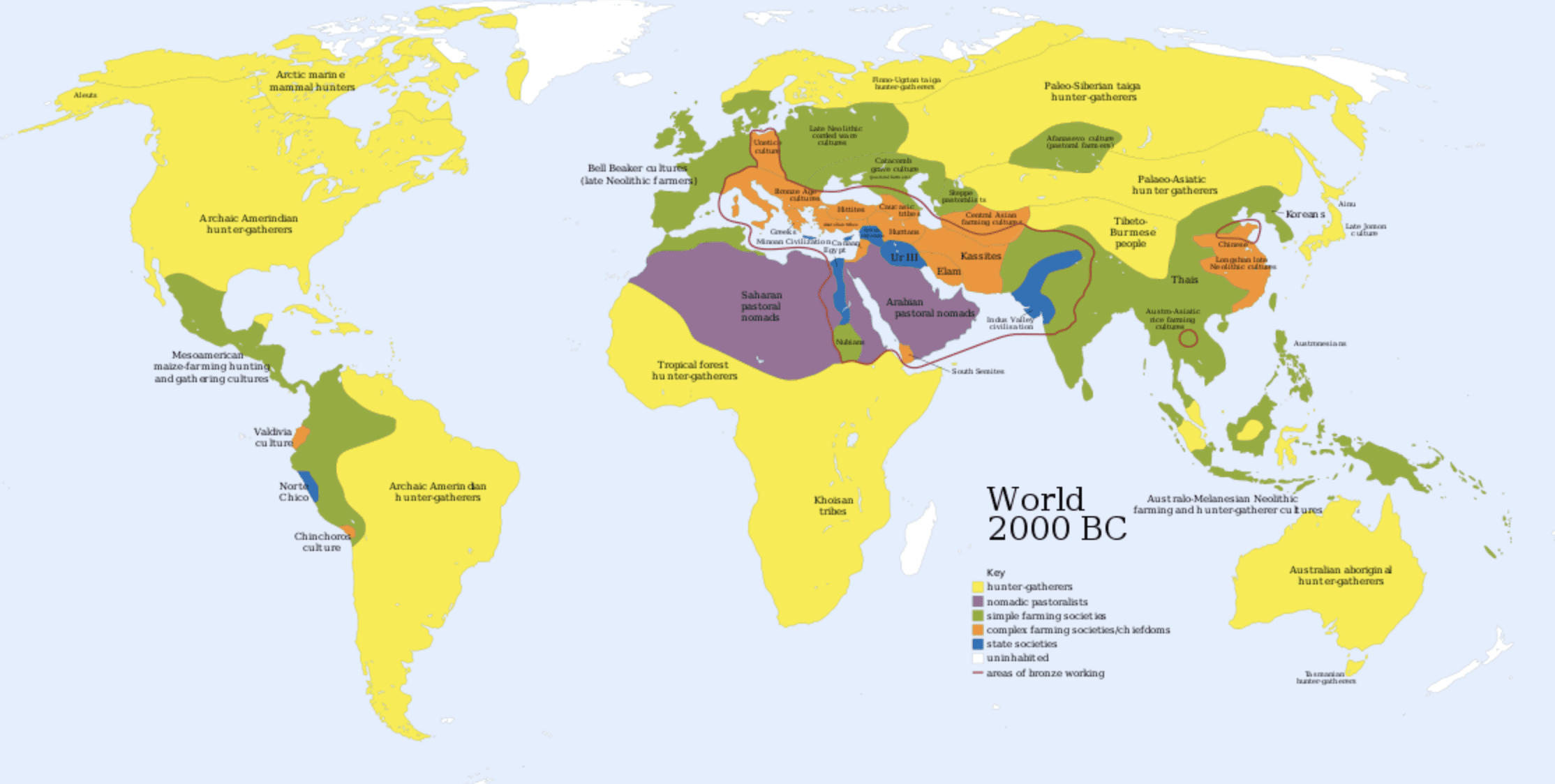

Geopolitics of the ancient world

Civilisational achievements in diplomacy developed all over the world concurrently. Besides Europe and the Middle East, there are examples of diplomacy and advanced ancient civilisations in China, India, Africa, and the Americas.

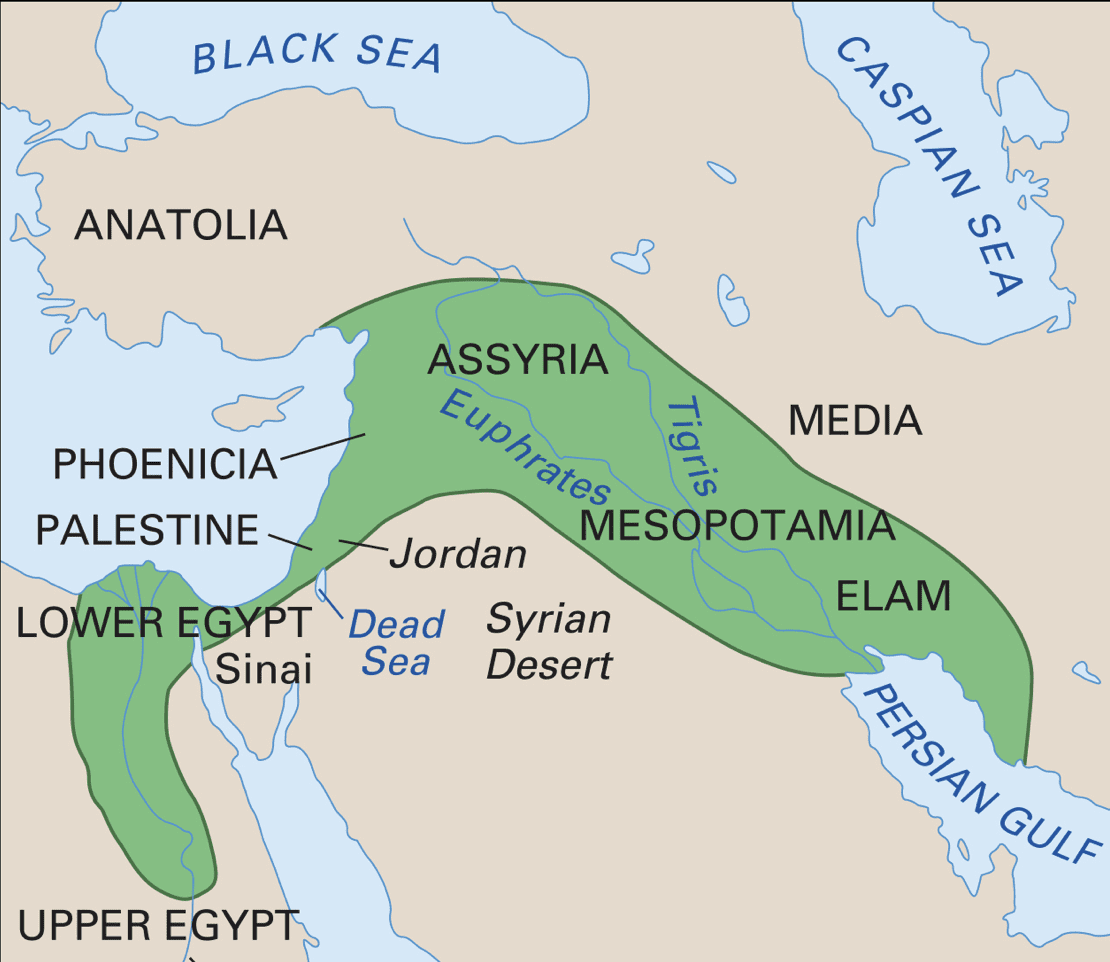

Around the 4th millennium BC, in the region of the Fertile Crescent, covering Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) and the Eastern Mediterranean, the hunter-gatherer society was slowly making room for a new period in which humans began cultivating plants, breeding animals for food, and forming permanent (sedentary) settlements, which would later develop into the first states.

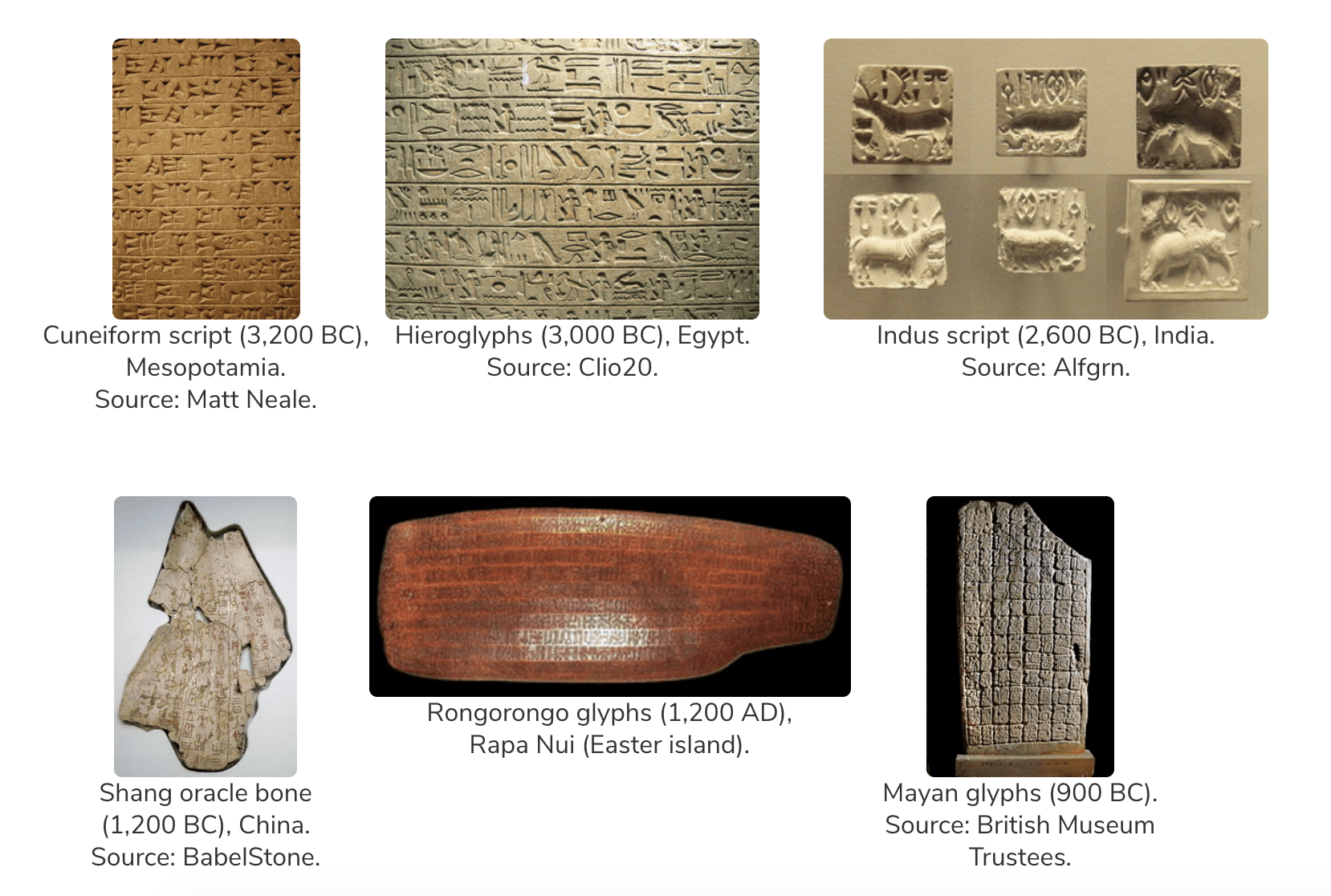

In this period, along with agriculture and the domestication of animals, writing emerged as a key way of conveying knowledge, conserving human experience, and developing diplomacy.

Writing as the key ancient diplomatic ‘technology’

Writing is central to our discussion on the interplay between diplomacy and technology. It was, is, and will remain the key diplomatic 'technology'. Describing writing as a technology might sound counter-intuitive. Although writing is deeply integrated into the way we live and work, it is not a natural faculty like walking and speaking. It was invented, and required tools and skills, and these are the defining elements of technology. Like all other technologies, writing has shaped our way of life.

The transition from prehistory to ancient history can be traced back to the 4th millennium BC when writing was invented by the Sumerians. Archaeological evidence in the form of clay tablets containing the first texts written in cuneiform writing were discovered. Around 3,200 BC, writing also began in ancient Egypt. By 1,300 BC, a fully operational writing system was used in the late Shang dynasty in China. Between 900 BC and 600 BC, writing also appeared in the cultures of Mesoamerica, a historical region in North America. There are also several places, such as the Indus river valley and Rapa Nui (Easter Island) where writing may have been invented, but it remains undeciphered.

Although these dates suggest that writing could have spread out from one central point of origin, there is little evidence of any links between these systems, with each possessing its own unique qualities.

Till this very day, one of the most powerful criticisms of the impact of technology can be found in Plato’s Phaedrus where Socrates narrates how Theuth (Thoth), the Egyptian god of inventions, tried to persuade the sceptical Egyptian king Thamus (Ammon) about the value of the new invention – writing. In the process, Socrates faulted writing for weakening the necessity and power of memory, and for allowing the 'pretense of understanding', rather than 'true understanding'.

Thamus noted the following:

For this invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them.

Mesopotamian diplomacy

Sumerians, the early inhabitants of Mesopotamia, invented writing sometime in the 4th millennium BC, but before writing was developed sufficiently enough to convey words accurately, couriers had to memorise the message and deliver it to the recipient. The poem 'Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta', written in Sumerian around 2,750 BC, tells about the role of messengers of the time.

The extinct Akkadian language was the first diplomatic language. It was a form of lingua franca and the international tongue of the Middle East until it was replaced by Aramaic. Archaeologists discovered the first written diplomatic documents on clay tablets using cuneiform characters that dated back to c.2,500 BC. An important diplomatic correspondence from circa 1,300 BC (the treaty between Egypt and the Hittites) was written in Akkadian (Babylonian). The Akkadian term ‘mar shipri’, which first appeared in texts at the end of the 3rd millennium BC, may designate a ‘messenger’, ‘envoy’, ‘agent’, ‘deputy’, ‘ambassador’, or ‘diplomat’.

In the Babylon era, during the rule of Hammurabi (18th century BC), a highly functional system of messengers was developed. According to the book From the Mari Archives (An Anthology of Old Babylonian Letters), in the same period, there was a well-developed system of envoys ranging from simple messengers to ‘plenipotential ambassadors’ empowered to negotiate agreements on behalf of their masters. The Mari archives also included the first references to diplomatic immunities, diplomatic passports, and letters of accreditation.

Hammurabi is best known for issuing the Code of Hammurabi, the first legal code. If you remove the harsh punishments, which the code had, you can find important diplomatic techniques that we are missing today. Hammurabi understood the phrase ‘skin in the game’ quite literally, and believed it to be a very important legal aspect: builders who built a building that later collapsed and killed people, also needed to be killed. In this way, he held them existentially accountable. He paid attention to align incentives, manage risk, and most importantly, he communicated legal rules and standards in a simple and understandable language to his citizens.

Ancient Egypt: Amarna diplomacy

Three centuries after Babylonia, Amarna diplomacy emerged. It is usually singled out as having the most developed diplomatic system among the ancient civilisations, comprising the main diplomatic techniques, including the sending of representatives, negotiating, and the handing out of immunities.

Amarna diplomacy is named after the Egyptian city of Tel-el Amarna where archaeologists discovered the first diplomatic archive – the Amarna Letters. Tel-el Amarna was established by Akhenaten, and served as the new capital of Egypt until the end of the 18th dynasty. Akhenaten was a leader inclined to changes. He began a religious revolution in which he declared Aten was a supreme god, and turned his back on the old traditions. The dynasties of the New Kingdom of Egypt oversaw a period of extensive creativity, particularly noticeable in architecture. Additionally, diplomacy was favoured over war.

During the reign of Ramses II, the first peace treaty, the Treaty of Kadesh, was signed.

After the Battle of Kadesh, today considered a draw, both the Egyptian and Hittitian sides decided to end the hostilities between the two nations. The two kings, Ramses II and Hattusili III, came to realise that neither could substantially gain advantage of the other and the best course was the path of peace. The Hittites and Egyptians then entered into a new relationship in which they shared their knowledge and experiences. The Hittites taught the Egyptians how to make superior weapons and tools while the Egyptians, masters of agriculture, shared their own knowledge with the Hittites. The two nations continued a mutually beneficial relationship until the fall of the Hittite Empire c.1,200 BC

Amarna Letters

The Amarna Letters, discovered in 1887, present an archive written on clay tablets (382 tablets were discovered) primarily consisting of diplomatic correspondence between the Egyptian administration and the leaders of neighbouring kingdoms. The name of the letters derives from the place where the tablets were found: the ancient city of Akhetaten in Egypt, built by order of Pharaoh Akhenaten, and today known as Tell el-Amarna.

The tablets cover the reigns of Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and possibly Smenkhkare or Tutankhamun, from the 18th dynasty of Egypt. The system continued to be used for approximately 100 years after the end of the Amarna Period. The Letters were written in the Akkadian language which helped facilitate foreign correspondence by filtering out inappropriate language. This aided the relative peace of the time. The letters present the earliest examples of international diplomacy, while their most common subjects are negotiations of diplomatic marriage, friendship statements, and exchanged materials.

Ancient Assyrian diplomacy

As the Egyptian and the Hittite empires weakened, the Assyrian state emerged and reached its zenith during the era of the Sargonid Dynasty (18th century BC), and the reigns of Sargon, Sennacherib, and Ashurbanipal. The Assyrian state tried to extend its control over the historical Fertile Crescent. They were particularly interested in gaining control over the key trade routes. The powerful Assyrian neighbours were forced to form coalitions and alliances in order to counterbalance this emerging Assyrian power. Assyrian dynasties used both war and diplomacy in order to achieve their goals.

The main Assyrian archaeological source is the Library of Ashurbanipal which was discovered during the excavations of the imperial palaces in Nineveh and Kuyunjik. The Library, consisting of clay tablets, is a rich source of materials, covering facets of both social and official Assyrian life, including diplomacy and communication. More specific details about their communication systems were also discovered, including the existence of a beacon scheme (an early telegraph system), which seems to have been used for transmitting messages.

Ancient Persian diplomacy

The Persian Empire was hegemonic, relying more on military might than on diplomatic skills. Limited forms of diplomatic interaction were developed with the city-states of ancient Greece. One of the main legacies of the Persian era was a highly developed communication system, i.e. an ancient-era internet.

The Greek historian Xenophon described the Persian messaging system during the rule of King Cyrus the Great (599 BC to 530 BC) as follows:

We have observed still another device of Cyrus' for coping with the magnitude of his empire; by means of this institution he would speedily discover the condition of affairs, no matter how far distant they might be from him: he experimented to find out how great a distance a horse could cover in a day when ridden hard, but so as not to break down, and then he erected post-stations at just such distances and equipped them with horses, and men to take care of them; at each one of the stations he had the proper official appointed to receive the letters that were delivered and to forward them on, to take in the exhausted horses and riders and send on fresh ones. They say, moreover, that sometimes this express does not stop all night, but the night-messengers succeed the day messengers in relays, and when this is the case, this express, some say, gets over the ground faster than the cranes.

Although the messenger system was developed for military purposes, it began to be used for receiving and sending envoys to neighbouring states and tribes. The Persian Empire discovered the potential of diplomacy in the last days of its existence when Darius III offered peace to Alexander of Macedonia based on ‘ancient friendship and alliance’. The refusal of this offer led to the conquering of the Persian Empire by the Greeks and the end of the period of ancient civilisations.

Ancient Chinese diplomacy

The first records of Chinese diplomacy date from the 1st millennium BC. By the 8th century BC, the Chinese had leagues, missions, and an organised system of polite dialogue between their many feuding Chinese kingdoms, including resident envoys who served as hostages to the good behaviour of those who sent them. The sophistication of this tradition, which emphasised the practical virtues of ethical behaviour in relations between states (no doubt in reaction to actual amorality), is well documented in the Chinese classics. Its essence is perhaps best captured by the advice of Zhuangzi to ‘diplomats’ at the beginning of the 3rd century BC. Zhuangzi advised them that:

If relations between states are close, they may establish mutual trust through daily interaction; but if relations are distant, mutual confidence can only be established by exchanges of messages. Messages must be conveyed by messengers [diplomats]. Their contents may be either pleasing to both sides or likely to engender anger between them. Faithfully conveying such messages is the most difficult task under the heavens, for if the words are such as to evoke a positive response on both sides, there will be the temptation to exaggerate them with flattery and, if they are unpleasant, there will be a tendency to make them even more biting. In either case, the truth will be lost. If truth is lost, mutual trust will also be lost. If mutual trust is lost, the messenger himself may be imperiled. Therefore, I say to you that it is a wise rule: “always to speak the truth and never to embellish it. In this way, you will avoid much harm to yourselves.

Chinese philosophers thought that the best way for a state to exercise influence abroad was to develop a moral society worthy of emulation by admiring foreigners, and to wait confidently for them to come to China to learn.

Ancient Indian diplomacy

Arthashastra, one of the oldest books in secular Sanskrit literature written by Kautilya, keeps the record of the diplomatic tradition of ancient India. The ruthless state system graded state power based on five factors, and emphasised espionage, diplomatic maneuver, and contention by 12 categories of states within a complex geopolitical matrix. It also proposed 4 means of statecraft (conciliation, seduction, subversion, and coercion) and 6 forms of state policy (peace, war, nonalignment, alliances, shows of force, and double-dealing).

Ancient India fielded three categories of diplomats: plenipotentiaries, envoys entrusted with a single issue or mission, and royal messengers; and two kinds of spies (those charged with the collection of intelligence and those entrusted with subversion and other forms of covert action).

Arthashastra also describes the detailed rules that regulate diplomatic immunities and privileges, the inauguration and termination of diplomatic missions, and the selection and duties of envoys. Thus, Kautilya describes the ‘duties of an envoy’ as:

Sending information to his king, ensuring maintenance of the terms of a treaty, upholding his king’s honour, acquiring allies, instigating dissension among the friends of his enemy, conveying secret agents and troops [into enemy territory], suborning the kinsmen of the enemy to his own king’s side, acquiring clandestinely gems and other valuable material for his own king, ascertaining secret information and showing valour in liberating hostages [held by the enemy].

Kautilya further stipulates that no envoys should ever be harmed, and should not be detained even when they deliver an ‘unpleasant’ message.

The Indian subcontinent, isolated from its neighbours by deserts, seas, and the Himalayas, had very little political connections to the affairs of other regions of the world until Alexander the Great conquered its northern regions in 326 BC. Later on, the establishment of the native Mauryan Empire opened the way for a new era in Indian diplomatic history. The Mauryan emperor Ashoka received a few emissaries from Macedonian kingdoms.

Except in South India, where the Chola dynasty and other kingdoms continued diplomatic and cultural exchanges with Southeast Asia and China, and preserved the text and memories of the Arthashastra, India’s distinctive mode of diplomatic reasoning and early traditions were forgotten and replaced by those of its Muslim and British conquerors.

The history of drinks: Beer

Although wine was consumed in Mesopotamia, it never reached the level of popularity that beer maintained for thousands of years. The Sumerian proverb says: 'He who does not know beer, does not know good.' Hymn to Ninkasi describes, in poetic terms, the step-by-step process of Sumerian beer brewing. Thus, we have the first written beer recipe, dating back to 1800 BC.

Beer became popular, not only because of the taste and its effects but because it was healthier to drink than the water of the region. The Babylonians had some 70 varieties, and beer was enjoyed by both gods and humans.

Beer was brewed by women, at home, as a supplement to meals. It was a thick drink, made from barley, and had to be consumed through a straw to avoid barley hulls. Once it developed into a commercial enterprise, the business was taken over by men who recognised how lucrative it could be. This led to the development of large-scale breweries. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the hero, distraught over the death of his friend, meets a barmaid who suggests that he should relax and have beer.

Egyptians loved their beer as much as the Mesopotamians, and breweries were built all around Egypt. The goddess Hathor was known as the mistress of drunkenness, which increased the goddess's popularity.

You can reference this text as

Jovan Kurbalija, Ancient Diplomacy: What can it teach us?, 'Diplomacy and Technology: A historical journey', 2021, DiploFoundation

Ancient world timeline

[Podcast] The history of drinks and diplomacy: An interview with Tom Standage

As part of the series of online discussions titled History of Diplomacy and Technology, Dr Jovan Kurbalija interviewed journalist and author Tom Standage to find out more about the influence that drinks had on ancient societies and diplomacy. From beer, wine, and rum, to tea and coffee, drinks have lubricated talks during diplomatic gatherings.

Standage is deputy editor of The Economist and is responsible for the newspaper’s digital strategy and the development of new digital products. He is the author of six history books, including Writing on the Wall: Social Media — The First 2,000 Years, the New York Times bestseller A History of the World in 6 Glasses (2005), and The Victorian Internet (1998) on the history of the telegraph.

Listen to the podcast or watch the recording of our March Masterclass Ancient Diplomacy: What can it teach us?

Recordings from all sessions are available on our YouTube channel.

[Podcast]

[Recording]

For more information on this topic, you can consult the following resources:

Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia

Author: Bertman, S. Oxford University Press, 2005

Modern-day archaeological discoveries in the Near East continue to illuminate our understanding of the ancient world, including the many contributions made by the people of Mesopotamia to literature, art, government, and urban life. The Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia describes the culture, history, and people of this land, as well as their struggle for survival and happiness, from about 3500 to 500 BCE.

Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia

Author: Black, J & Green, University of Texas Press, 1992.

Ancient Mesopotamia was a rich, varied and highly complex culture whose achievements included the invention of writing and the development of sophisticated urban society. This book offers an introductory guide to the beliefs and customs of the ancient Mesopotamians, as revealed in their art and their writings between about 3000 B.C. and the advent of the Christian era. Gods, goddesses, demons, monsters, magic, myths, religious symbolism, ritual, and the spiritual world are all discussed in alphabetical entries ranging from short accounts to extended essays.

The Literature of Ancient Sumer

Author: Black, J. et. al., Oxford University Press, 2006.

This anthology of Sumerian literature constitutes the most comprehensive collection ever published, and includes examples of most of the different types of composition written in the language, from narrative myths and lyrical hymns to proverbs and love poetry.

Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia

Author: Botteéro, J., Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, based on articles originally published in L'Histoire by Jean Bottéro, André Finet, Bertrand Lafont, and Georges Roux, presents new discoveries about this amazing Mesopotamian culture made during the past ten years. Features of everyday Mesopotamian life highlight the new sections of this book.

The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character

Author: Kramer, S. N., University of Chicago Press, 1971.

The Sumerians, the pragmatic and gifted people who preceded the Semites in the land first known as Sumer and later as Babylonia, created what was probably the first high civilisation in the history of man, spanning the fifth to the second millenniums B.C. This book is an unparalleled compendium of what is known about them.

Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization

Author: Kriwaczek, P., St. Martin's Griffin, 2012.

In Babylon, Paul Kriwaczek tells the story of Mesopotamia from the earliest settlements seven thousand years ago to the eclipse of Babylon in the sixth century BCE. Bringing the people of this land to life in vibrant detail, the author chronicles the rise and fall of power during this period and explores the political and social systems, as well as the technical and cultural innovations, which made this land extraordinary. At the heart of this book is the story of Babylon, which rose to prominence under the Amorite king Hammurabi from about 1800 BCE. Even as Babylon's fortunes waxed and waned, it never lost its allure as the ancient world's greatest city.

The A to Z of Mesopotamia

Author: Leick, G., Scarecrow Press, 2010

The A to Z of Mesopotamia defines concepts, customs, and notions peculiar to the civilization of ancient Mesopotamia, from adult adoption to ziggurats. This is accomplished through a chronology, an introductory essay, a bibliography, appendixes, and hundreds of cross-reference dictionary entries on religion, economy, society, geography, and important kings and rulers.

The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe

Author: Nelson, M., Routledge, 2005.

Comprehensive and detailed, this is the first ever study of ancient beer and its distilling, consumption and characteristics. Examining evidence from Greek and Latin authors from 700 BC to AD 900, the book demonstrates the important technological as well as ideological contributions the Europeans made to beer throughout the ages.

The Ancient Orient

Author: Von Soden, W., Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994.

This book represents the first comprehensive, interdisciplinary presentation of ancient Near Eastern civilization. Concentrating on Mesopotamia and North Syria and focusing particularly on the cultures of Sumer, Babylonia, and Assyria, von Soden covers the earliest times to Hellenization. His study of ancient "humanity in its wholeness" includes treatments of the history of language and systems of writing, the state and society, nutrition and agriculture, artisanry, economics, law, science, religion and magic, art, music, and more.

A History of the World in 6 glasses

Author: Standage T., Bloomsbury, 2006.

A History of the World in 6 Glasses tells the story of humanity from the Stone Age to the 21st century through the lens of beer, wine, spirits, coffee, tea, and cola. For Tom Standage, each drink is a kind of technology, a catalyst for advancing culture by which he demonstrates the intricate interplay of different civilisations.

The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt

Author: Wilkinson, R. H., Thames & Hudson, 2016.

Worshipped for over three-fifths of recorded history, Egypt’s gods and goddesses are among the most fascinating of human civilisation. The lives of pharaohs and commoners alike were dominated by the need to honor, worship, and pacify the huge pantheon of deities. The richness and complexity of their mythology is reflected in countless tributes throughout Egypt, from lavish tomb paintings and imposing temple reliefs to humble household shrines.

The History of the Ancient World

Author: Wise Bauer, S., W. W. Norton & Company, 2007.

A lively and engaging narrative history showing the common threads in the cultures that gave birth to our own. This is the first volume in a bold new series that tells the stories of all peoples, connecting historical events from Europe to the Middle East to the far coast of China, while still giving weight to the characteristics of each country. The author provides both sweeping scope and vivid attention to the individual lives that give flesh to abstract assertions about human history.