Reforms to the International Financial Architecture | Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 6

Introduction

CHAPEAU

The challenges that we are facing can be addressed only through stronger international cooperation. The Summit of the Future, to be held in 2024, is an opportunity to agree on multilateral solutions for a better tomorrow, strengthening global governance for both present and future generations (General Assembly resolution 76/307). In my capacity as Secretary-General, I have been invited to provide inputs to the preparations for the Summit in the form of action-oriented recommendations, building on the proposals contained in my report entitled “Our Common Agenda” (A/75/982), which was itself a response to the declaration on the commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the United Nations (General Assembly resolution 75/1). The present policy brief is one such input. It elaborates on the ideas first proposed in Our Common Agenda, taking into account subsequent guidance from Member States and over one year of intergovernmental and multi-stakeholder consultations, and rooted in the purposes and the principles of the Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international instruments.

PURPOSE OF THIS POLICY BRIEF

The international financial architecture, crafted in 1945 after the Second World War, is undergoing a stress test of historic proportions – and it is failing the test. Designed by and for the industrialized countries of the post-war period, at a time when neither climate risks nor social inequalities, including gender inequality, were considered pre-eminent development challenges, the international financial architecture already had structural deficiencies at the time of its conception. These have become increasingly at odds with the reality and needs of the world today, making the international financial architecture entirely unfit for purpose in a world characterized by unrelenting climate change, increasing systemic risks, extreme inequality, entrenched gender bias, highly integrated financial markets vulnerable to cross-border contagion, and dramatic demographic, technological, economic and geopolitical changes.

The existing architecture has been unable to support the mobilization of stable and long-term financing at scale for investments needed to combat the climate crisis and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals for the 8 billion people in the world today. It is plagued with inequities, gaps and inefficiencies that are deeply rooted in the system, including:

- Higher borrowing costs for developing countries in financial markets, even after taking into account default risk and market volatility; many governments dedicate a high share of revenue to debt service payments while being unable to sufficiently invest in the delivery of fundamental rights in health, education and social protection;

- Vast variation in countries’ access to liquidity in times of crisis, with only a small share of special drawing rights (SDRs) allocated to developing countries; for example, the continent of Africa, home to 1.4 billion people and more than 60 per cent of the world’s extreme poor, received only 5.2 per cent of the latest issuance of SDRs;

- Dramatic underinvestment in global public goods, including pandemic preparedness and climate action;

- Volatile financial markets and capital flows, repeated global financial crises and recurring sovereign debt distress, with dire consequences for sustainable development.

Similarly, the international tax architecture has not kept pace with a changing world. While countries ultimately need to rely on national resources to finance investment in their sustainable and equitable development, global tax evasion and avoidance restricts their ability to do so.

A two-track world of haves and have-nots holds clear and obvious dangers for the global economy and beyond. Without urgent, ambitious action to change course, this gap will translate into a lasting divergence, economic fragmentation and geopolitical fractures. It is in the interest of all developed and developing countries to reform the international financial architecture in order to rebuild trust in the system and prevent a further drifting apart and eventual fragmentation of international financial and economic relations. We must craft a new set of rules and institutions that support convergence for the twenty-first century and enable all countries to achieve sustainable, inclusive and just transformations. The international financial architecture should be structured to proactively support the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals and the realization of human rights. The only way to facilitate such a structure is through ambitious reform, starting with more inclusive, representative and, ultimately, more effective global economic governance.

The present policy brief sets out action-oriented recommendations for reforming the international financial and tax architecture in six areas:

- Global economic governance;

- Debt relief and the cost of sovereign borrowing;

- International public finance;

- The global financial safety net;

- Policy and regulatory frameworks that address short-termism in capital markets, better link private sector profitability with sustainable development and the Sustainable Development Goals, and address financial integrity;

- Global tax architecture for equitable and inclusive sustainable development.

What is the international financial architecture?

The international financial architecture refers to the governance arrangements that safeguard the stability and function of the global monetary and financial systems. It has evolved over time, often in an ad hoc fashion, driven by the policy preferences of large economies in response to economic and financial shocks and crises. The term “non-system”1See, for example, José Antonio Ocampo, Resetting the International Monetary (Non)System (Oxford University Press, 2017). has sometimes been used to describe the existing set of international financial frameworks, rules, institutions and markets that together make up the international financial architecture. The international financial architecture includes:

- Governance of public international financial institutions, such as the multilateral development banks and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as well as other international public development banks and global funds (such as the Green Climate Fund);

- Financial standard-setters that establish norms for the governance of private finance, such as the Financial Stability Board, the Bank for International Settlements, the International Organization of Securities Commissions, the International Accounting Standards Board and the Financial Action Task Force;

- Monetary arrangements, such as regional financial arrangements and the network of bilateral swap lines;

- Informal country groupings that act as norm-setters, such as the Group of Seven (G7) and Group of 20 (G20);

- Formal but non-universal norm-setting bodies, in particular the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD);

- Creditor groups that address sovereign debt issues, including the Paris Club, the London Club, the Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the Debt Service Suspension Initiative, agreed by G20 and Paris Club countries, and the International Capital Market Association (a private entity that publishes model clauses for debt instruments), as well as global credit rating agencies;

- United Nations as a norm-setter and implementer.

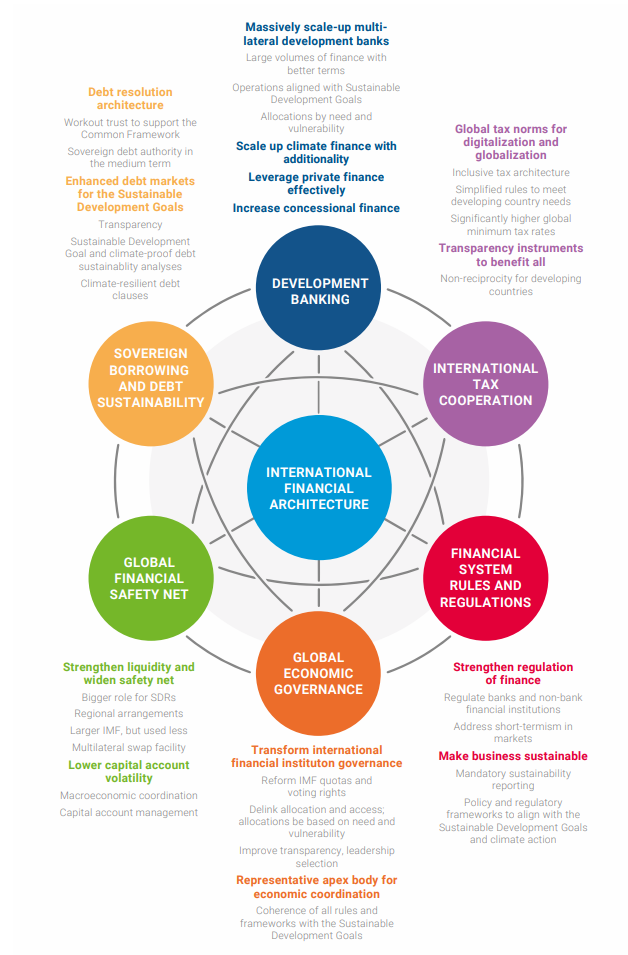

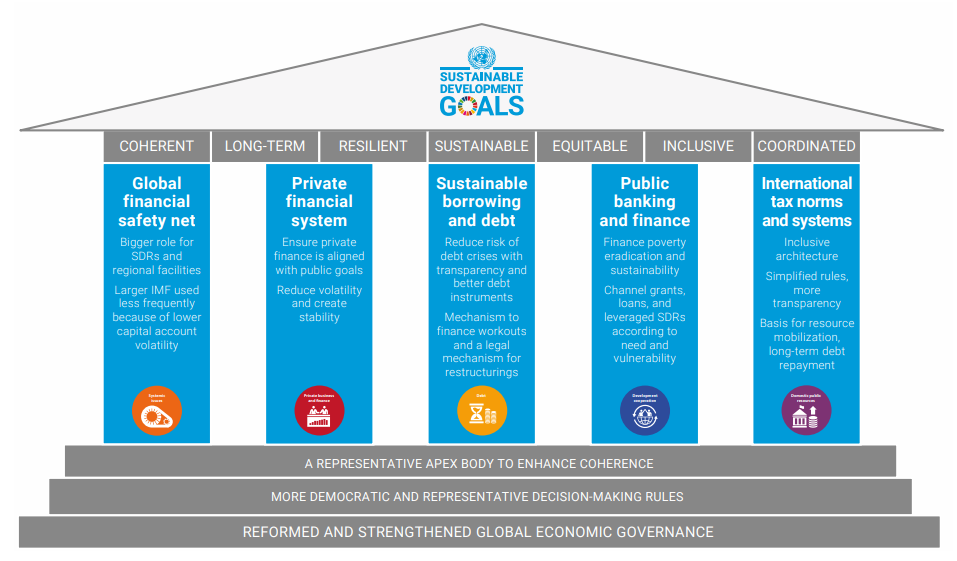

While the international financial architecture does not include all the action areas of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, it needs to be coherent with and complemented by rules governing trade, tax, financial integrity, technology, environmental sustainability and climate action, as well as other development issues. Reforms to the international architecture (see figure I) will have the greatest impact if accompanied by strengthened national financing policies and capacities, for example through integrated national financing frameworks, which will require significant capacity-building with support from the international community.

Reform and strengthen global economic governance

THE CASE FOR REFORM

Global economic governance has not kept pace with changes in the global economy, the rise of the global South and other geopolitical changes (including the end of colonialism and the recognition of the human right to self-determination). The current arrangement and governance of international financial institutions was created almost 80 years ago at a United Nations conference with only 44 delegations present (compared with the 190 members of IMF and the World

Bank today). Despite repeated commitments to meaningfully adapting the system, and notwithstanding some improvement between 2005 and 2015, the representation of developing countries in international financial institutions, regional development banks and standard-setting bodies has remained largely unchanged in recent years. The Governments of the largest developed countries continue to hold veto powers in the decision-making bodies of these institutions, and changes to voting rights at the international financial institutions are some of the most contested reforms in global governance.

FIGURE I

REFORMED INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL ARCHITECTURE THAT IS FIT FOR PURPOSE FOR THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

In addition, a lack of coherence and coordination in global economic management has resulted in disjointed responses to economic, financial, food, energy and related crises, as well as disaster and conflict-related emergencies. Shocks from financial and economic crises, conflict, natural disasters and disease outbreaks spread rapidly in our highly interconnected world. The end of the Bretton Woods system of exchange rates in the 1970s upended the coordination mechanisms that had been agreed in the 1940s, which were themselves unsatisfactory. That change has spawned a string of clubs and informal institutions (from the Groups of Five, Six, Seven, Eight and 10 and the Committee of Twenty to G20), as well as more formal institutions with varying configurations of membership (e.g. Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, International Organization of Securities Commissions, Financial Action Task Force, Financial Stability Board, International Monetary and Financial Committee and Development Committee), without effective representation of developing countries and with insufficient global coordination on economic and related issues.

ACTION 1: TRANSFORM THE GOVERNANCE OF INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS

- Update IMF quota formulas to reflect the changing global landscape.

- Reform voting rights and decision-making rules to make them more democratic, for example through a double majority rule.

- Delink access to resources from quotas, with access instead determined by both income and vulnerabilities (through a multi-vulnerability index or “beyond gross domestic product (GDP)” indicators).

- Boost the voice and representation of developing countries on boards and improve institutional transparency.

- Strive for gender-balanced representation in all the governance structures of these institutions, in particular at the leadership level.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND GOVERNANCE REFORM

The sixteenth general review of quotas at IMF, scheduled to conclude by mid-December 2023, is an opportunity to strengthen funding for IMF and expand its lending capacity while also strengthening the voice and representation of developing countries.

IMF quotas play several roles, including: specifying country contributions to the Fund’s core resources; determining the majority of voting rights; providing nominal ceilings on resource access, beyond which countries begin to pay higher charges and IMF programmes are subject to more political oversight; and determining member countries’ shares in SDR allocations. The formula used to guide IMF quota allocations, which was agreed in 2008 (50 per cent based on GDP, 30 per cent on trade openness, 15 per cent on capital flow volatility and 5 per cent on the levels of reserves), reflects these different uses by attempting to balance two potentially contradictory concepts – a country’s ability to pay and the likelihood that it will need resources.2In addition, reliance on trade data as a proxy for a country’s openness is not as relevant in a highly globalized and financialized economic system, as few balance of payments crises are generated by sustained trade deficits given the outsized role of capital flows

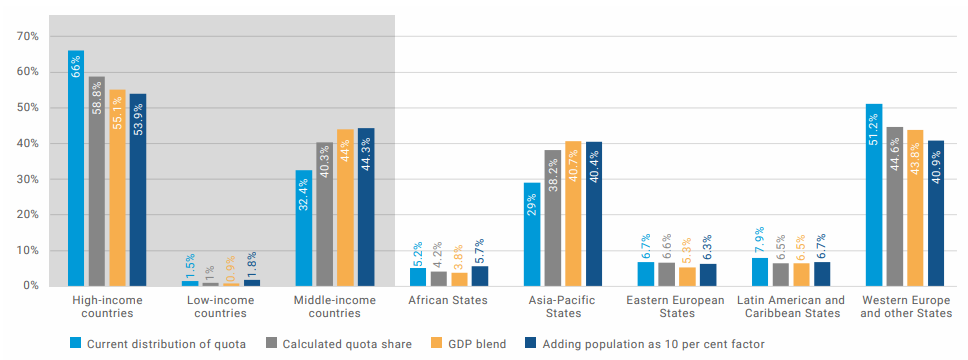

IMF member countries should separate the ability to pay from voting rights and allocations and develop different instruments for different uses. First, the process for determining contributions on the basis of ability to pay should be straightforward and based on national income, with appropriate adjustments and limitations, as is regularly accomplished at the United Nations (see figure II for a comparison of various quota formulas.) The contribution formula should also automatically adjust the overall quota size to reflect developments over time, without being held up by multi-year political negotiations.

Second, decisions at IMF should be agreed through a double majority decision-making rule, similar to voting rules in many legislatures. The value of ensuring widespread agreement on reform is already recognized in the Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund, amendments to which require a double super majority (85 per cent of voting rights, 60 per cent of member countries). Double majority decision-making should be used for IMF decisions. This approach will provide additional incentive for consensus-based decision-making and strengthen trust in the institution.

Voting rights are currently a combination of quotas and basic votes, which are given to all countries equally. However, basic votes have fallen to 5.5 per cent of the total voting rights – less than half of the level at the founding of IMF. At a minimum, the share of basic votes should be returned to the original level of one ninth of total voting rights. One proposal for the remaining eight ninths is to add a population component to the quota formula (see figure II). However, changing the decision rules to double majority voting makes the distribution of quotas on their own less important in this area.

Third, limits on access to IMF borrowing and allocations of special drawing rights should be delinked from quotas, so that both can operate more effectively. In accordance with ongoing discussions at the United Nations, needs assessments should be linked to income and vulnerability (through a multidimensional vulnerability index or “beyond GDP” indicators).

FIGURE II

MODELS OF INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND QUOTA DISTRIBUTION

Note: International Monetary Fund (IMF) quotas are the building blocks of the Fund’s financial and governance structure, setting contributions, access limits and almost 95 per cent of voting rights. Countries are categorized by World Bank income group and United Nations political grouping. “Calculated quota share” shows the expected quota distribution if the agreed quota formula were implemented as specified by the IMF Executive Board and using 2021 data for gross domestic product (GDP), current account balances and reserves. “GDP blend” reflects one element of the agreed IMF quota formula, with country GDP shares calculated with 60 per cent weight on GDP measures with market exchange rates and 40 per cent weight on GDP measures by purchasing power parity. “Adding population as 10 per cent factor” simulates adding population to the current formula as a factor with a 10 per cent weight and reducing the weight of the openness factor to 25 per cent and the weight of the variability factor to 10 per cent, while retaining other factors and compression

WORLD BANK GOVERNANCE REFORM

Historically, the World Bank and IMF governance reforms were often aligned, until the annual meeting of IMF and the World Bank Group held in Lima in 2015. At that meeting, the World Bank shareholders agreed on the Lima shareholding principles, which included a dynamic formula to guide shareholding reviews. The dynamic formula is a good measure of ability to contribute but it has not been effectively implemented. In the Bank’s assessment, 43 countries remain underrepresented, with 10 extreme outliers.

Capital increases at the multilateral development banks, needed to enhance the provision of low-cost development finance, present an opportunity to increase the voting shares of developing countries. Capital increases should be used to fully implement the agreed dynamic formula so that selective capital increases are a core element of boosting the Bank capital. The Board of the World Bank should also develop procedures to implement double majority decision-making.

ADDITIONAL REFORMS

Additional reforms to governance at international financial institutions are important to balance the reform agenda. The current board structure is less representative than the original planned structure. The original board included 12 directors for 44 member countries. Today, 24 and 25 board members represent the 190 member countries of IMF and the World Bank, respectively. To maintain the original ratio of board members to member countries, the board should have approximately 52 members. The Boards face a trade-off between efficiency and representation, but an expansion of the boards to allow more voices at the table can easily be accommodated. Transparency and accountability should be considered cornerstones of modern institutions. Decision-making processes at public institutions should be conducted transparently and decisions should be based on material that is in the public domain to build trust in the multilateral system.

Lastly, the plethora of other standard setting institutions (e.g. Bank for International Settlements, Financial Stability Board, etc.) must also rebalance their governance to enhance legitimacy and to ensure that universality and inclusion do not remain sticking points in finance, tax and anti-money-laundering governance.

ACTION 2: CREATE A REPRESENTATIVE APEX BODY TO SYSTEMATICALLY ENHANCE COHERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM

Member States should use the opportunity presented by the Summit of the Future to agree on a coordinating body on economic decisions in the form of a Biennial Summit, at the level of Heads of State and Government, between members of G20 and of the Economic and Social Council, the Secretary-General and the heads of the international financial institutions, to work towards a more sustainable, inclusive and resilient global economy.

As noted in Our Common Agenda, a coordinating body through the Biennial Summit, building on the spirit of earlier proposals for an “Economic Security Council”, would be a natural venue to address immediate issues, including the promotion of ultra-long-term financing for sustainable development and a Sustainable Development Goal stimulus for all countries in need, and longer-term issues, such as making the international financial architecture fit for purpose and resilient to global crises, including food, energy and financial crises. The Biennial Summit could also function as a forum to address incoherence in the rules governing trade, aid, debt, tax, finance, environmental sustainability and climate action, and other development issues. In addition, it should help to reduce or discontinue informal groupings.

Lower the cost of sovereign borrowing and create a lasting solution for countries facing debt distress

THE CASE FOR REFORM

Sovereign borrowing allows countries to invest in the future. Productive investments, including in resilient infrastructure, can improve debt sustainability in the long run: a growing economy helps to raise domestic tax revenue and the capacity to service debt over time. Debt financing is also critical to the financing of crisis responses. Such positive outcomes are, however, only achievable if borrowing and lending decisions are made responsibly, resources are used effectively, risks are well managed and lending is affordable. Even then, well-managed debt can become unsustainable owing to external shocks, such as disasters, pandemics and global financial and liquidity crises, which can raise the cost of debt refinancing to unsustainable levels.

Today, debt has once again reached critical levels in many countries. While sovereign debt had been rising steadily over the past decade, the confluence of global shocks since 2020 pushed many countries over the edge: 9 least developed countries and other low-income countries are currently in debt distress, and another 27 are at high risk.3Assessment of external debt distress ratings for least developed countries and other low-income countries using the IMF/World Bank Debt Sustainability Framework for Low-Income Countries, available at www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/dsa/dsalist.pdf. Almost 40 per cent of all developing countries (a total of 52 countries) suffer from severe debt problems and extremely expensive market-based financing.4Adding up all developing countries that have a credit rating of “substantial risk”, “extremely speculative” or “default”, a debt sustainability analysis risk rating of “in distress” or “at high risk of debt distress” and/or a bond spread of more than 1,000 basis points; see Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2023 (United Nations publication). While these countries account for only 2.5 per cent of the global economy, they are home to 15 per cent of the global population and 40 per cent of all people living in extreme poverty. They include more than half of the world’s 50 most climate-vulnerable countries.

Even for countries that are not at immediate risk of debt distress, high borrowing costs in capital markets can sharply curtail countries’ ability to invest in recovery and sustainable development. Debt has an impact on a country’s ability to reduce inequality and invest in climate, the environment and essential services, in accordance with its obligations under international legal frameworks for human rights, labour and the environment. For example, as of early 2023, sovereign bond yields for 14 countries were more than 10 percentage points above yields on bonds issued by the Treasury of the United States of America (US treasury bonds). For another 21 countries, sovereign bond yields were more than 6 percentage points above US treasury bond yields.5As at 13 January 2023 The high cost of borrowing not only inhibits investment in the Sustainable Development Goals but also raises the risk of future debt crises. Recent analysis has found that most countries that have had costly debt crises in the past would have been solvent had they enjoyed continuous access to financing at low rates (akin to the borrowing costs of rich countries).6Ugo Panizza, “Long-term debt sustainability in emerging market economies: a counterfactual analysis”, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies International Economics Department Working Paper Series, April 2022 (Working Paper No. HEIDWP07-2022).

Debt crisis prevention and the fair and effective resolution of sovereign debt crises when they do arise have been long-standing concerns of the international community. Debt sustainability is addressed in both the Monterrey Consensus of the International Conference on Financing for Development (2002) and the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (2015), in which it is noted that both debtors and creditors share responsibility for prevent- ing and resolving unsustainable debt situations.

To prevent debt crises from arising, principles for responsible borrowing and lending highlight three common areas: responsible spending and debt management by borrowers; transparency by both debtors and creditors; and due diligence and enhanced risk management by creditors. Credit rating agencies and IMF/World Bank debt sustainability analyses, which provide information and analysis to creditors, play an important role in this area.

When debt crises do occur, both the Monterrey Consensus and the Addis Ababa Action Agenda call for debt resolutions to be timely, orderly, effective, fair and negotiated in good faith. Yet, in the absence of a rules-based international architecture, debt resolution has typically been too little, too late. Restructurings are often not deep enough to provide a clean slate and avoid repeat crises, and often materialize too late, with protracted crises and high social costs. Today’s more complex debt landscape has only exacerbated this challenge.

In response to the latest crises, the international community has taken steps to enhance the global sovereign debt architecture – principally, the establishment of the Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the Debt Service Suspension Initiative, in which Paris Club and G20 bilateral creditors agreed for the first time to coordinate and cooperate on debt treatment. However, these steps have not had the desired results. Implementation of the Common Framework has been extremely slow because of continued creditor coordination challenges, undermining confidence and limiting uptake. Middle-income countries in distress are not eligible, with high-profile restructurings outside the Common Framework marred by similar delays, causing protracted debt crises that dramatically set back development progress.

Repeat cycles of sovereign debt distress throughout history underline the need for a more effective sovereign debt architecture to help to prevent debt crises, support the provision of affordable financing for investment in the Goals and facilitate more effective and fair restructurings when needed. The Sustainable Development Goals stimulus called for an improved multilateral debt relief solution. The present policy brief sets out concrete recommendations for that proposal and for long-term structural solutions, including: (a) creating sovereign debt markets that support the achievement of the Goals and (b) a two-step process for facilitating sovereign debt resolutions that are effective, efficient and equitable.

ACTION 3: REDUCE DEBT RISKS AND ENHANCE SOVEREIGN DEBT MARKETS TO SUPPORT SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS

- Update principles of responsible borrowing and lending to reflect the changing global environment and the human rights obligations of States.

- Increase debt management and transparency.

- Improve debt sustainability analysis and credit ratings.

- Improve debt contracts, including by incorporating State-contingent clauses.

First, the international community should fulfil the long-standing commitment to work towards a global consensus on guidelines for sovereign debtor and creditor responsibilities. As noted in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, this effort can build on existing initiatives by bringing together existing principles of responsible borrowing and lending and updating them to incorporate the Sustainable Development Goals and reflect the changing global environment.

Second, debt management should be improved, including through capacity development, and debt transparency should be enhanced. To support transparency, the international community should develop and host a publicly accessible registry of debt data for developing countries, to strengthen and coordinate existing data collection initiatives. To incentivize uptake and maintenance, multilateral development banks could introduce incentives in their operations, and both creditor and debtor countries could adopt supporting legislation or regulations.

Third, debt sustainability analysis and credit ratings, including their methodologies, should be made publicly available in a more timely and routine manner and strengthened and updated to reflect changing sovereign debt markets with a view to supporting the Sustainable Development Goals, including by distinguishing between liquidity and solvency crises; developing long-term debt sustainability analyses; and incorporating into debt sustainability analyses fiscal space for investments in climate and the Goals.

Existing debt sustainability analyses and ratings generally focus on near-term financial risks. When interest rates spike during a liquidity crisis, many countries – even some that were considered solvent when credit spreads were lower – are deemed to be at high risk of default, pushing borrowing costs even higher and creating a vicious cycle. “Solvency” debt sustainability analyses would clearly distinguish between liquidity crises (when long-term affordable financing can be the solution) and solvency crises (when debt write-downs may be needed), which is especially important in the context of scaling up official lending as part of the Sustainable Development Goals stimulus. A simple proxy to calculate “solvency” in such debt sustainability analyses would be to run existing models using multilateral development bank borrowing rates rather than market rates (which are higher) for refinancing costs. Comparing the “solvency” outcome to traditional debt sustainability analyses would highlight when a country would be fundamentally solvent if it had access to improved financing terms. Publishing these results compared to traditional debt sustainability analyses in a systematic and transparent manner would provide valuable information to markets, potentially lowering the cost of borrowing for countries not facing solvency crises.

Long-term debt sustainability analyses should also incorporate both climate risks and the impacts of investment in long-run projections, to gauge the positive effects of investment in productivity and resilience on debt sustainability. Furthermore, reviews of debt sustainability assessments should better reflect a country’s Sustainable Development Goal financing needs by incorporating fiscal space for investments in the Goals (in essence changing from a system of seniority that prioritizes payments to external creditors to a system in which seniority is given to social protection obligations and payments related to other domestic needs). Although this change would have the effect of increasing the estimated risk of default, it would more accurately reflect how much of a write-down is necessary when defaults do occur.

Complementary reforms are needed in credit assessments by private credit rating agencies. The international community should regularly review and update the transparency of sovereign rating methodologies and should continue to reduce reliance on credit ratings in regulations, building on the peer review published in 2014 by the Financial Stability Board on its principles for reducing reliance on credit rating agency ratings. Credit rating agencies should also publish longer-term ratings and clearly distinguish between the model-based and discretionary components of sovereign ratings to help investors to better assess the objectivity of ratings. In parallel, public institutions should transparently publish comparable debt sustainability analyses for all sovereign issuers, which investors could then use as a benchmark to distinguish between model-based ratings and the judgments of credit rating agencies.7See Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “Credit rating agencies and sovereign debt: four proposals to support achievement of the SDGs”, Policy Brief No. 131 (March 2022).

Fourth, debt contracts should be improved. Financial instruments that tie debt service to economic conditions and non-economic shocks could reduce the likelihood of future crises. Lenders should consistently include force majeure clauses and State-contingent contractual clauses that automate debt service relief in the case of external shocks, such as disasters or pandemics. This effort should be led by official lending building on existing efforts (e.g. French Development Agency, Inter-American Development Bank and some export-import banks). Such clauses can be net-present-value neutral to have no or minimal pricing impact. However, they cannot address larger solvency problems, and countries may still require debt restructuring. For debt crisis resolution, it is also important to incorporate enhanced collective action clauses in bond contracts and majority voting provisions in loan agreements, along with additional measures discussed below.

In addition, the international community should promote the greater use of debt swaps for the Sustainable Development Goals and for the climate, in particular for climate change adaptation, with a focus on making debt more affordable and investing savings into climate resilience and the Goals, for example by developing a reference framework for debt swaps-for-Sustainable Development Goals.

ACTION 4: ENHANCE DEBT CRISIS RESOLUTION THROUGH A TWO-STEP PROCESS: A DEBT WORKOUT MECHANISM TO SUPPORT THE COMMON FRAMEWORK AND, IN THE MEDIUM TERM, A SOVEREIGN DEBT AUTHORITY

- Expand Common Framework eligibility to middle income countries that have significant official debt and require debt restructuring.

- Set up a debt workout mechanism, for example at a multilateral development bank, to address slow progress in the Common Framework due to creditor coordination challenges among and between official and commercial creditors.

- Create an inclusive and representative sovereign debt authority to develop and implement a multilateral legal framework for sovereign debt restructuring.

There is a need to urgently address well-recognized shortcomings of the Common Framework, including eligibility, timeliness and comparability of treatment, in a systematic manner. For example, the Common Framework does not have a mechanism to address comparability of treatment between and across creditor classes (official and private creditors). A debt workout mechanism should be put in place to address these issues. The Common Framework and the mechanism must also be accessible to middle-income countries that require debt relief.

The mechanism, which could be housed, for example, at a multilateral development bank, would aim to speed up Common Framework debt restructuring. Debt would be swapped to the mechanism, with debt treatment, still on a case-by-case basis, executed by an expert body.8Debtor countries would continue to approach the Common Framework for relief, but official bilateral debt deemed to be unsustainable would be swapped or sold to the debt workout mechanism, with creditors having agreed a priori to a set of rules. The mechanism could be funded by bilateral creditors (who are also the shareholders of the multilateral development bank housing the facility). Creditor countries could account for the swap as either financing for the mechanism or debt relief. The mechanism would negotiate debt treatment based on a set of predetermined principles, and aim to fulfil comparability of treatment across both official and commercial creditor groups. To do so, the mechanism could use sticks and carrots to enforce and incentivize private creditor participation in restructurings for comparable treatment with official creditors.9This could include penalizing hold-outs, which could be supported by legal measures in major financial jurisdictions to limit the leverage of hold-out creditors, as well as credit enhancements. Ultimately, the mechanism could act as an impartial adviser and “honest broker” in debtor/creditor negotiations, either directly or through a system of independent panels of experts, which could be responsible for mediating the negotiation between the debtor and its commercial creditors.

A much-strengthened Common Framework should be complemented by an inclusive and representative sovereign debt authority independent of creditor and debtor interests, to ensure timely, orderly, effective and fair debt resolutions in an increasingly complex debt landscape. For the same reason that formal bankruptcy regimes – not voluntary processes – resolve corporate insolvencies, an efficient sovereign insolvency system will ultimately be required to backstop and facilitate sovereign defaults. The absence of such a rules-based system creates inefficiencies (restructurings that are too little too late) with high social costs, and uncertainty in markets that contribute to high risk premia. A lack of a bankruptcy procedure strengthens the hand of hold-out creditors and disadvantages other claimants on the sovereign resources, such as pensioners and workers.

A sovereign debt authority should address these and other shortcomings in the current “non- regime”. It should build on existing principles, including General Assembly resolution 69/319, entitled “Basic Principles on Sovereign Debt Restructuring Processes”, adopted in 2015. It would work in conjunction with the proposed debt workout mechanism. For example, the mechanism (or its arbitration panel) could first seek to facilitate voluntary debtor/creditor negotiations, after which it would refer the case to a legal mechanism under a sovereign debt authority. Such an approach was endorsed in 2009 by the Commission of Experts on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System convened by the President of the General Assembly (the Stiglitz Commission).

Massively scale up development and climate financing

THE CASE FOR REFORM

As highlighted in the Sustainable Development Goals stimulus, the international system must scale up both concessional and non-concessional affordable and long-term financing for the Goals and climate action. Public development banks are uniquely positioned to take more risk, lower the cost of capital and accelerate investment in the Goals. Lending by multilateral development banks must be long-term, and the terms and conditions should set a cost of borrowing – both concessional and non-concessional – that is below market rates.

The way in which the multilateral development bank system uses its capital and spends resources is currently under discussion. India, as the President of G20 for 2023, has suggested a strong focus on multilateral development bank reforms, and the World Bank itself has drawn up an “evolution road map”. Lending by multilateral development banks is low by historical standards, as shareholders have not increased the size of the banks’ paid-in capital bases in line with the increase in size of the global economy or sustainable development investment needs.

In addition, amounts mobilized from the private sector by official development finance total between $45 billion and $55 billion per year, overwhelmingly in middle-income countries. This falls well short of the call by the World Bank in 2015 for financing “from billions to trillions”, raising questions as to the effectiveness of the current model for leveraging private finance. We need to move with more ambition to “crowd in” private sector financing and move swiftly with policy de-risking (building domestic enabling environments for sustainable development investment, preparing pipelines, strengthening capacity-building), as well as develop new frameworks for financial risk-sharing, including by multilateral development banks.

Multilateral development banks are not yet exploring how to effectively leverage their combined balance sheet, which could further increase lending without any impact on their credit ratings. Given the geographic concentration of regional development banks, there is scope to diversify risk across the multilateral development bank system, thus allowing for greater lending overall. Multilateral development banks should also work more closely with the broader system of public development banks, which has a large footprint, with 522 development banks and development finance institutions having total assets of $23 trillion.

Strengthening the role of multilateral development banks is, however, more than just about quantities. Multilateral development banks will need to change their business models to ensure that all lending has greater sustainable development impact. This includes reorienting the allocation of concessional finance to reflect today’s vulnerabilities, such as from climate disasters, and realigning internal incentives, and includes support for conflict-affected countries, including middle-income countries, where multilatera development banks have operational challenges beyond the need for tailored lending conditions and grants.

Reforms are also important in the context of climate finance. Climate funds under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement, such as the Green Climate Fund, must play a critical role of delivering to developing countries. However, many developing countries, especially small island developing States, still face significant obstacles in accessing such funds. There are currently around 73 public or partially public climate funds, with 62 multilateral funds disbursing only $3 billion to $4 billion in total in 2020. At present, they do not coordinate effectively. The funds under the umbrella of the Framework Convention are undercapitalized.

ACTION 5: MASSIVELY INCREASE DEVELOPMENT LENDING AND IMPROVE TERMS OF LENDING

- Multilateral development banks boost lending to 1 per cent of global GDP (by $500 billion–$1 trillion a year), supported by an increase in paid-in capital and more efficient use of their balance sheets.

- Offer ultra-long affordable financing, with State-contingent repayment clauses, and ease modalities of access to such financing.

- Increase local currency lending, while better managing risk through diversification.

Analysis in the Sustainable Development Goals stimulus shows that, with stronger capital bases, the addition of other resources and more efficient use of existing paid-in and callable capital, multilateral development banks can increase lending by at least $500 billion per year, aiming for $1 trillion. That represents just 0.1 to 0.2 per cent of total global financial assets to be invested in reducing poverty, hunger, inequalities, including gender inequality, and climate change. To further support lending, multilateral development banks should also build on the solution developed by the African Development Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank to set up facilities to rechannel SDRs, while each Member State with unused SDRs should provide at least half of those to be rechannelled through facilities at multilateral development banks.

Multilateral development banks should offer affordable ultra-long-term loans, with repayment terms of 30 to 50 years. Incorporating State- contingent repayment clauses into loan contracts can automate standstills for countries hit by predefined shocks, such as climate-related disasters. These can be net present value neutral, so as not to affect the credit ratings of multilateral development banks.

Increasing local currency lending is critical to reducing the currency risks faced by Governments. International financial institutions are better placed than sovereigns to manage currency risk, since they can diversify across currencies, while sovereigns face a concentrated foreign exchange risk. Increased local currency lending should also go hand in hand with greater use of diversification in risk management, as called for in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, including by better leveraging the system of multilateral development banks (see action 8). Local currency lending could also be funded by greater borrowing in domestic capital markets, which would have the additional benefit of helping to develop those markets. Nonetheless, local currency borrowing, like all debt, carries risks, which countries need to manage as part of a debt management strategy.

ACTION 6: CHANGE THE BUSINESS MODELS OF MULTILATERAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS AND OTHER PUBLIC DEVELOPMENT BANKS TO FOCUS ON SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOAL IMPACT; AND MORE EFFECTIVELY LEVERAGE PRIVATE FINANCE FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOAL IMPACT

- Update development bank missions, policy, practice, metrics and internal incentives to focus on Sustainable Development Goal impact and climate action, aligned with international human rights, labour, and environmental norms and standards.

- Phase out fossil fuel finance and adopt a stronger focus on advancing the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment.

- Develop new frameworks for when and how to scale up leveraging private finance to maximize sustainable development impact.

All lending by multilateral development banks and other public development banks must be fully aligned with sustainable development, including explicitly embracing the Sustainable Development Goals in development bank mandates. First, development banks should update internal metrics, incentives and lending decision-making to consider projects’ impacts, both positive and negative, on the Sustainable Development Goals as a core element throughout the decision-making process, complementing the current safeguards, which are often applied ex post facto. Development bank lending policy needs to have greater linkages to country plans. Loan origination can be drastically simplified, and resources disbursed faster, without compromising on loan quality, by front-loading work into creating sound national sustainable development plans accompanied by integrated national financial frameworks. When such country-owned planning tools are available, all multilateral development banks should align behind them. This can help to streamline and accelerate the lending process ex ante, which can be complemented by ex post incentives for borrowers to meet climate and Sustainable Development Goal targets.

Second, all public development banks should phase out fossil fuel finance and substantially increase the quality and quantity of finance for climate adaptation and resilience-building in vulnerable developing countries. This should include a strong focus on investing in the areas that remain essential to achieving just transitions for all, including in universal social protection and job creation in the green economy. It is essential that multilateral development banks advance the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment and mainstream climate action in all their work, including in their private sector financing arms, while avoiding diverting funds from the financing of sustainable development in developing countries. This is particularly important as mitigation financing has gone overwhelmingly to middle-income countries. Climate mitigation finance must be additional, for which bigger multilateral development bank balance sheets are essential. Better and more transparent accounting, including developing new ways to account for climate mitigation to ensure additionality, will also be essential.

Third, development banks should develop and transparently publish impact reporting, with internal incentives tied to maximizing Sustainable Development Goal impact, subject to risk and financial viability. This includes tracking and analysing data on the gender equality implications across all multilateral investments. In this way, they can be market leaders, setting a precedent for private investors.

Fourth, to increase leveraging of private finance, multilateral development banks and other development finance institutions need to rethink current modalities, in line with the principles of blended finance in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda. Blended finance should not be about searching for bankable projects; it should be about maximizing sustainable development impact, while understanding and pricing financial risks. For example, this could include: evaluating sustainable development investment needs based on a country’s sustainable development priorities, analysing the most appropriate financing structure to meet these needs (whether private, public or blended finance) and evaluating and pricing risks (potentially as part of integrated national financial frameworks), with the aim of maximizing the sustainable development impact per dollar spent. This is fundamentally different from the Maximizing Finance for Development approach of the World Bank.

In addition, multilateral development banks should design innovative instruments, such as sharing in equity upside, to ensure that the private partner is not overcompensated – a core principle of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda. Changing terminology from “de-risking” to “risk-sharing” could help to enforce the importance of the public partner properly evaluating and pricing risks. Funding arrangements that lower the cost of capital for developing countries, including to finance the climate transition, address macro risks (such as currency risk) instead of project-level risks. The reinsurance fund noted in action 8 could be used to insure, and properly price, risks that private investors may be uncomfortable in taking.

FIGURE III

IMPACT OF THE INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL ARCHITECTURE ON THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS.

ACTION 7: MASSIVELY INCREASE CLIMATE FINANCE, WHILE ENSURING ADDITIONALITY

- Consolidate and increase climate financing, align it with the Paris targets and better coordinate among remaining climate funds.

- Multilateral development banks and donors to assess and report on whether climate finance is additional to development assistance.

- Scale up adaptation financing to 50 per cent of total climate finance, and massively scale up grant finance.

- Quickly operationalize the loss and damage fund with new source of funding.

Disperse climate mitigation funds must be consolidated and rationalized to create mechanisms for climate mitigation financing at scale, with financing modalities and governance structures that ensure equitable governance and fair burden-sharing, while incorporating a gender-responsive, human rights-based approach. This includes replenishing the Green Climate Fund as the primary climate finance vehicle and ensuring greater coordination and coherence between funds, with better-defined linkages to other institutions. Dedicated climate funds10Akin to the proposal from the Bridgetown Agenda for the Reform of the Global Financial Architecture for the creation of a new mechanism backed by SDRs to accelerate investment in the low-carbon transition and resilience could be partially capitalized by SDRs, building on the recent experience with the IMF Resilience and Sustainability Trust.

Donors already report their climate finance under the enhanced transparency framework of the Paris Agreement. While there is of course overlap between development finance and climate finance, there are also differences, especially when financing climate mitigation. The international community should develop a mechanism to better account for climate finance to ensure additionality, such as developing a simple formula to estimate the additional global public goods expenditure. For example, for new energy investment, the cost of a clean investment could be compared with the estimated cost of a high-car- bon-emitting investment, with the difference being additional finance for global public goods.

To align climate finance with the needs of developing economies, and in line with the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, the international community needs to significantly scale up financing for adaptation, resilience and loss and damage – as well as for financing mitigation as a global public good – including scaled-up grant financing.

The loss and damage fund should be operationalized as quickly as possible. Loss and damage financing should be automatically triggered and forward-looking so that reconstruction is resilient.

ACTION 8: MORE EFFECTIVELY USE THE SYSTEM OF DEVELOPMENT BANKS TO INCREASE LENDING AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOAL IMPACT

- Set up a joint insurance or reinsurance fund to manage risk more effectively across the system of multilateral development banks.

- Increase collaboration across the system, in terms of co-financing, capacity-building and knowledge-sharing.

To fully maximize the balance sheets of multilateral development banks, the international system should better manage risks across the entire multilateral development bank system, for example through co-financing and diversification of regional risks at the global level. First, multilateral development banks should step up their cooperation between themselves through co-financing, as well as knowledge-sharing. Multilateral development banks should also work more closely with the broader public development bank system, including through on-lending and capacity support for national and subnational development banks, while benefiting from their local knowledge.

Second, to allow for greater lending without lowering their credit ratings, multilateral development banks should set up insurance or reinsurance funds to better manage risks across the system through diversification, including for:

- (a) risks from regional climate related disasters; and

- (b) local currency risks.

ACTION 9: ENSURE THAT THE POOREST CAN CONTINUE TO BENEFIT FROM THE MULTILATERAL DEVELOPMENT BANK SYSTEM

- Donors should meet official development assistance commitments and channel grants through efficient multi-donor structures, and consider permanent international financing mechanisms for concessional finance.

- Donors should commit to the principle that commitments to the least developed countries and other low-income countries will continue to be met.

- Increase concessional resources, including International Development Association contributions.

- Systematically consider vulnerability in all its dimensions in allocation criteria, going beyond GDP and ad hoc exceptions.

Many countries are still in need of grants and deeply concessional borrowing. Replenishments for concessional financing arms of multilateral development banks must also be more generous to ensure that the poorest are not left behind.

Eligibility to and allocation of concessional lending should be updated to reflect today’s vulnerabilities, including climate vulnerabilities, rather than just income and an assessment by the international financial institutions of the quality of a country’s policies and institutional arrangements. The special needs of conflict-affected countries also need to be addressed, which may require different operational mechanisms, such as considering the use of local implementing partners, and less risk aversion. Meeting the official development assistance commitments of donor countries can be achieved through higher commitments to concessional arms and funds of multilateral development banks, which should align behind country-owned and Sustainable Development Goal-focused plans as described in action 6. In addition, the international community should create permanent international financing mechanisms for concessional finance that guarantee a significant stream of resources for those with the greatest needs. Levies on transborder activities such as shipping, aviation, fossil fuel trade, and international financial transactions are natural candidates for creating such permanent mechanisms. Such levies should be designed for compatibility with efforts to disincentivize activities that harm developing countries’ economies, people, and the global environment.

Strengthen the global financial safety net and provide liquidity to countries in need

THE CASE FOR REFORM

The global financial safety net has grown in volume since the 2008 world financial and economic crisis but has remained relatively steady since 2012. With IMF at its centre, the global financial safety net also includes regional financing arrangements, bilateral swap arrangements and countries’ own foreign exchange reserves. Despite the multilayered nature of the global financial safety net, access is uneven.

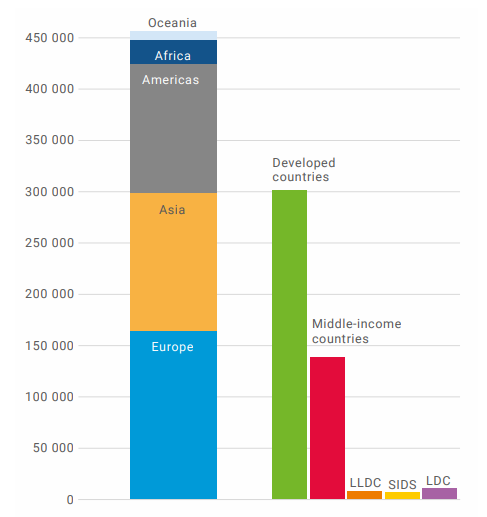

The new allocation of SDRs in August 2021 helped to bridge some of the gaps in the safety net. However, the mechanism for allocating SDRs in proportion to countries’ quota shares in IMF meant that developing countries received only about one third of the 2021 allocation, with the most vulnerable countries receiving much less (see figure IV). While both G7 and G20 have called for a voluntary rechannelling of $100 billion worth of unused SDRs, a fraction of that number has actually been rechannelled, with about $30 billion made available to IMF as at the end of January 2023.11As at the end of January 2023, IMF had 3.85 billion SDRs available from new note purchase agreements for the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust and 18.9 billion SDRs in contributions and borrowing agreements for the Resilience and Sustainability Trust.

FIGURE IV

SIZE OF SDR ALLOCATION, BY REGION AND COUNTRY GROUP, 2021

(Millions of SDRs)

Source: Calculations by the Department of Economic and Social Affairs based on IMF data.

Abbreviations: LLDC, Landlocked developing countries; SIDS, small island developing States; LDC, least developed countries.

By agreement at IMF, SDRs are intended to be the principal reserve asset in the international monetary system. However, they have never achieved that purpose, in part because of the unwillingness of countries to contemplate the regular issuance of SDRs and in part because the private sector has no interest in instruments denominated in SDRs.

The initial impact of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on capital flows confirmed the effectiveness of capital flow management. Those countries using capital flow management experienced relatively lower financing costs and exchange rate volatility and were, on average, better able to retain access to external financing. In the IMF institutional view on capital flows, the potential role of capital flow management and macroprudential measures is recognized. However, in the OECD Code of Liberalization of Capital Movements, as in many bilateral trade and investment treaties, full liberalization is still called for, reflecting the incoherence in the international system.

ACTION 10: STRENGTHEN LIQUIDITY PROVISION AND WIDEN THE FINANCIAL SAFETY NET

- Revamp the role and use of SDRs. This includes more automated SDR issuance in a countercyclical manner or in response to shocks, with allocations based on need.

- Make IMF lending more flexible, with fewer conditionalities and access limits and the removal of surcharges; borrowing limits should be based on needs to combat crises, rather than on quota multiples.

- Set up a multilateral currency swap facility.

- Strengthen regional financial arrangements.

To combat crises effectively, SDRs should be issued quickly at the start of financial crises or other shocks. In 2008–2009, it took 11 months after the onset of full-scale financial crises to agree on SDR issuance, while in 2020–2021, it took 17 months. Instead, SDR issuance should be subject to greater automaticity. Agreeing to triggers that automatically generate a recommendation on SDR issuance when conditions are met could help to prevent political delays. A new allocation formula will allow SDR issuance to be targeted to countries that truly need liquidity, including limited issuance to only those countries facing disasters or other shocks.

The overall size of IMF should be larger, and by explicitly separating voting rights from contributions (see action 1), members can move away from bilateral borrowing arrangements and towards full multilateral funding of the Fund. An initial boost to the Fund’s resources could be achieved by selling its gold valued at historical cost, which could generate over $175 billion in realized gains. The Fund should also remove the use of multiples of quota as guides for borrowing limits and end the use of surcharges, which can be counterproductive.

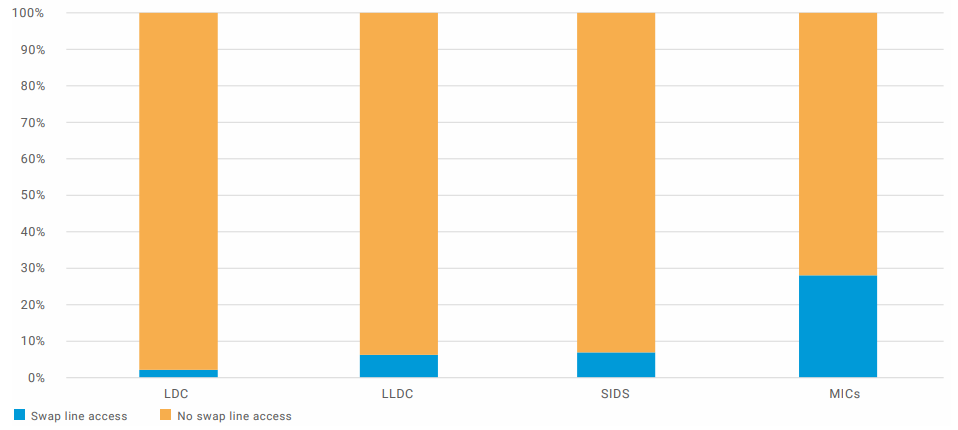

The most effective instruments for crisis management in the past 15 years have been central bank swap lines. They have provided urgent liquidity at almost no cost. They have the advantage of not only providing liquidity but also calming market fears, yet few developing countries have access to bilateral swap lines (see figure V). These can contribute to efforts to loosen access limits, as IMF or other institutions can have large volumes of resources in swap-like instruments with access unlinked to voting rights at IMF. Multilateral currency swaps would be particularly relevant for addressing exogenous shocks.

FIGURE Va

BILATERAL SWAP LINE NETWORKS, 2022

(Scaled by volume)

Source: Department of Economic and Social Affairs based on IMF and the Global Financial Safety Net Tracker.

Note: Colour-coded as follows: United States of America, green; China, red; euro area, orange; Japan, yellow. Swap lines between the aforementioned major central banks are blue. The swap lines between all other countries are grey. The size of each bubble represents the total amount of swap lines in United States dollar terms. Line thickness is scaled by the volume of the bilateral swap line – unlimited bilateral swap lines are set at maximum thickness.

Abbreviation: SAR, Special Administrative Region.

FIGURE Vb

ACCESS TO BILATERAL SWAP LINES, BY COUNTRY GROUPS, 2021

(Percentage)

Source: Calculations by the Department of Economic and Social Affairs based on Perks and others, “Evolution of bilateral swap lines”, IMF Working Paper No. 2021/210 (IMF, 2021); central bank websites; and IMF staff estimates.

Abbreviations: LDC, least developed countries; LLDC, landlocked developing countries; SIDS, small island developing States; MICs, middle-income countries.

Few countries turned to regional arrangements in 2020 at the time of the COVID-19 shock, in part because the amount of liquidity in most of the facilities is low and the conditions for access are sometimes considered onerous. Especially problematic is linking access to the regional safety net with the existence of an IMF programme, which negates the purpose of having a multilayered safety net. While the regional and global layers of the safety net should coordinate, formal delinking from IMF programme requirements and expanded resource volumes can ensure that this layer functions more effectively.

ACTION 11: ADDRESS CAPITAL MARKET VOLATILITY

- Strengthen macroeconomic coordination.

- Developing countries have access to the full capital account management toolbox.

- Source countries of capital flows should play an active role in reducing volatility.

International coordination and transparent for- ward guidance on monetary policy decisions in source countries for capital flows are critical to reducing negative spillovers. The G20 Framework Working Group was meant to strengthen macroeconomic policy coordination across G20 countries but has not been effective. Such coordination could be elevated to the meeting of finance ministers and central bank governors. IMF has been tasked with preparing a report on how the actions of source countries will affect developing countries, with recommendations to mitigate the negative effects.

Countries should further coordinate policy interventions with destination countries and relevant international standard-setting bodies to prevent international spillovers. This coordination of policy intervention should take place through an inclusive institutional body, with representation from all countries, for example a reformed IMF board and a biennial summit hosted at the United Nations.

On the part of countries, policymakers should draw on the full range of tools – monetary policies, exchange rate policies, macroprudential measures and capital flow management measures, among others – at their disposal to soften the impacts of volatile international capital flows. Capital flow management policies can incentivize long-term investment and still allow capital-constrained countries to reap the benefits of tapping foreign pools of capital. The availability of longer-term finance from multilateral development banks and improved debt restructuring architecture could also contribute to reducing market risk perceptions.

Reset the rules for the financial system to promote stability with sustainability

THE CASE FOR REFORM

Recent banking failures have highlighted gaps in financial regulatory systems, which have not kept pace with new technologies, through which information moves quickly and large financial transactions can take place instantaneously. The Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2022 warned that risks due to maturity mismatches and leverage, which were inherent to the financial system, had intensified during the long period of low interest rates and would likely materialize with sharp increases in rates. Prior to the recent bank failures, however, much of the analysis focused on risks in the non-bank financial sector, including in financial technology (fintech) and large technology companies in finance, where some institutions remain subject to less financial regulation and risks remain high.

There is also a need to address long-standing short-termism and volatility in financial markets, as well as to fast-track and strengthen efforts to align financial markets with the Sustainable Development Goals. Existing prudential regulatory frameworks risk slowing the transition to achievement of the Goals. Ultimately, stability and sustainability should be mutually reinforcing: stable markets encourage greater investment, while long-term investment in sustainability can play a stabilizing, countercyclical role.

There is considerable ongoing work on reporting on environmental, social and governance impacts by businesses and emerging work on incentivizing “peace-positive” investments. Sustainability disclosure is most advanced with respect to climate, with several jurisdictions beginning to enforce mandatory climate-related risk disclosures. The International Sustainability Standards Board under the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation is working to create a global baseline reporting standard, with the goal of publishing final standards by early 2023. These efforts are a good start but will be focused on the financial materiality of climate risks and not the impact of business on climate change and other sustainability factors. So far, there has been little agreement about how financial institutions should adapt their exposure in the light of these risks and impacts.

While there are international frameworks for financial integrity, there remain large volumes of resources illicitly created and illicitly moved through regulated and unregulated financial institutions. Too many loopholes remain, owing in part to the insufficient implementation of standards, but also to ineffective rules.

ACTION 12: STRENGTHEN REGULATION AND SUPERVISION OF BANK AND NON-BANK FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS TO BETTER MANAGE RISKS AND REIN IN EXCESSIVE LEVERAGE

- Regulate according to the principle of “same activity, same risk, same rules” to address financial stability and integrity risks from both bank and non-bank financial institutions.

- Address short-term incentives through tax incentives, incentive-based compensation, and the creation of long-term indices and credit ratings.

The principle of “same activity, same risk, same rules” implies greater regulation of non-bank financial intermediation that performs the economic function of banks, in addition to the market conduct regulations that are currently in place. The international community should advance balanced and comprehensive regulatory standards to cover new digitalized financial instruments to safeguard financial stability and integrity, while encouraging inclusive digitalization.

However, merely extending existing regulatory standards to institutions not covered would not solve the fundamental challenges that the world faces. International standard-setting bodies should develop guidelines for additional measures to reduce leverage and prevent excessive financialization of the world’s economies. This would include tax incentives to favour long-term equity investments, using transaction taxes (e.g. stamp duties on equity transactions) to discourage short-termism and placing regulatory limits on leverage for a wider set of institutions. To prevent competitive pressures from undermining these measures, they should, to the extent possible, be developed according to international standards and implemented internationally in a coordinated fashion.

After the 2008 financial crisis, there were nascent efforts to create deferrals and clawbacks on incentive-based compensation arrangements for banks and other financial industry staff, but these rules were never finalized or implemented across jurisdictions. Similarly, corporate governance should tie business leaders’ and management’s compensation to long-term performance and sustainability factors. In addition, the development of long-term indices and long-term credit ratings can help to benchmark investing with longer-term horizons.

ACTION 13: MAKE BUSINESSES MORE SUSTAINABLE AND REDUCE GREENWASHING

- Strengthen and mandate company sustainability disclosure and compliance with the Guiding Principles on Human Rights and Business.

- Make “sustainable” investing more credible, including by fixing sustainability ratings.

- Update market regulations, standards and practices to place the Sustainable Development Goals, and especially climate action, at the heart of the operation of markets and economies.

- Require clear Sustainable Development Goal-oriented transition plans from each institution within the international financial architecture.

- Design policy and regulatory frameworks to create and enforce direct links between profitability and sustainability.

Reporting requirements for large corporates, including financial institutions, need to include a common set of sustainable metrics regardless of their materiality impact, addressing the impact of businesses and financial institutions on the climate and other social and environmental issues. Investment advisers should be required to ask their clients about their sustainability preferences along with other information that they already request; and minimum standards are needed for investment products to be marketed as sustainable.

Updating market regulations, standards and practices to incorporate the Sustainable Development Goals and climate risks, as well as the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, would change market incentives. The requirement for transition plans would include the multilateral development banks, as well as regulators and standard setters and the financial institutions within their purview. Regulators and supervisors need to use the sustainable metrics to regularly assess whether financial systems and institutions are climate resilient.

However, the financial sector alone cannot change the economy. Policies should establish robust links between profitability and sustainability using appropriate sanctions and incentives to ensure that externalities, both negative and positive, are appropriately reflected in prices. This can be done with fiscal tools, such as carbon pricing, fossil fuel taxes or other environmental taxes, or through direct regulations to prevent harmful activities, with fines and penalties larger than the potential profit. To effectively meet commitments to combat climate change while addressing equity and political economy considerations, countries will likely need to use a combination of tools, including taxes, subsidies, market mechanisms and regulations, while providing targeted support to the most vulnerable.

ACTION 14: STRENGTHEN GLOBAL FINANCIAL INTEGRITY STANDARDS

- Integrate financial integrity into financial reform measures and systems.

- Create global standards for holding professionals accountable for the illicit financial flows that they facilitate.

Comprehensive measures towards financial integrity need to be a cross-cutting pillar of any reform of the international financial architecture. Strong transparency, governance and accountability measures are essential. Loopholes need to be closed and measures agreed upon to ensure that there are no secrecy jurisdictions to provide safe havens for illicit financial flows and the proceeds of crime.

Professionals can act as enablers in hiding income and assets and laundering the proceeds of crime. These enablers of tax avoidance, tax evasion and other types of illicit financial flows have escaped effective action for too long. To prevent aggressive tax planning practices, enablers need to be regulated. New international norms need to be created to prevent regulatory arbitrage. At the national level, these norms need to be translated into appropriate regulation and supervision of all professions that might enable money-laundering, tax avoidance and evasion and other illicit financial flows, with proportionate transitional arrangements for countries with low capacity and not posing large risks to global financial integrity. At the national level, sanctions will be needed, but safeguards are essential to prevent abuse of these rules for domestic political purposes rather than for safeguarding financial integrity. This could include the creation of new regulations or improved oversight of existing rules.

Redesign the global tax architecture for equitable and inclusive sustainable development

THE CASE FOR REFORM

Domestic tax systems are foundational to the social contract in which taxpayers contribute to society and Governments provide valuable public goods and services. At a fundamental level, taxation finances and supports the functioning of the State; yet in an increasingly globalized and digitalized economic system, effective international tax cooperation is essential to guarantee the functioning of domestic tax systems. There is widespread agreement that the current international tax cooperation architecture needs to be strengthened to combat tax avoidance and evasion and other illicit financial flows, which drain much-needed resources from countries, which could otherwise be used for investments in sustainable development.

Multinational enterprises exploit gaps and mismatches in tax rules to artificially shift profits to low- or no-tax locations and losses to high-tax jurisdictions to avoid or evade taxation. There is a general mismatch between the resources that many multinational enterprises have to engage in tax planning, compared with the resources of the Governments to enforce tax rules. Moreover, the current tax architecture is built on taxation principles that are not well adapted to digital business models. In addition, the ultra-wealthy use the lack of transparency on both asset ownership and control of legal entities (e.g. shell companies) to hide their wealth and capital gains from taxation.

Most multilateral tax agreements have been developed only recently and in forums without universal participation. Norms are being developed in forums in which countries with the greatest needs do not participate, or in forums in which they do participate but without sufficient inclusivity. The result is that countries with the greatest needs are not benefiting from the development of new international tax norms. This deficiency limits the potential effectiveness of tax norms and the tax system over time.

Progress in improving tax transparency is emblematic of this challenge. The terms of the governing instruments and their high confidentiality demands effectively exclude most developing countries from accessing information that could help them to more effectively tax high-net-worth residents or multinational enterprises operating in their countries.

The slow progress in responding to calls by developing countries for inclusivity in tax cooperation frameworks has damaged faith in multilateral- ism and the promise of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, but it has also led to renewed calls for a fair and effective international tax system for sustainable development that reflects the concerns and capacities of all countries.

ACTION 15: STRENGTHEN GLOBAL TAX NORMS TO ADDRESS DIGITALIZATION AND GLOBALIZATION THROUGH AN INCLUSIVE PROCESS, IN WAYS THAT MEET THE NEEDS AND CAPACITIES OF DEVELOPING COUNTRIES AND OTHER STAKEHOLDERS

- Explore options to make international tax cooperation fully inclusive and more effective.

- Simplify global tax rules to benefit underresourced developing country tax administrations.

General Assembly resolution 77/244 on the promotion of inclusive and effective international tax cooperation at the United Nations, adopted in 2022, has initiated intergovernmental discussions on options to strengthen the inclusiveness and effectiveness of international tax cooperation, including the possibility of developing an international tax cooperation framework or instrument that is developed and agreed upon through a United Nations intergovernmental process, taking into full consideration existing international and multilateral arrangements. To better equip developing countries in their fight against tax base erosion and profit shifting, easily administered solutions need to be developed. Developing countries prefer simple approaches, such as digital services taxes or withholding taxes, over more complex strategies. While not easy to achieve, such simplification of tax rules benefits the effectiveness and sustainability of the international tax system. This benefit accrues to all stakeholders in tax systems. The Secretary-General will present options for the consideration of Member States in his report to be submitted pursuant to resolution 77/244.

ACTION 16: IMPROVE PILLAR TWO OF THE PROPOSAL BY THE OECD/G20 INCLUSIVE FRAMEWORK ON BASE EROSION AND PROFIT SHIFTING TO REDUCE WASTEFUL TAX INCENTIVES, WHILE BETTER INCENTIVIZING TAXATION IN SOURCE COUNTRIES

- Significantly increase the global minimum corporate income tax rate to be close to the statutory tax rates in most developing countries and give preference to source country taxation.

The proposal for a minimum corporate income tax rate is welcome, but the minimum is likely to become a maximum due to tax competition. Developing countries have repeatedly called for setting the global minimum tax rate at a significantly higher level that is more in line with statutory tax rates prevailing in their countries. The agreement needs to give first priority to source country taxation and include stronger rules to eliminate tax base erosion.

ACTION 17: CREATE GLOBAL TAX TRANSPARENCY AND INFORMATION-SHARING FRAMEWORKS THAT BENEFIT ALL COUNTRIES

- Create non-reciprocal tax information exchange mechanisms to benefit developing countries.

- Publish beneficial ownership information for all legal vehicles.